Russell & Allen appears in Amy Levy’s The Romance of a Shop on page 79, as an elite dressmaker and supply shop where Constance, as a newly engaged women, tries on a ball dress. (pg. 79)

Unfortunately, while looking for more information on Russell & Allen’s shop, including what the storefront may have looked like, I could find no surviving images, as it would appear the store disappeared sometime in the late 1890s to early 1900s. The most information I could find on the store came from the footnotes on page 79 of The Romance of a Shop: “Messrs. Russell and Allen, Old Bond Street, London, W.” was an exclusive dress designer and supplier shop, according to photographs on the website of the Victoria and Albert Museum.” (pg. 79)

However, I did manage to find photos of preserved clothing that were made and sold via Russell & Allen’s shop, courtesy of the Victoria & Albert museum website.

It’s clear to see that Russell & Allen made many high quality outfits, and it’s interesting that Amy Levy chose to include Constance’s engagement with the fact that she is trying a dress there. Perhaps she meant to express that Constance would only spend the money required for a Russell & Allen dress for an extremely special occasion, such as an engagement.

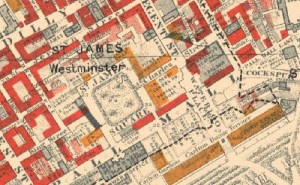

According to the Charles Booth Poverty Map, Russell & Allen, located on Old Bond Street, was surrounded by middle-class and upper middle-class dwellings, which seems obvious since Russell & Allen was a very expensive store. Only the upper middle class could afford to shop there, or have custom-made outfits made there. Even today, Old Bond Street is home to many expensive stores housing designer artifacts, such as Gucci outfits, who supply goods to the British Royal Family.

The only crime I could find being committed in the vicinity of Russell & Allen was a case of fraud, in which the defendant was found guilty. A man by the name of Adolf Beck appears to have tried to trade stolen jewelry for forged checks, one of which was made out to Russell & Allen.

WORKS CITED

Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2, 10 December 2015), February 1896, trial of ADOLF BECK, Unlawfully (t18960224-277).

Booth, Charles. “Old Bond Street.” Charles Booth Online Archive. Web. 10 Dec. 2015.

“Bond Street.” Shops and Art Galleries in New Bond Street and Old Bond Street, London. Street Sensation, n.d. Web. 10 Dec. 2015. <http://www.streetsensation.co.uk/mayfair/bs_intro.htm>.