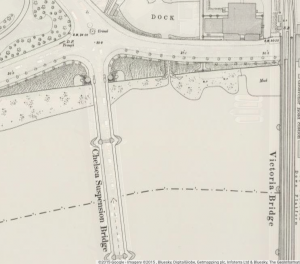

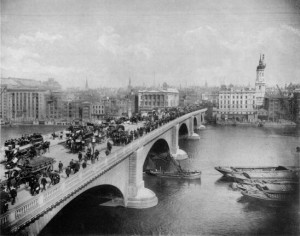

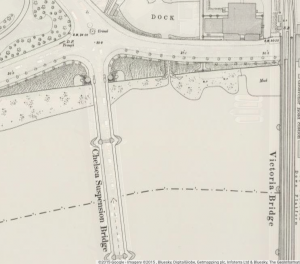

Located in the northwestern region of London, Chelsea was a predominantly well-off and bustling neighborhood that revolved around Chelsea Rd. and the Chelsea Rd. Bridge. In “A Lost Masterpiece,” the main character (who remains nameless) makes his way to the Chelsea wharf and there loads a steamer to travel east up the Thames River. Interestingly enough, Chelsea’s wharves were the first ferry transportation portals along the Thames River, which made Chelsea a fast-developing part of London. In 1816, the steamboat was introduced to the Thames River and by the 1830’s steamboat traffic was booming, especially between Chelsea Bridge and London Bridge. Not only did the town of Chelsea serve as a gateway due to the many wharves that popped up along the Thames, but the Chelsea Bridge also became one of the most used roads/highways by this time as well, as it connected the Royal Hospital to the rest of London .

Located in the northwestern region of London, Chelsea was a predominantly well-off and bustling neighborhood that revolved around Chelsea Rd. and the Chelsea Rd. Bridge. In “A Lost Masterpiece,” the main character (who remains nameless) makes his way to the Chelsea wharf and there loads a steamer to travel east up the Thames River. Interestingly enough, Chelsea’s wharves were the first ferry transportation portals along the Thames River, which made Chelsea a fast-developing part of London. In 1816, the steamboat was introduced to the Thames River and by the 1830’s steamboat traffic was booming, especially between Chelsea Bridge and London Bridge. Not only did the town of Chelsea serve as a gateway due to the many wharves that popped up along the Thames, but the Chelsea Bridge also became one of the most used roads/highways by this time as well, as it connected the Royal Hospital to the rest of London .

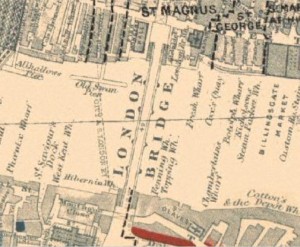

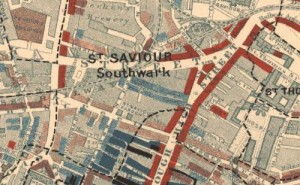

The Chelsea Bridge was erected sometime during the 15th century, under the name Battersea Bridge, but with the introduction of auto-transportation, Chelsea’s reputation of being a travel hub continually grew. With so much access to and from Chelsea, it seems as though during the Victorian Era, and probably the eras to follow as well, Chelsea was a major part of London that really allowed Londoners to use the Thames River for travel. The article, “The parish of Chelsea: Communication,” explains, “in 1844 eight steamboats travelled between London Bridge and Chelsea, four times an hour, and traffic was increasing. Chelsea vestry saw steamboats – quick, cheap, and comfortable – as potentially the common transport of residents of the densely-populated shore.” Egerton’s main character makes this journey in “A Lost Masterpiece,” which is significant because Chelsea Bridge and wharf is what connects the Western wealthy end of London to the slummy, factory ridden east end. The Booth Poverty map shows that during the Victorian era, the areas in and around Chelsea were populated well-to-do- middle-classers, while the area around London Bridge is shaded to indicate the poverty and crime. Chelsea’s bringing together of the contrasting regions of London is also apparent in the way the main character describes his observations once getting off the steamer by London Bridge. He does not see the filth and poverty surrounding him, rather finds the east-end of London delightful and curious:

“The youth played mechanically, without a trace of emotion; whilst the harpist, whose nose is a study in purples and whose bloodshot eyes have the glassy brightness of drink, felt every touch of beauty in the poor little tune, and drew it tenderly forth. They added the musical note to my joyous mood ; the poetry of the city dovetailed harmoniously with country scenes too recent to be treated as memories—and I stepped off the boat with the melody vibrating through the city sounds.”

Although his main character sees the industrial area through an optimistic lens, Egerton’s mention that the music was played mechanically and without emotion is indicative of the actual situation and quality of life that was present in the eastern portion of London. Although the music the main character hears adds more joy to his already joyous mood, the way in which the music is produced is melancholy and representative of the proletariat’s factory labor, which only benefits the bourgeoisie, as the sad music only benefited the seemingly wealthier observing character. Through his mention of Chelsea, especially as the port town the main character uses to access the slums, Egerton is calling attention and awareness to the two extremely opposing “Londons” within the City of London.

Works Cited

Booth, Charles. “Booth Poverty Map & Modern Map (Charles Booth Online Archive).” Booth Poverty Map & Modern Map (Charles Booth Online Archive). London School of Economics & Political Science, n.d. Web. 09 Sept. 2015.

Egerton, George [Mary Chavelita Dunne Bright]. “A Lost Masterpiece.” The Yellow Book 1 (Apr. 1894): 189-96.The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2010. Web. 09 Sept. 2015.

‘Settlement and building: From 1680 to 1865, Chelsea Village or Great Chelsea’, in A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 12, Chelsea, ed. Patricia E C Croot (London, 2004), pp. 31-40. Web. 09 Sept. 2015.

‘The parish of Chelsea: Communications’, in A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 12, Chelsea, ed. Patricia E C Croot (London, 2004), pp. 2-13. Web. 09 Sept. 2015.