Maisie Miller

Online assignment #5

My Ngrams focused on words assigned to women by their male counterparts, whom mainly published these words, during the Victorian age. I choose hysteria and prostitution as my main focus because I was curious to see how the “fallen” women’s roles played against each other. I was surprised to see that they met and switched positions on the graph.

Further research into the words, described a dark time for women with mental illness, ( or misdiagnosed illness), as well as a period of time where options were limited for employment and resources. In Victorian times, a woman could be considered “unbalanced” due to a variety of causes, including: menstruation-related anger, pregnancy-related sadness, postpartum depression symptoms, disobedience, chronic fatigue syndrome, anxiety, and prostitution, among other things. Victorian society emphasized female purity and supported the ideal of the “true woman” as wife, mother, and keeper of the home. A hysterical female was one who could be nervous, eccentric, and/or exhibit erratic behaviour, the epidemiology of hysteria eluded medical explanation in the Victorian era. For hysterical women and their families, the asylum offered a convenient and socially acceptable excuse for inappropriate, and potentially scandalous behavior. Prostitution or, “fallen woman,” were usually of the lower classes, and had strayed from the idea of true womanhood by giving in to seduction and sin.

(Cartoon’s of prostitutes; http://profpoofpof.blogspot.com/2013/11/prostitution-in-victorian-times.html Women in asylum for committing the biggest sin https://victorianparis.wordpress.com/2011/10/23/degrees-of-prostitution/ )

“Hysteria” starts at the lower portion of the graph, while “prostitution” begins at a higher point on the y axis. Around 1853, “prostitution” and “hysteria” meet and finally cross each other, reversing their previous positions. “Hysteria” ends up above “prostitution” on the y axis. This could be due to a number of things, one being that the use of the word “prostitution”, was thought of as vulgar in certain levels of society, to describe women who practiced sex acts with men for money. Whereas “hysteria” developed as an widespread mania.

(Books on prostitution, notice the titles. http://www.indiana.edu/~liblilly/offthepedestal/otp5.html )

In 1864 the first of the Contagious Diseases Acts was passed. It required any allegedly diseased prostitute to undergo an inspection (the allegation may be made by an infected enlisted man). If she was found to be infected, she could be held in a Lock Hospital for up to 3 months. This was only a temporary measure, until more stringent acts could be accommodated. The Contagious Diseases Act of 1866 allowed a special police force to order women to undergo fortnightly inspections for up to a year. By 1869, the Contagious Diseases Act required prostitutes to be officially registered and to carry cards, it increased inspection stations and targeted towns from 12 to 18, and increased lock hospital incarceration to 9 months, which can largely contribute to the decline of the word use. The graph reflects this, though doesn’t perfectly add up. This could be due to an in flow of issues regarding “prostitution”, perhaps a particularly large amount of vernal diseases spread during the rise on the graph.

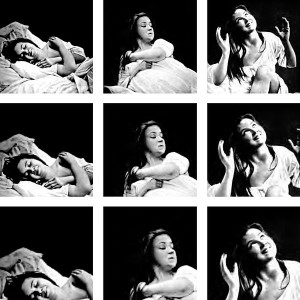

(Public Domain Photo taken by Jean-Martin Charcot in 1878 during his experiments using hypnosis to treat hysteria patients.)

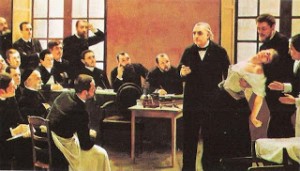

Hysteria’s rise is evident from it’s actual evolution, and subsequent diagnosis, during the Victorian era. In the Victorian Era, doctors discouraged physical activity by women, because they believed ridiculous medical conditions would result from it. Among a range of other concerns, doctors argued that physical exertion in women might cause their organs (particularly the reproductive organs) to become dislodged and wander around the body, causing all types of problems. As The National Institutes of Health explains hysteria in the 19th century;

“Hysteria is a pathology in which dissociation appears autonomously for neurotic reasons, and in such a way as to adversely disturb the individual’s everyday life. Janet studied five hysteria’s symptoms: anaesthesia, amnesia, abulia, motor control diseases and modification of character. The reason of hysteria is in the idée fixe, that is the subconscient or subconscious. For what concerns eroticism, Janet noted that “the hysterical are, in general, not any more erotic than normal person”. Janet’s studies are very important for the early theories of Freud, Breuer and Carl Jung (1875-1961) “.

(Professor Jean-Martin Charcot demonstrates hypnosis on a “hysterical” patient. This image is in the public domain because it’s copyright has expired.)

A physician George Taylor in 1859 claimed that a quarter of all women suffered from hysteria. Hysteria was more commonly used to describe prostitutes, even. Their “struggles”, real or not, were dismissed as simply mental illness. The tragedy of women’s status and associated language can be seen in this graph. The words ascribed to women during the Victorian age hold a heavy weight of a untold story, echoing in these whispered words.

Sources:

Web, https://www.lib.uwo.ca/archives/virtualexhibits/londonasylum/docs/surgeryamonginsane.pdf

Web, http://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/prostitution

Web, http://cai.ucdavis.edu/waters-sites/prostitution/FallenWomen.htm

Web. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3480686/

Images:

http://profpoofpof.blogspot.com/2013/11/prostitution-in-victorian-times.html

http://www.indiana.edu/~liblilly/offthepedestal/otp5.html

http://unhingedhistorian.blogspot.com/2013/08/the-insane-victorians-hysteria-was-real.html