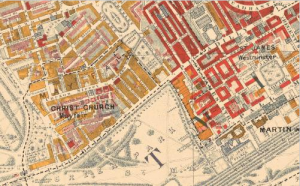

In Amy Levy’s The Romance of a Shop, The Sycamores is the name of Sidney Darrell’s studio in St. John’s Wood. Though the name of the studio is not traceable—it is likely fictional—St. John’s Wood was a wealthier area. The majority of St. John’s Wood was primarily upper and middle class (Charles Booth). Considering that Sidney Darrell is of a higher class, it makes sense to place his studio in this area. The Sycamores is mentioned and visited several times throughout the novel, and is even important enough to be the title of an entire chapter. The first time this place is visited, Gertrude is going to photograph one of Darrell’s paintings. The place is described as “fitted up with all the chaotic splendour which distinguishes the studio of the modern fashionable artist; the spoils of many climes, fruits of many wanderings, being heaped, with more regard to picturesqueness than fitness, in every available nook” (Levy 72). This description emphasizes the social class of Darrell, as well as the difference between his and Gertrude’s classes. The fact that Gertrude explains this place as being so grand and the fact that “she only carried away a prevailing impression of tiger-skins and Venetian lanterns” reveals her lower class. She is not accustomed to the expensive tastes of the high class.

The next important and lengthy mention of the Sycamores is in the chapter titled “The Sycamores.” In this chapter, Gertrude and Lord Watergate go seeking Phyllis, who has decided to run away with Darrell and marry him. At The Sycamores, Phyllis has evolved into a whole new person. This transformation is perceived because of the expensive clothing and makeup that she wears: “a beautiful wanton in a loose, trailing garment, shimmering, wonderful, white and lustrous as a pearl … her brown hair turned to gold in the light … with diamonds on her slender fingers” (Levy 146). She has been removed from her modest surroundings and has become immersed in high class life. This strongly emphasizes the theme of social class because it shows how intensely one’s image can change by assuming the wardrobe of high class. Though Phyllis is still the same class she was before, she is seen as more beautiful and glorious because of the clothing she is wearing.