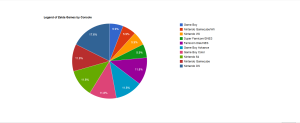

The development of police forces progressed drastically throughout the 19th century. This advancement in the police force made me curious as to whether or not police appeared as often as crime in english literature during the 19th century. The first two words I entered into Google NGram Viewer were crime and police.

Crime made a steady appearance in English literature throughout most of the 19th century, showing up much more often than police until about 1880. In 1880, police takes a huge turn and begins popping up a lot more while the appearance of crime decreases slightly. I googled “police in 1880” in an attempt to figure out what caused this spike in the appearance of police. One of the first web results revealed that there was a surge in gun crime in 1880, mainly in London. I also found that urban police departments in the 1880s were developing new methods to keep track of criminals and maintain records about them. Here, it became evident that the word police was beginning to come into English literature more often because surges in violence prompted police to develop more effective strategies in approaching crime and criminals.

I think that crime and police cross paths in 1893 on Google NGram Viewer because many cities developed (or were in the process of doing so) strong police forces after seeing their success in other cites. The growing popularity of police forces suggests that crime in 1893 English literature probably involved police.

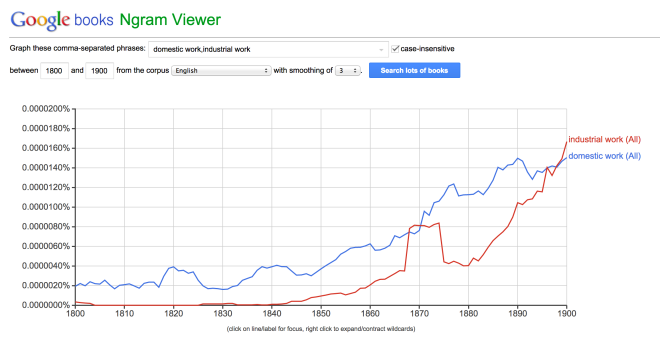

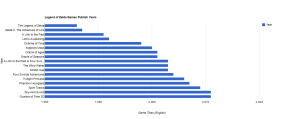

The next two phrases that I entered into Google NGram Viewer were domestic work and industrial work. I was curious to see if the change from the domestic industry to the factory/industrial industry was reflected onto the pages of books in English literature.

The graph processed by Google Ngram Viewer shows that industrial work was seldom mentioned in English literature until 1843. After researching industrial work in 1843, I found that between 1843 and 1848, women protested their wage decrease in textile mills (industrial work). Another prominent point on this graph is the period from 1866 to 1869, where the appearance of industrial work spikes and then crosses paths with domestic work. Perhaps the reason for the spike is the invention of dynamite in 1866, and tungsten steel in 1867. Both played an important role in the industrial revolution because dynamite allowed for the clearing of paths (to build on), and tungsten steel was used in new buildings. During such a pivotal period, people probably began writing more about the industrial revolution, which explains this spike in the appearance of industrial work.

In 1875 industrial work became less popular in English literature and then began to climb gradually in 1880. In 1890 we see a peak in the appearance of domestic work. This was when the National American Woman Suffrage Association was formed and the American Federation of Labor declared support for woman suffrage. Female voices were heard and women were able to discuss their desire to vote and to be viewed seriously outside of the domestic workforce. This movement may explain the peak in the appearance of domestic work in English literature.

Altogether, I found that Google NGram Viewer is an effective way of “distant reading.” It allows me to spot trends across many different works by looking at frequency words and phrases in literature. The only change I suggest on this site is the addition of axis titles.

Mary Dellas

Works Cited:

“Detection and the Police.” Detection and the Police. N.p., n.d. Web. 19 Oct. 2014.

“How Safe Was Victorian London?” How Safe Was Victorian London? Ed. Jacqueline Banerjee. N.p., 6 Feb. 2008. Web. 19 Oct. 2014.

“National Women’s History Museum.” Education & Resources. NWHM, n.d. Web. 19 Oct. 2014.

Taylor, Emily. “Inventions of the Industrial Revolution.” Time Toast. TimeToast, n.d. Web. 19 Oct. 2014.