Chelsea:

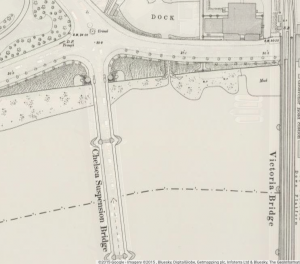

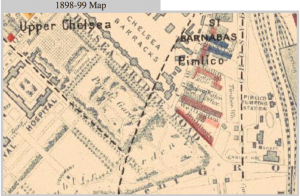

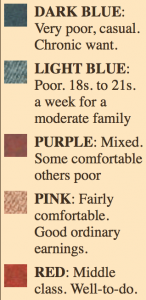

In “A Lost Masterpiece” Chelsea is where the speaker boards a river steamer heading towards London Bridge. Surrounding the Chelsea Bridge Street according to the Charles Booth Online Archive are “middle class, well-to-do” neighborhoods. The speaker also describes his sentiments whilst he is riding the steamer. The steamer ride starts with the speaker in the countryside and then eventually he sees the brick buildings and warehouses covered in a grey soot overtone. The Thames wanders through “fertile meads and beside pleasant banks” as well as “homely villages, retired cottages, palatial dwellings, and populous cities and towns; boats and barges, and the sea-craft of a hundred nations” (Hall), therefore the speaker begins his journey to London in idilic familiar scenery and ends up passing through the area surrounding the river heavily influenced by the industrial revolution.

The importance of Chelsea to the story’s plot and theme is very evident when the character transitions. He boards a river steamer in Chelsea in order to take London Bridge.

The water in the area was polluted and muddy. The speaker says he expects some creature to be washed up on the thick banks of the Thames River. The buildings lining the water are warehouses and made of brick. The speakers describes them to create a chilling imagery of “monster chimneys” as a backdrop for the river ride. The memory of being in the countryside in Chelsea is not forgotten when he reaches London; this sets up the contrast between the two places. Thus, traveling from one place to another could mean leaving one completely different environment to experience a new one—country to city within miles. In addition, The young ladies to the right of the speaker on the steamer shamelessly pick on the speaker and giggle at his appearance and therefore represent the snobbish upperclass society of the area. Clearly there is a stark separation of welfare.

The theme of “A Lost Masterpiece” is that the pace of the city seems superficial and over the top to those from the outside. The woman rushing truly bothers the speaker. His point of contention with her is her pace. For what reason in the world could she be rushing along so feverishly? The speakers has plans to write about his relaxed mentality and the flowers and music in his head so the city dwellers can read it and relax their minds. Nonetheless, the little speeding woman is compared to a wandering Jew or a ghost and it ruins his train of thought and sends his mind into a dark place void of poetry and flowers.

Works Cited:

Egerton, George [Mary Chavelita Dunne Bright]. “A Lost Masterpiece.” The Yellow Book 1 (Apr. 1894): 189-96. The Yellow Nineties Online. Ed. Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra. Ryerson University, 2010. Web. [09 Sept. 2015].

Hall, Samuel Carter, and A. M. Hall. The Book of the Thames. London, Vertue, 1859.

“The Charles Booth Online Archive.” Results. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 Sept. 2015