The Royal Academy of Arts in Burlington on Piccadilly is mentioned in chapter twelve of author Amy Levy’s The Romance of a Shop. Mr. Darrell, a painter and wealthy associate of the Royal Academy has grown fond of a beautiful young maiden, Phyllis, who works in a photography shop. He expressed his desire to paint a picture of her and rather than hanging it in “the profanum vulgus Burlington House” as he originally suggested, he preferred to hang it in his home as “it will show up better at his place” (133). According to The Latin Lexicon online source “profanum” and “vulgus” are Latin terms meaning an “unholy” object and vulgus refers to the state of being ordinary (Alexander). The book references “profanum vulgus, i.e., the vulgar rabble” and according to Merriam-Webster “rabble” refers to the “disorganized collection on things” or a low class of people who could be considered violent (The Romance of a Shop. 133) (The Merriam-Webster Dictionary).

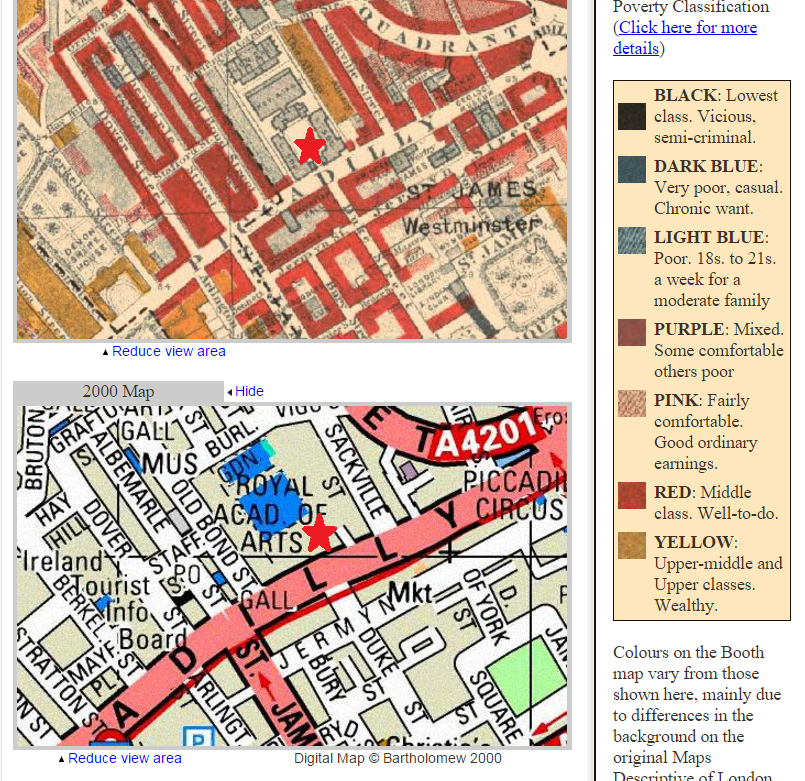

The Charles Booth Online Archives states the Burlington House was situated in direct proximity to the “upper-middle class area and mostly consisted of inhabitants who are “comfortable others poor” and some “middle class” (Charles Booth Online Archives). Also, documented crimes in The Proceedings of Old Baily indicate that starting in the year 1837 and onward offenses in this area consisted of simple theft such as pickpocketing (Old Baily).

These statistics are extremely important to note. Mr. Darrell is considered to be wealthy and of the upper-middle class. He believes Burlington House is a place in which common people congregate to display art forms other than photography. Although The Burlington House is deemed as a world-renowned institution for displaying art, Mr. Darrell prefers not to have his painting of Phylis displayed there. He does not view the inhabitants of the area as being intellectually on his level or of the same socio-economic class as himself. Nevertheless, he perceives the painting of Phyllis in which he depicts a lower class maiden, an employee of a photography shop is not worthy of being exhibited there. To him, although he has captured the working girl’s true beauty he believes her persona would be diminished if her portrait were to be displayed in the gallery with the otherwise disorganized and commonplace collection of art pieces of the Royal Academy.

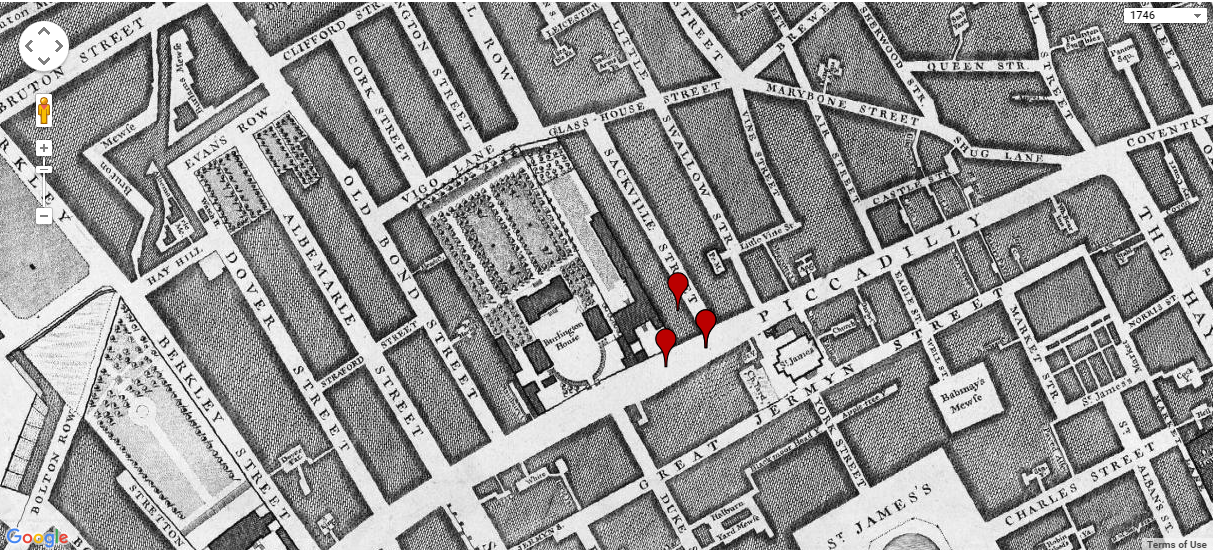

According to The Historical Eye in the article entitle Piccadilly to Regent Street: Then and Now 1896, the Burlington House is dedicated to the Royal Academy of Arts established in 1768, which hosts “painting and sculptures” by British artists (Rees). The British History Online in the article Burlington Arcade states the Italian Renaissance mansion was bequeathed to the Dukes of Devonshire. These high-ranking noblemen lived on Piccadilly and were distinguished in both rank and affluence. In 1854, the venerated house was sold to the British Crown. (Burlington Arcade. British Histories Online).

In the article Burlington House on Dictionary of Victorian London online, the building was partitioned into five collections that were called “The Society of Antiquaries,” “The Linnaean Society”, “The Royal Society of Chemistry”, “The Geological Society” and “The Royal Astronomical Society.” The Royal Academy of Arts, located on the same property, “held the annual exhibition of pictures” (Jackson).

According to Peter Cummingham, Hand-book of London located on Dictionary of Victorian London online; The Royal Academy of Arts was previously located on Trafalgar Square and then at Somerset House. The government expanded the Academy’s art collection and in 1866 chose to move it to Burlington House. The Academy was widely known as “a private society” but, its’ doors were that of a “school open to the public.”

Students selected to attend the program at the Academy were chosen based on their artistic ability. Discerning students were awarded yearly medals based on their astute distinction. Students could choose to study in one of the three branches of learning which included antiquity, living models, and painting. As Mogg’s New Picture of London and Visitor’s Guide to its’ Sights states, professors of the Royal Academy of Arts were known as highly esteemed artists in the fields of “painting, sculpture, architecture, [chemistry] and engravers” (Jackson). The article Pall Mall, South Side, Past Buildings: The Royal Academy in British Histories Online states that complimentary tuition was given to all students. Additionally, seasonal “lectures” were available to the general public, with summer being the prime time for lecturing on painting (Pall Mall, South Side, Past Buildings: The Royal Academy. The British Histories Online).

An exhibition was held yearly at the Royal Academy of Arts in which all artists could enter their creations. However, artistry could not consist of previously exhibited pieces, copies, vignette portraits and no “drawings without backgrounds” were to be entered (Mogg’s New Picture of London and Visitor’s Guide to its’ Sights . Jackson). Also, only art pieces that consisted of painting, sculptures, architect, engraved, seal-cut and medal pieces could be submitted. The proceeds collected from this exhibit went directly to funding the school and other charities (Pall Mall, South Side, Past Buildings: The Royal Academy. The British Histories Online).

This exhibition is referred to as being “one of the most interesting spectacles to an intelligent mind that the capital can boast” (Mogg’s New Picture of London and Visitor’s Guide to it Sights. Jackson). Professional artists were allowed to enter up to eight pieces of work. In contrast, “unprofessional artists” were permitted to enter only one piece of work that would then be presented to the council to be adjudicated. Charles Dickens in his Dickens’s Dictionary of London, states that the yearly exhibit was known as one of the “largest picture shows in the world” (Jackson).

Throughout my research, I could not find references to the practice of photography. Clearly, photography was not considered a legitimate art form. Therefore, a vignette or small portrait photograph was not accepted for submission to the contest. When Mr. Darrell decides not to give the painting of Phyllis to the Burlington House it is perhaps because he is acknowledging the art world does not recognize photography, Phyllis’s’ livelihood as a legitimate art and, in essence, would be rejecting her beauty and her abilities as a working woman and gifted artist.

The Burlington House and The Royal Academy are prominent institutions and lend much credibility to the surrounding area. As such, the region received world recognition for being the hub of esteemed intellect, art, and science. Consequently, the five societies were distinct foundations. They greatly enhanced the credibility of the humanity of the arts and sciences in London. In our class, we have debated the notion of photography being either an art form or science. Clearly, today we view photography as serving both fields. However, during the Victorian Era it was more widely known as science.

Works Cited

‘Burlington Arcade.’ Survey of London: Volumes 31 and 32, St James Westminster, Part 2. Ed. F

H W Sheppard. London: London County Council, 1963. 430-434. British History Online. Web. 26 October 2015. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols31-2/pt2/pp430-434.

Alexander, Keith. “Profanum.” The Latin Lexicon. Keith Alexander. Web. 31 Oct. 2015.http://latinlexicon.org/definition.php?p1=1013239&p2=p.

Alexander, Keith. “Vulgus.” The Latin Lexicon. Keith Alexander. Web. 31 Oct. 2015.http://latinlexicon.org/definition.php?p1=1017645&p2=v.

‘Burlington Arcade.’ Survey of London: Volumes 31 and 32, St James Westminster, Part 2. Ed. F .H W Sheppard. London: London County Council, 1963. 430-434. British History Online. Web. 26 October 2015. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols31-2/pt2/pp430-434.

Lee, Jackson. “Dictionary of Victorian London – Victorian History – 19th Century London –Social History.” Dictionary of Victorian London – Victorian History – 19th Century London – Social History. Dictionary of Victorian London. Web. 31 Oct. 2015.http://www.victorianlondon.org/index-2012.htm.

Jackson, Lee. “Dictionary of Victorian London”- “Victorian London – Entertainment and Recreation – Museums, Public Buildings and Galleries – Royal Academy of Arts.” Victorian London – Entertainment and Recreation – Museums, Public Buildings and Galleries – Royal Academy of Arts. Web. 31 Oct. 2015.http://www.victorianlondon.org/entertainment/royalacademy.htm.

Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster. Web. 31 Oct. 2015. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/rabble.

‘Pall Mall, South Side, Past Buildings: The Royal Academy.’ Survey of London: Volumes 29 and 30, St James Westminster, Part 1. Ed. F H W Sheppard. London: London County Council, 1960. 346-348. British History Online. Web. 31 October 2015. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols29-30/pt1/pp346-348.

Rees, Simon. “Piccadilly to Regent Street: Then and Now 1896.” The Historical Eye. The

Historical Eye, 2015. Web. 31 Oct. 2015. http://historicaleye.com/1896%20London% 20then%20and%20now/piccadilly%20to%20regent%20street.html.

“The Proceedings of the Old Bailey.” Results. The Proceedings of Old Baily. Web. 31 Oct. 2015.

“Victorian Art Institutions: Academies, Schools, Galleries.” Victorian Art Institutions:Academies, Schools, Galleries. The Victorian Web, 5 Jan. 2015. Web. 31 Oct. 2015.http://www.victorianweb.org/art/institutions/1.html.