In “The Man With the Twisted Lip,” London Road is briefly mentioned as Sherlock and Watson begin their dash to finally solve the mystery of Mr. Neville St. Clair’s disappearance. Upon further research, I learned some interesting facts about the road that had little significance in the actual Sherlock Holmes story. Unfortunately, there are over twenty roads called “London Road,” just in the city of London, alone! So many of the facts that I saw were not entirely accurate due to the inability to distinguish between multiple roads. Since many of the websites are not specifically based around Victorian London, it was more difficult to find the correct road.

By using the Old Bailey Proceedings through Locating London, I was able to find that there were not many crimes committed on the road, but of the ten crimes that came up in the search results, five of them were highway robberies, and three involved animal theft. The first result was of a man names James Coates, who viciously stole a diamond ring from Mrs. Elizabeth Atley. He was sentenced to death for this crime (“James Coates, highway robbery”). I also learned that the London Road in Ipswich, not in London, is apparently site of the flat of Steve Wright, who murdered five women in 2006, an event about which a movie and a musical were written (both called London Road).

While looking at the OS Town Plan of Victorian London, I can tell that London Road has not changed much, and is still a major road in the city. Much of the information about London Road on British Histories contained information about religion. It was interesting because several of the articles were about religions that do not dominate London, such as Judaism and Islam. There are also many bits of information about monuments and buildings on the road.

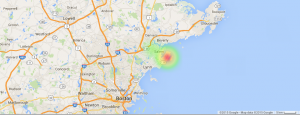

The Charles Booth website offered the most useful and accurate information, despite having the worst design of any of sites. The website shows a map of London and color codes each street based on economic class. It shows London Road in pink, which means that the average economic state of people on London Road back in Victorian London was “Fairly comfortable.”

Works Cited

Doyle, Arthur Conan. London: Strand, 1891. Short Stories: The Man With The Twisted Lip by Arthur Conan Doyle. East of the Web. Web. 6 Nov. 2015. <http://www.eastoftheweb.com/short-stories/UBooks/TwisLip.shtml>.

“Search.” British Histories. University of London, n.d. Web. 6 Nov. 2015. <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/search?query=%22London+Road%22>.

“Booth Poverty Map & Modern Map (Charles Booth Online Archive).”Booth Poverty Map & Modern Map (Charles Booth Online Archive). London School of Economics and Political Science, n.d. Web. 6 Nov. 2015. <http://booth.lse.ac.uk/cgi-bin/do.pl? sub=view_booth_and_barth&args=531720%2C179260%2C1%2Clarge%2C0>.

“James Coates, highway robbery. 15 January 1702 (t17070115-7).” Old Bailey Proceedings Online. Web. 6 November 2015. http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t17070115- 7&div=t17070115-7&terms=+London%20+Road%20#highlight