Here is our final project link:

http://hawksites.newpaltz.edu/raceandpoverty/

Jordon, Miranda, Jesse and Orly

Here is our final project link:

http://hawksites.newpaltz.edu/raceandpoverty/

Jordon, Miranda, Jesse and Orly

Sherlock holmes and Watson in the story The Blue Carbuncle walk through the streets of London on their way to the Alpha Inn to follow up a lead into the case of the stolen blue carbuncles. Harley Street is parallel to Baker street (see on OS map above), and not far so the route, they walked through in the story, makes sense. However, when following this route on the map it does not match up. Harley Street does not meet with Wigmore on the way to Holborn, as can be seen on the OS map of London from 1869-80 below.

In the story they walk from Harley Street to Wigmore Street which is possible only if they turn counter to their next destination Oxford Street towards Holborn. The point is that Conan Doyle wanted to include Harley and Wimpole streets in the story even if it doesn’t make sense for them to walk that way, especially when in a rush in a very cold night.

Harley Street is specified in the story as the doctors’ quarter. it was, and still is, regarded as the quarter of the best doctors:

Harley Street is also discussed in the story The Resident Patient:

Here again a Harley Street doctor is mentioned as an indication to a high quality care given to Sherlock Holmes.

The map in Charles Booth Poverty map shows that Harley street residents were from Upper-middle and Upper classes, Wealthy.

Baker Street residents, according to Booth Poverty Map are designated in red- middle class, Well-to-do . So Harley Street residents were considered of a higher class then those on Baker Street.

Walter Thornbury in his book Old and New London: Volume 2 supports the portrayal of Harley street: “The doctors now swarm in Cavendish Square, Harley Street, Wimpole Street….” referring to the migration of practitioners from Finsbury Park area to the Harley street area in mid 19th century. He continues: “When the doctors and surgeons thus swarmed in the Finsbury district, the City and its adjacent districts were largely inhabited by wealthy families, that have now also migrated westward, as their doctors naturally have.

Sherlock Holmes in his walks in upper class districts, and in him being treated by upper class doctors maybe positioned as a close member to the upper classes. In the British class based society this position might be necessary to shape Holmes’ character as respected and trusted.

Oldest Trees in the World

Fusion Table link

And the tables analyzing oldest trees by age, type, dead or alive and location:

Location of the Oldest Trees in the World

Location of the Oldest Trees in the World

My video essay is all done just click here

Love, war and church, three banal words whose meaning did not change with time. War is the same old war known to be in use from the 12th century: “Hostile contention by means of armed forces, carried on between nations, states, or rulers”

Love as we know it “A feeling or disposition of deep affection or fondness for someone” had, to my surprise, another meaning that was known during the 19th century. ” Any one of a set of transverse beams supporting the spits in a smokehouse for curing herring” . However in the books Google scans it is mostly about love between people or the love of god.

The last word church “A building for public Christian worship or rites such as baptism, marriage, etc” also kept its meaning.

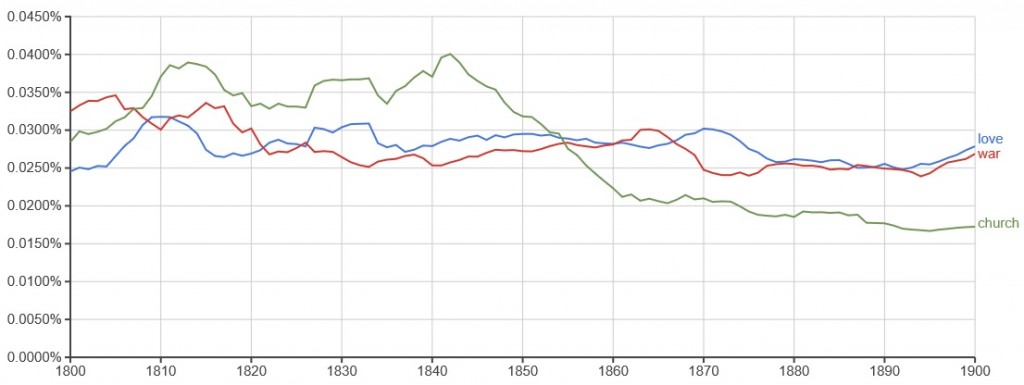

I chose to write about those three words for two reasons: the first is the high frequency of their use in books between the years 1800 to 1900 compare to other words I checked like art, science, culture, etc. And the second reason is the interesting relationship between the graph lines of the words love and war.

When war (in red) is high love (in blue) is low and vice versa. The first peak of the word war appears in 1805 at 0.03459977588%. 1805 is during the Napoleonic wars that lasted between the years 1803 and 1815. The second peak is indeed at the end of this wars 1815 at 0.0335997686%. At the same period the word love is at its low 0.0252718073% in 1803 and the second low in 1816. This interchanging relation is also happening in the 1870 when love is at its peak and war is low, historically this is just after the end of a few great wars that took place in Europe like the Crimean war that ended in 1856, the wars of the British Empire with other nations like Opium wars (ended in 1860) and the American civil war that ended in 1865. From 1877 until 1900 the two words are very close in frequency yet love is a little higher until the 20th century when the story changes completely , see the graph below .

The frequency of the word church behaves differently. It is very high, even higher than the words war and love words, until 1842 when it reaches its peak at 0.040051273380%. A steady descend is taking place from this peak in 1842 until 1900 that gets me to conclude that the interest in church was apparently at its highest in the early 1800 . Looking at some of the titles Google scanned from the 1840’s, Christianity is represented on its various offshoot (Anglican, Russian Protestant, etc.). At the end of the century the word church, again on its various offshoots, appears less. The frequency of the word descends from the above 0.040051273380% to the low 0.0167875362% in 1894, and keeps descending into the 21st century.

To find reader traces in a university library book seems impossible, even the old books from the 1800 are in such good and clean condition. Still, after leafing through some 20 and more books in the travel section (DA), I picked a small hand book for travelers, and in it there was a hand written note. The book is Baedeker’s Great Britain Handbook for Travellers , published in Leipzic (original spelling), Germany and in London, Great Britain in 1897. It’s a small red book written in almost microscopic letters and it contains colored maps, plans and panoramic illustrations of different places in Great Britain. It provides a great deal of information about the country using this tiny little font type.

The hand written note is placed around the book title, written in ink in an old fashion style. I couldn’t decipher the writing so Prof. Swafford was called for help and her reading was: “Paddington St, Leave for Wells at 1.20 (Bristol) 3.88. Leave Bristol for Yeaton + Wales 5.25 6.47″. It seems the note was maybe a preparation for a trip in England. To add to this assumption I also found a folded big colored map of (just) England that was placed in a special pocket in the Inside cover of the book.

The map is a little fragile so very gently I managed to open it without tearing and to my surprise an itinerary was marked on the map in dark ink .

The book was, after all, used as a travelers handbook despite its very clean state. Maybe the text wasn’t that useful, but the map definitely was.

Submitted to Book Traces : http://www.booktraces.org/book-submission-baedekers-great-brittain/

Sherlock Holmes Place exhibit is ready can be looked at in A Study in Holmsiana:

I included three items:

Baker Street 221b street façade

They all appear in the collection:

The Victorian age bright side was the industrial revolution with its great inventions and scientific progress, but this magnificent age had also a dark side to it a social dark side. George R. Sims in his chapter How the Poor Live, exposes one aspect of this dark side: deep poverty, a situation that forced the young members of families, the children, aged between six and ten to “work hard at dangerous trades for their living “. Girls work long hours for pennies in a ‘Bronzing factory’ using dangerous chemicals which caused fatal illnesses without taking any precaution and without getting any protection either from their bosses or families. Another example is of young boys sometimes age six or seven working in sawmills, again no precautions were taken resulting in fingers loss or worse even loss of hands to the machines. Lead poisoning was another fatal condition that those young children died of working in the lead industry and Lemonade bottling factories where bursting bottles maimed children who were doing the job.

The poorer the family the younger the kids who went to work. James Greenwood, in his book The Seven Curses of London from 1869, describes the stages that little boys went through from the age of seven to become a prestigious “errand boy” when they are ten. They worked from early morning till the late hour of the evening winter and summer alike to earn something. ‘Uncle Jonathan’ In his Walks In and Around London, from 1895, described them as the “children of the poor who have to earn their own living”. Not earning any money resulted usually in cruel beating or other cruelties at home. The jobs ‘Uncle Jonathan’ described are not these dangerous jobs that make the reader shiver but more of mundane little independent initiatives that render the kids transparent, unnoticeable. Those kids were to be found in markets, like Covent Garden in Uncle Jonathan’s story, where at about five or six o’clock in morning those kids showed up to buy their merchandise for the day, boys and girls alike: flower girls, Orange-girls, the little match-sellers, telegraph boys etc. Other kids worked as scavengers, collecting horse discharge from the dangerous bustling roads, risking their life for pennies.

I’m a visual art major on my second year, focusing on ceramics.