Threadneedle Street is a street in which the characters of Doyle’s short story, “The Man with the Twisted Lip,” part of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, refer to as the City. The story starts off with Watson on a mission to retrieve a friend from the opium den on Swandam Lane, and while at the opium den, runs into Sherlock Holmes, who is there investigating the potential murder of Mr. Neville St. Clair. The prime suspect for St. Clair’s murder is the poor beggar, Hugh Boone, who lives in the apartment above the opium den. Hugh Boone is described as a decrepit beggar who, “though in order to avoid the police regulations he pretends to a small trade in wax vestas. Some little distance down Threadneedle Street, upon the left-hand side, there is, as you may have remarked, a small angle in the wall. Here it is that this creature takes his daily seat…” (7). This description, given by Watson is important in not only figuring out the mystery of the story, but also what Threadneedle Street was like during the early nineteen hundreds.

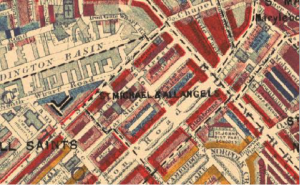

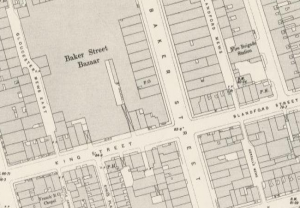

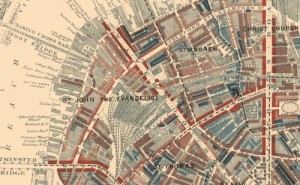

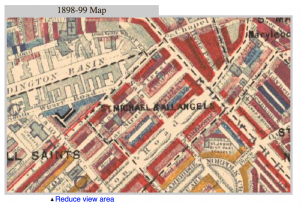

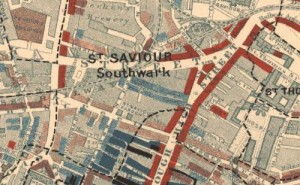

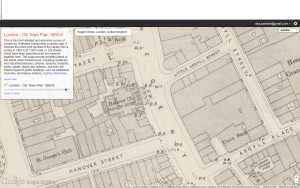

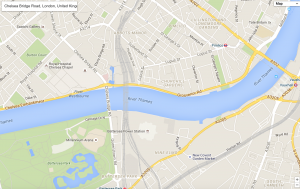

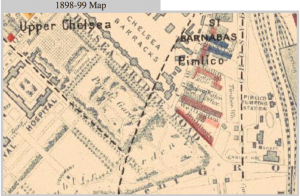

Threatneedle Street is the street that runs parallel to Cornhill and perpendicular to Bishopgate Street, forming a triangle north of the Thames River. The triangle these three streets form is the center of business in London, as the Royal Exchange and Bank of London are located between the three streets (Victorian Google Maps). The Royal Exchange, started by Mr. Edward Moxhay in 1830, under the name The Hall of Commerce, as an area for merchants to gather and trade without the threat of larger, monopolizing businesses (Thornbury). Due to it being the home of the Royal Exchange, Threadneedle Street is important to understanding the context of Doyle’s story. Threadneedle Street is where Hugh Boone “works,” because even for a beggar there is more opportunity in the heart of the city, as opposed to where he lives, which is in the opportunity-less slums. Doyle’s inclusion of the contrast between a beggar’s opportunity in the City and by the opium dens suggests how it is inevitable, even if one needs to be a beggar, to be a part of modernized London.

Threadneedle Street is also the home of the Bank of London, the Jewish synagogue-turned-school-turned-Church-turned-bank (Thornbury). The Bank of London is not only significant to this location in real life as well as the plotline of “The Man with the Twisted Lip,” due to its obvious financial role, but also due to the vast history the establishment holds. The Bank’s history reinforces how diverse and important of an exchange place Threadneedle must have been especially during the eighteenth and nineteenth century. Before the building was an active part of the financial-driven part of London, it went through many different stages of being social and institutional centers, thus proving the importance and versatility of this area; no wonder why Boone decided to beg there. Not only is the Bank of London located on Threadneedle, but also the street is lined with dozens of other smaller banks and exchanges (Victorian Google Maps).

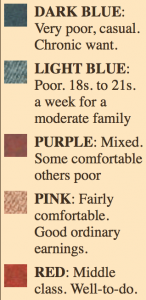

In terms of theme, Threadneedle Street is significant in displaying the layered contrasts between the working class of London, the beggars of London, and the “CEOs” of London, which allows readers to understand and imagine 1850-1900’s London with more clarity. The City, which is how the characters of the story refer to the Threadneedle district, is a melting pot of all the different prototypes that make up the capitalist, modern system in which London has developed due to the introduction of industrialization. Due to the competition introduced by industrialization, small merchants such as Mr. Moxhay found it integral to create a space in which more fair competition can exist. In doing so, the financial world created itself around the merchants’ power to congregate and establish grounds and due to the district’s financial boom, others, such as beggars, also establish themselves and function around the systems established. This multi-layered development of what Threadneedle Street represents is the beginning of London’s full-fledged transformation into the modern City.

Works Cited:

Doyle, Sir Anthony Conan. “Adventure 6: The Man with the Twisted Lip.” The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. London: George Newnes Ltd, 1892. Florida Center for Instructional Technology, College of Education, University of South Florida. 2015. Oct 18 2015.

Thornbury, Walter. “Threadneedle Street.” Old and New London. Vol. 1. London: Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1878. 531-544. Oct 18 2015.

“London – OS Town Plan 1893-6.” Google Maps Engine. Google-Imagery TerraMetrics, 2015. Oct 18 2015.