With development starting as early as the sixteen hundreds, Piccadilly runs across London and serves as the main highway that connects the west end to the east end (Piccadilly, Southside). Piccadilly runs just north of Green Park and south of the Royal Academy and meets Regent Street at the famous Piccadilly Circus. Not only did Piccadilly serve as the gateway from the West to the metropolitan area of England, but it was also the site of many newly erected mansions throughout the seventeenth century. Right from the beginning of Piccadilly’s history, the street has been an area of wealth, as we can see on the Booth Online Poverty Map.

Due to the area’s apparent wealth, throughout history, this area has been the setting for political grounds. In the article, “Mansions in Piccadilly,” we learn that, “For a century and a half this house has been one of the special rendezvous of the Whig party. “Three palaces in the year 1784,” writes Sir N. W. Wraxall, “the gates of which were constantly thrown open to every supporter of the ‘Coalition’ (against Pitt), formed rallying-points of union.” One of these was Burlington House, then tenanted by the Duke of Portland; the second was Carlton House, the residence of George, Prince of Wales; the third was Devonshire House, which, ‘placed on a commanding eminence opposite to the Green Park, seemed to look down upon the Queen’s House, constructed by Sheffield, Duke of Buckingham, in a situation much less favoured by nature.'” Due to Piccadilly’s plethora of wealth, many shop owners, especially booksellers, started opening up stores in what is now known as one of the most famous shopping areas of London. Many book shops and publishing houses were opened up, and by, “1850 or 1851 the firm of Chapman and Hall came from the Strand to No. 193 Piccadilly, where it remained until its removal to Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, in 1881. Chapman and Hall’s authors included the Brownings, Trollope, Meredith and Dickens” (Piccadilly, South Side). This area became more and more popular, especially for authors and other cultured people. Soon enough, the Royal Academy was developed right off Piccadilly, as well as restaurants, inns, and many more shops.

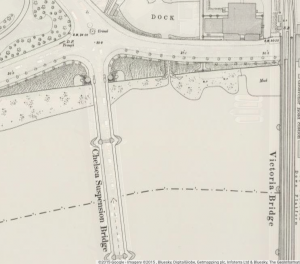

As Dorian describes how he met Sibyl Vane to Lord Henry, he begins by telling Lord Henry, “As I lounged in the Park, or strolled down Piccadilly, I used to look at every one who passed me, and wondered, with mad curiosity, what sort of lives they led” (52). We learn that Dorian, instead of roaming around the wealthy, cultured neighborhood of which he was a part, decides to head eastward in order to find true beauty. It is interesting that Dorian, although immersed in the arts, wealth, and beauty of Piccadilly, felt he needed to seek true beauty elsewhere; this detail, in my opinion, foreshadows Dorian’s spiral downward. He no longer finds beauty in the intellectual and artistic aspects of his upper-class life, rather finds amusement through grime and sin.

Works Cited

“Piccadilly, South Side.” Survey of London: Volumes 29 and 30, St James Westminster, Part 1. Ed. F H W Sheppard. London: London County Council, 1960. 251-270. British History Online. Web. 1 December 2015.

Walford, Edward. ‘Mansions in Piccadilly.’ Old and New London: Volume 4. London: Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1878. 273-290. British History Online. Web. 1 December 2015.

Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2003. Print.