Threadneedle Street is mentioned in The Man with the Twisted Lip, where Neville St. Clair, disguised as Hugh Boone, performs his beggary. Boone sits, “Some little distance down Threadneedle Street, upon the left-hand side,” just outside the opium den (Doyle 5). This is where Mrs. St. Clair spots her husband flailing from a window. Before this interruption she walks skeptically, “glancing about in the hope of seeing a cab, as she did not like the neighbourhood in which she found herself” (Doyle 4). The story gives the impression that this was an impoverish and faulty area.

A historical account of Threadneedle St. recalls the area was occupied by “cripples on go-carts who haunted the neighbourhood” (Thornbury, “Threadneedle Street”). This alludes to Doyle’s story quite well considering St. Clair portrayed Boone as a cripple.

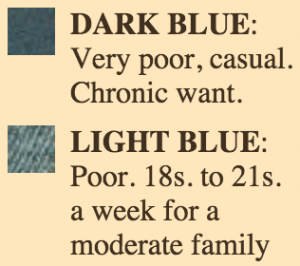

Taken from the “Charles Booth Online Archive,” the area surrounding Threadneedle Street was classified as poor. (See Poverty Classification Key.)

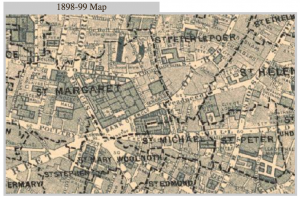

It’s hard to see clearly, but the street is located mid photo, above St. Michael. View the “Booth Archive” page, here.

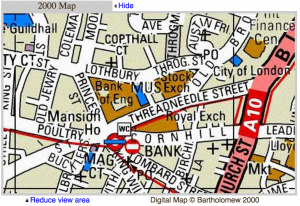

Here’s a better glimpse of Threadneedle Street from 2000.

Here’s a better glimpse of Threadneedle Street from 2000.

The crime and poverty as described in The Twisted Lip and the Poverty Classification (Booth Archive) of Threadneedle St. correspond well.

So, how much crime actually surrounded Threadneedle Street based off of the story in The Twisted Lip? Using “Old Bailey Online,” I was able to find multiple accounts of grand larceny, murder and theft in the Threadneedle St. area. From the Conviction of Henry Harrison, Mr. Harrison, escaped prisoner, hid for sometime in the home of a Mr. Garway. As it is mentioned, “He takes a Lodging at Mr. Garway’s in Threadneedle-street, on the twenty third day of December, and there he continued till about the first of January” (“Henry Harrison, Killing”). Mr. Harrison was a convicted murderer. Pretty profound!

A particular case involved several pieces of stolen clothing by a man named Joseph Johnson, carrying “the Goods of William Savage” from London’s Lombard Street to Threadneedle Street (“Joseph Johnson, Theft”). Other cases involved pickpocketing, and violent encounters. A constable was charged with Edward Lynch, where on “Threadneedle street, [the prisoner] drew a knife upon the prosecutor” and made attempts at the constable as well (“EDWARD LYNCH, Theft”).

Charles Rice, who had stolen innumerable goods, was spotted on Threadneedle Street. Once, by a man named Thomas Edwards who “was coming up Threadneedle-street, when [Rice] was in custody,” and another time by Alexander Barland who saw [Rice] heading towards the “Edinborough coffee-house” (“CHARLES RICE, Theft”).

Edinborough wasn’t the only coffee-house mentioned near Threadneedle St. From “British Histories” I learned of the “North and South American Coffee House (formerly situated in Threadneedle Street)” (Thornbury, “Threadneedle Street”). There was also the Baltic Coffee House, where merchants and brokers occupied their time. It was described as a “rendezvous of tallow, oil, hemp, and seed merchants” (Thornbury, “Threadneedle Street”).

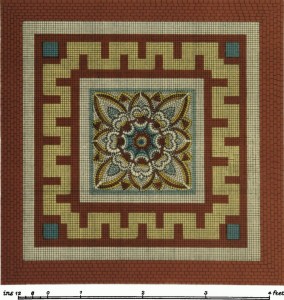

Threadneedle was also the site of the French Protestant Church where red pavement lined the streets. The findings of pavement are rather remarkable and exceptionally crafted (Thornbury, “Threadneedle Street”). It goes to show that Threadneedle St. was not solely defined by theft and poverty but the site of pleasant coffee-houses and decorated pavement.

The Threadneedle Street Pavements:

Works Cited

“Joseph Johnson, Theft, October 1720 (t17201012-3).” Old Bailey Proceedings Online. Web. 6 November 2015. <http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t17201012-3-defend38&div=t17201012-3#highlight>

“Henry Harrison, Killing, April 1692 (t16920406-1).” Old Bailey Proceedings Online. Web. 7 November 2015. <http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t16920406-1&div=t16920406-1&terms=+threadneedle%20+street%20#highlight>

“CHARLES RICE, Theft, September 1785 (t17850914-125).” Old Bailey Proceedings Online. Web. 7 November 2015. <http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t17850914-125&div=t17850914-125&terms=+threadneedle%20+street%20#highlight>

“EDWARD LYNCH, Theft, September 1776 (t17760911-34).” Old Bailey Proceedings Online. Web. 7 November 2015. <http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t17760911-34&div=t17760911-34&terms=+threadneedle%20+street%20#highlight>

Thornbury, Walter. “Threadneedle Street.” Old and New London: Volume 1. London: Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1878. 531-544. British History Online. Web. 7 November 2015. <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/old-new-london/vol1/pp531-544>

“Plate 50: Threadneedle Street, Pavements.” An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in London, Volume 3, Roman London. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1928. 50. British History Online. Web. 5 November 2015. <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/london/vol3/plate-50>