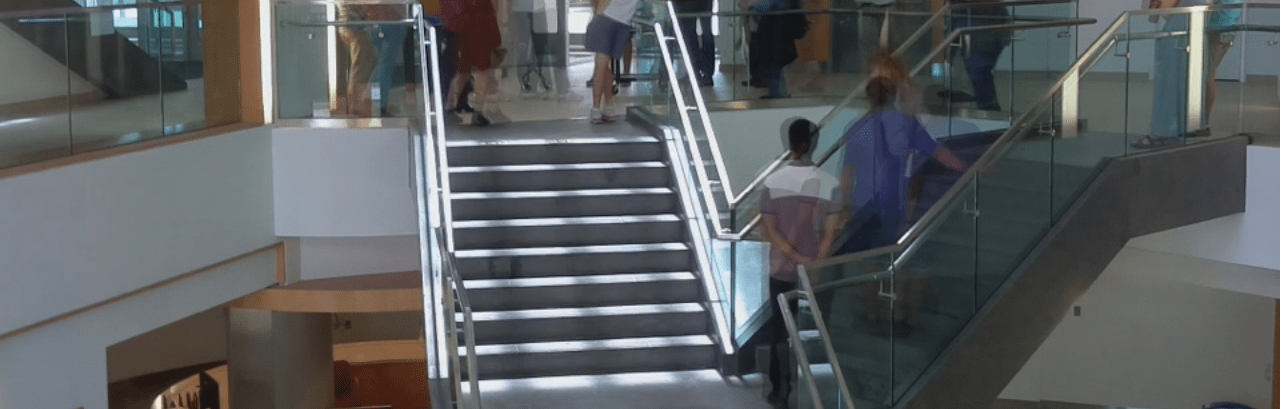

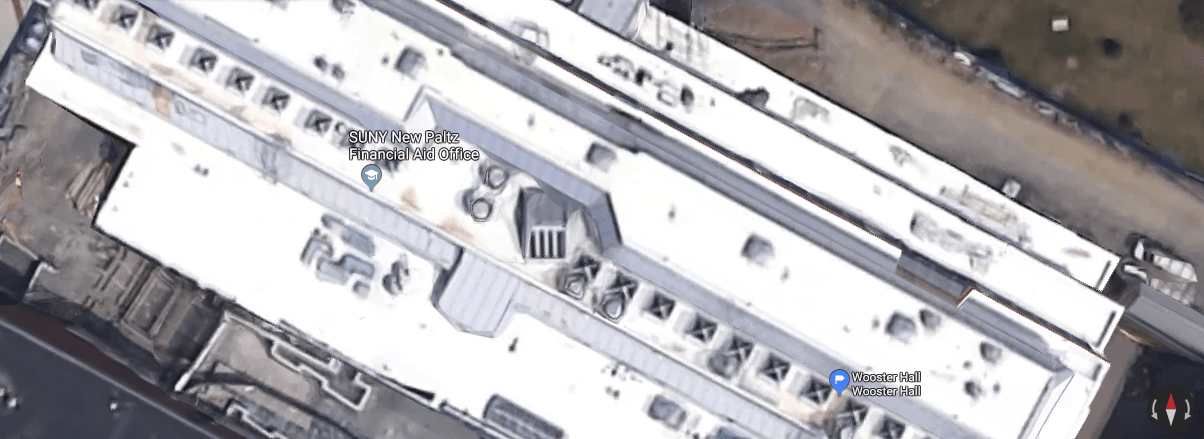

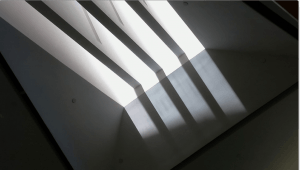

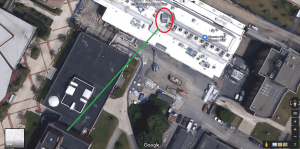

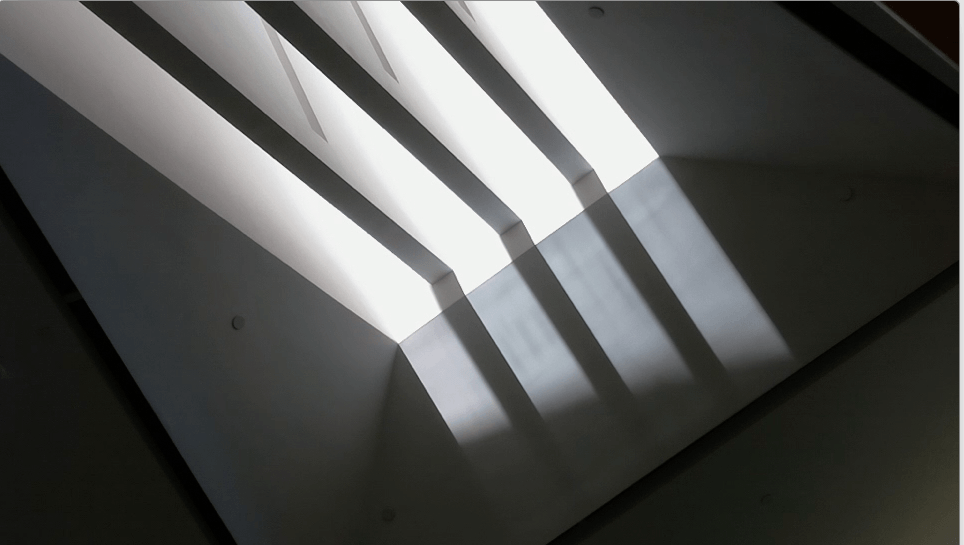

Wooster Hall on the SUNY New Paltz campus was completely remodeled recently, and a neat new feature is an alignment of the skylight over the main stairway such that the bottom of the stairs is lit up at exactly solar noon on the Equinox (both spring and fall).

This spring when I observed this I was inspired, on the fly, to create a time-lapse video of the event, using just my hand-held phone. You can see the video here.

Making the time-lapse video from the still images was a fun little exercise in Python programming, and the purpose of this post is to show how I did it. I need to start out by saying that this is all really crude compared to what one can do now with time-lapse photography, but it was what I was able to do with little background or training, so I wanted to at least record what I learned.

One of the challenges to deal with is that the images were not captured at regular intervals, since I was taking them by hand with my phone. I tried to space them out about every minute, but sometimes it took longer (like when someone was in the way) and sometimes I took them more frequently (as we got closer to solar noon). Even so, I wanted to make the video flow as smoothly as possible by adjusting the time between frames accordingly. That lead me to choose to make an animated GIF instead of some other format, because an Animated GIF can have different time delays for different images, whereas most video has a uniform spacing between frames.

My previous experience making an animated GIF was using the command line convert tool from Image Magick, but even that assumes a standard frame rate and does not make it easy to change the delays individually for different frames. Still, I knew that the time of each image was recorded in the JPG file, so in principle I could use that to adjust the time between frames, if I read that information programatically. That lead me to choose to write a Python script to do the job. And then looking at what was available in Python, I chose to use PIL, the Python Image Library.

The way it works, overall, is that you read in all the images into a list, then save the first image as a GIF, and at the same time tell it to append all the other images, with an array of different time durations to show each image. For animated GIFs the time to show each frame is in hundredths of a second, so I simply scale down the time interval between when the pictures were taken to an appropriate amount in hundredths of a second.

I also needed to do some processing for each image, before it was added to the animation.

Because I held the phone horizontally (landscape) but the JPG files default to “up” being portrait mode, I had to rotate each image by 90 degrees. I also wanted to scale down the size of the image to make a smaller animated GIF appropriate for a web page, rather than a full sized video.

To get started I imported PIL and set up some empty arrays to hold the images, the durations (time between frames), and the names of the original image files.

from PIL import Image

images = []

durations = []

prev_time = datetime.now()

The current time is saved in prev_time to start the process of computing the time between successive photos. At this point I just needed a value which is both a ‘dateime’ object and somehow signals that it’s not a part of the sequence of times, which this does by being so much later than the first image.

Before reading in images, I needed an ordered list of the file names. The file names are simply IMG_2921.JPG up to IMG_2821.JPG, in order. I used the os module and made sure that the list was properly sorted:

import os

# Get a list of .JPG files

filenames = []

for file in os.listdir('.'):

name, ext = os.path.splitext(file)

# Only files, only .JPG files

if os.path.isfile(file) and ext == ".JPG":

filenames.append(file)

print "Found ", len(N), "image files. "

filenames.sort()

With this list I was able to use PIL to read in each image file, rotate the image, resize the image, and then save the image in a list:

for file in filenames:

img = Image.open(file)

rotimg = img.rotate(-90,expand=1)

newsize = ( int(rotimg.size[0]/scale), int(rotimg.size[1]/scale) )

frame = rotimg.resize(newsize)

images.append(frame)

I set scale to 5.0 to reduce the size to 1/5 the original.

After saving each frame in the animation, I get the timestamp from the EXIF data in the original image, which just happens to be element 36867 of the EXIF property array. (You can look this up — I certainly had to). From this I computed the time duration for each frame, in hundredths of a second:

# Duration of frame comes from actual time difference between photos

exif = img._getexif() # JPEG photo metadata (EXIF)

datestamp = exif[36867] # date/time the photo was taken

img_time = datetime.strptime(datestamp,"%Y:%m:%d %H:%M:%S") # parse datestamp

deltat = img_time - prev_time # difference as "timedelta" objects

dt = deltat.total_seconds() # difference in seconds (or fraction of)

if dt < 0: # ignore the first one, it's bogus

durations.append(dt*100.0/speedup) # GIF duration is in 100ths of second

prev_time = img_time # Save timestamp for next iteration

In Python, differences between ‘datetime’ objects are ‘timedelta’ objects and then we convert that to a float value in seconds, called dt, and rescale that to hundredths of a second. The scale factor speedup was set to a value of 30.0 to get a reasonable speed for the animation.

Notice that the duration of the frame is not saved for the first frame. That means that for the 99 images in the collection, there are only 98 durations (and of course they are all different). This turns out to be almost what is needed for the next step, putting all the frames together into the animation.

After this loop over all frames, the rotated and scaled images are in the list named images, the duration for each frame is in the list durations, and it’s time to put them all together. The way this is done is to write one frame image, and then tell PIL to append to it the list of the other images, with the list of durations.

print "Writing the movie..."

first = images.pop(0)

durations.append(100) # pause 1 second at end of loop

print len(images), len(durations)

first.save("WoosterMovie.gif",save_all=True,

append_images=images,duration=durations,loop=47)

With 99 images in the list, the first is put into the variable first (and removed from the images list, which now has 98 elements. Meanwhile, I had to add another element to the end of the durations list, so now there are 99 durations. That makes some sense, because there are 99 images overall, but the mis-match between the length of the images list and the durations list was very confusing to me, and is probably the most important reason for writing this posting. Which is why I even printed the lengths to verify them when I finally got it figured out. But as you can see from the comment, it also means I could control the length of the pause at the end of the animation before it repeated. Also as you can see, you “save” the first image, and then pass the other images and durations as parameters, which seemed kinda weird at first, but that’s how the API works, so that’s how you do it. Hopefully this working example is useful to someone else, or at least to me in the future when I forget all this.

References