During the Victorian era, the East End of London gained a reputation for crime and poverty, and was once described as “a terra incognito for respectable citizens.” Located directly outside the walls of the City of London rested the “hub” of the East End—Whitechapel. Famously known for the Jack the Ripper murders, Whitechapel easily became one of the most notorious slums in Victorian London (Diniejko).

Origins of Whitechapel’s Slums

Whitechapel wasn’t always a slum. Up until the end of the 16th century it was a “relatively prosperous district” (Diniejko). It wasn’t until the mid-18th century, when the less desirable industries (tanneries, breweries, foundries) began to grow in the East End, that areas within Whitechapel began to deteriorate. As the industries grew, they attracted more and more workers: immigrants (typically refugees) and Englishmen from the countryside (Whitechapel’s Sordid History). By the mid-to-late 19th century, Whitechapel became overcrowded and crime infested (Diniejko).

Slums, Poverty and Disease

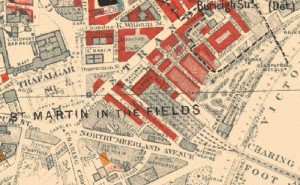

According to the Charles Booth Poverty Map of 1898-99, Whitechapel as a whole appears to be a fairly economically-sound district—with the majority of areas being “fairly comfortable.” Among these areas you will find multiple areas of light blue (“poor”), dark blue (“very poor”), and black (“lowest class [vicious, semi-criminal]”). These areas were the locations of slums.

What did these slums look like? As stated previously, Whitechapel was devastatingly poor. As Whitechapel became overcrowded, multiple impoverished families were forced to live together (often up to nine people), crammed into small single rooms. Poverty also created an increase in common lodging houses. In Whitechapel, over 200 common lodging houses were created to house the 8,000+ “homeless and destitute” people per night. Apart from overcrowding, conditions in these shared houses were atrocious; one of the most predominant issues was the lack of proper ventilation and sanitation. Due to these dreadful environments, diseases like cholera spread (Diniejko).

Crime

Of all the recorded crimes in Whitechapel from 1837-1901, 2234 records were found with theft being the majority: 1376 cases of basic theft (extortion, embezzlement, pocketpicking, grand larceny, petty larceny, animal theft, etc) and 263 cases of violent theft (robbery, highway robbery, etc.) (Old Bailey).

Though Whitechapel is known for the infamous Jack the Ripper murders, only 95 cases of “killing” were recorded: 41 cases of murder, 51 cases of manslaughter and 3 cases of “infanticide,” “treason,” and “other” (Old Bailey). Though 95 is still relatively high, it in no way makes up the majority of crime in Whitechapel. With that being said, it can be suggested that the murders of Jack the Ripper created more hysteria surrounding the “murderous” conditions in Whitechapel than what existed in reality—though reality was still rather bleak.

Women and Prostitution

Prostitution, however, was a major problem. For many impoverished women living in the East End, prostitution was a primary source of income, “paying anywhere from a loaf of stale bread to three pence.” The estimated total of female prostitutes in Whitechapel in 1888 was 1,200. Prostitution was, of course, not a glamorous trade. By the time women reached the age of twenty, they often would look twice their age due to heavy drinking, as well as their rough lifestyle. Women would often seek comfort in alcohol to escape the reality of their life, often leading to brutality and violence as a result of drunken brawls—a commonplace in Whitechapel (Scanlon).

Slum Clearing

In 1875, the Artisans’ and Laborers’ Dwellings Improvement Act was passed by Parliament. It was an act designed by Richard Cross to buy up the slums, demolish them and then rebuild. Its purpose was “to purge the lawless population of the common lodging houses from the neighborhood” (Jenks)—a way of “demolishing” crime and rebuilding lawful residences and neighborhoods. The first two “test” areas for demolition were the slum areas of Holborn and Whitechapel because they were considered to be some of the most dangerous and immoral (Yelling). The houses targeted in Whitechapel were those on Flower and Dean Street. However, the plan to “remove the nests of disease and crime” backfired. The evicted occupants relocated to Dorset Street and White’s Row, and the cycle continued all over again (Gray).

Whitechapel & Dorian Gray

Whitechapel is mentioned twice within the first five chapters of The Picture of Dorian Gray: in chapter two and chapter three. In chapter two, Dorian realizes that he forgot about his promise to go to the club in Whitechapel with Lord Henry’s aunt: “”I am in Lady Agatha’s black books at present,” answered Dorian with a funny look of penitence. “I promised to go to a club in Whitechapel with her last Tuesday, and I really forgot all about it. We were to have played a duet together – three duets, I believe. I don’t know what she will say to me. I am far too frightened to call.”” In this chapter, Dorian, not yet touched by Lord Henry’s influence, acts with his innocent qualities and feels guilt; his incredibly poor qualities have not yet been unveiled. However, his guilt does not seem to stem from forgetting the people of Whitechapel, but from the fear that he has disappointed someone of higher privilege—Lord Henry’s aunt—and that he will reap the consequences of his negligence.

Furthermore, when he reveals that he “forgot all about” going to Whitechapel, the “hub” of the East End that represents those in poverty, it foreshadows the events to come—especially his treatment of Sibyl Vane and her fate to follow. His disregard for those he deems “beneath” him turns out to be the leading cause of his demise. Just like the government’s disregard for those living in Whitechapel’s slums during the clearings, Dorian’s lack of concern for others in the interest of his own personal gain backfires. He loses more than he gains. (May I also mention the irony of the fact that she works at a theatre in Holborn, the other disregarded location of slum clearings that displaced the lives of already trodden people.)

In chapter three, Lord Henry and Dorian are at Lady Agatha’s for lunch. When Lady Agatha calls Lord Henry out on trying to persuade Dorian to give up the East End, she remarks: “But they are so unhappy in Whitechapel.” In which Henry replies, “I can sympathise with everything except suffering […] I cannot sympathise with that. It is too ugly, too horrible, too distressing. There is something terribly morbid in the modern sympathy with pain. One should sympathise with the colour, the beauty, the joy of life. The less said about life’s sores, the better” Because Henry is obsessed with art and aesthetic beauty, he chooses to ignore the problems the East End face simply because they are not aesthetically pleasing and therefore, not worthy of his time. His disregard for the problems East-Enders face is later exhibited when Sybil commits suicide and his reaction is not one of horror or pity, but of carelessness as he tries to explain her death in terms of art and beauty.

When Sir Thomas continues by saying, “Still, the East End is a very important problem,” Henry replies, “Quite so […] It is the problem of slavery, and we try to solve it by amusing the slaves.” Lord Henry’s point here is valid. Instead of donating money, clothes, or shelter—the simple life necessities the East-Enders are in dire need of—the wealthy travel to Whitechapel to “amuse” the poor (but mostly, themselves). Their actions do not help the poor, but instead, only gives gratification to the wealthy who want to feel as if they’ve done something “charitable” and “good”—as if the poor need their presence to remind themselves of, and to juxtapose, the impoverished state they find themselves in.

When we return to Whitechapel later in the novel, in chapter eleven, Dorian has ventured into Whitechapel but not for the purposes of charity. Instead, as Dorian becomes more and more corrupt, he begins venturing into the East End for the purpose of committing crimes and doing drugs. Interestingly, when he ventures into the East End, he does not disclose his location to friends and acquaintances. In fact, he goes to the East End in disguise, dressed in the clothes of a commoner. His double life of existing in juxtaposed worlds, the West End and East End, is a direct parallel to his physical and mental double life—the ugliness of his soul and the beauty he wears from the painting. I believe an interesting commentary is being made here about class and location. Dorian, who lives in the wealthy and aesthetically pleasing West End, has the outer aesthetic beauty associated with the West End, but the hideous personality and morals associated with the ugly, run-down East End. Does outer beauty mean you live free of corruption? How much can aesthetic beauty really say about a person, and how much can it really say about the wealthy West End? You can dress up a monster in sleek trousers and a velvet coat, but it’s still a monster. Wilde, I believe, is blurring the lines between what separates the East End from the West. They are two sides of the same corrupted coin.

WORKS CITED

“Booth Poverty Map & Modern Map (Charles Booth Online Archive).” Charles Booth Online Archive. London School of Economics & Political Science, n.d. Web. 23 Nov. 2015.

Diniejko, Andrzej. “Slums and Slumming in Late-Victorian London.” The Victorian Web. The Victorian Web, 3 Oct. 2013. Web. 23 Nov. 2015.

Gray, Drew D. London’s Shadows: The Dark Side of the Victorian City. New York: Bloomsbury, 2010. 122-23. Google Books. Google Books, 1 July 2010. Web. 23 Nov. 2015.

Jenks, Chris. Urban Culture: Critical Concepts in Literary and Cultural Studies. Vol. 4. London: Taylor & Francis, 2004. 197-98. Google Books. Google Books. Web. 23 Nov. 2015.

“The Proceedings of the Old Bailey.” Old Bailey Online. The University of Sheffield, n.d. Web. 23 Nov. 2015.

Scanlon, Gina. “Whitechapel.” BBC America. BBC, 13 Dec. 2012. Web. 23 Nov. 2015.

“Whitechapel’s Sordid History.” Peach Properties. Peach Properties (UK) Ltd., 13 May 2015. Web. 23 Nov. 2015.

Yelling, J. A. Slums and Slum Clearance in Victorian London. New York: Routledge, 2012. 24. Google Books. Google Books, 21 Dec. 2006. Web. 23 Nov. 2015.