by Fred Smith, retired administrative analyst with the New York City public school system, with Robin Jacobowitz, Director of Education Projects at the Benjamin Center

New York’s Common Core testing has failed our children. Our recent series, New York State’s School Tests are an Object Lesson in Failure, shows that many students are unable to effectively answer questions on the written portion of the English Language Arts (ELA) tests. (You can access any part of this series via the links box at right.)

A BenCen Series

New York State’s

Testing Failure

Your taxes are paying for a deeply flawed testing system. This series looks at those flaws — and at fixes.

Our analyses show that a substantial percentage of children, particularly third and fourth-grade kids, were unable to write comprehensible answers to three or more written response questions out of the nine or 10 on each ELA exam. That is, they received a zero score on at least three of these questions, which were billed as measuring analytic reasoning and critical thinking. A zero means that a trained scorer deems a response to be “totally inaccurate, unintelligible, or indecipherable.”

If that’s not disheartening enough, we found that the news was even worse for black and Hispanic students in NYC. New York City data allowed us to look at the impact of the exams on different groups; we found that black and Hispanic students received high percentages of zeros on at least three of the questions. It is not insignificant that black and Hispanic students comprise 68 percent of the citywide test population.

But of even deeper concern perhaps, is that that the achievement gap between black and Hispanic students and white and Asian students actually grew after the ELA test was aligned with the Common Core.

First, let’s talk about the percentages of zeroes: Table 1, below, shows that in 2012, the year before the Common Core tests were initiated, seven percent of Asian and white third grade kids got three or more zeros on the written portion of the test, compared with 17 and 18 percent of black and Hispanic children, respectively.

But after the tests are aligned with the Common Core, the percentage just about doubles for all groups to 16 and 15 percent for Asian and white third graders and to 33 and 34 percent for black and Hispanic youngsters. The percentages are relatively consistent through 2016 for these eight-year-olds.

The chart reveals that fourth-grade students experience a similar phenomenon, though there is an inversion for each group in 2014. (Also note that we do not have data for fourth graders from 2016.) We are left to ponder why that occurred: Did the fourth grade class of 2014 have better critical thinkers in it than their counterparts in 2013 and 2015? Did test-takers have better breakfasts that year? Was there something unique to the ELA test given in 2014?

No matter. The results add up to bad news for the entire test population and worse news for our black and Hispanic children.

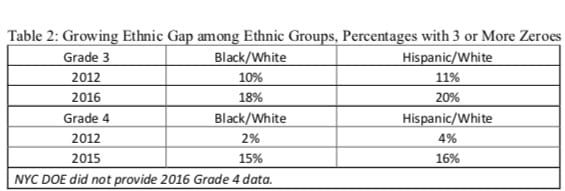

Now, let’s talk about the gap: We’ll stick to the convention of comparing whites to minorities (blacks and Hispanics), leaving Asians out of the mix. The data are in Table 2, below. In pre-Core 2012, the gap between black and white third graders is 10 percent. Then, in 2013 and subsequent years, the gap widens to around 18 percent. Similarly, the spread between white and Hispanic students grew from 11 percent in 2012 to 20 percent after the tests were aligned with the Common Core.

What’s the takeaway? After the statewide ELA exams were aligned with the Common Core standards, the gap between whites and minority students increased. Is this a reflection of bias in the test material and questions? Is it a true measure of the difference in achievement separating the groups? The same questions can be raised about the outcomes in fourth grade.

Read it again. We don’t know why there is a widening differential between groups. And that’s a problem.

Certainly, it warrants further investigation. But this is where the State Education Department (SED) isn’t listening. As we have said previously, the Department stopped releasing all of the testing data, which means that independent researchers and test specialists cannot analyze student responses, or the tests themselves. With Questar—the current testing company—now entering the third year of its $44 million contract, it’s important to have some accountability. We need to better understand the increase in the achievement gap. The SED needs to allow such auditing.

Our studies show that the Common Core-aligned tests leave many students befuddled – and the effect is even greater for black and Hispanic students, and our previous studies show the harsh impact the exams had on English Language Learners and students with disabilities. Further, the achievement gap between white and black, as well as between white and Hispanic students, has increased on the written response questions since the implementation of Common Core-aligned testing. We implore the SED to release the 2017 and 2018 tests and the item-statistics these tests generated like it used to prior to 2012, so that analysts and policymakers can understand, and develop ways to address this situation.

0 Comments

1 Pingback