A Digital Humanities project must be, above all else, holistic. It must encompass all elements of a topic that are available to be documented. The ease of access to said information that the internet provides is unprecedented in human history, and that means there is no excuse to use every bit of proof possible to prove any hypothesis, or any imagery to create any scene. That said, there are a few essential elements which must go into a DH project so as to reach this lofty goal.

A bevy of archival data: Simply, at the most basic level, there must be information present to establish the idea being proposed. Some type of base record must be present; for example, if one were to document crime in London during the 19th century, the first stop would be the Old Bailey archives, where thousands of such examples may be found. These bits allow the project maker to contextualize and form the skeleton of the project.

Geographic information: Maps are good. If it’s a cultural project trying to demonstrate influences on Shakespeare’s writing, then showing migration, population density, and plague victim maps during his lifespan can be vital to showing points of influence. Of course, this is absolutely non-negotiable for map-based projects, but GIS data can greatly enhance even the most elaborately assembled of projects.

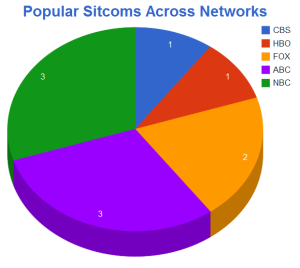

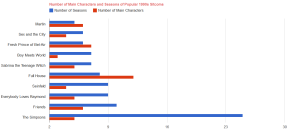

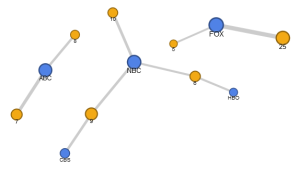

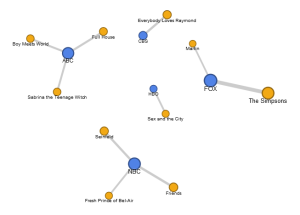

Organized displays: A good DH project must have information presented in a human fashion: infographics and well designed presentations are solid choices, but hastily assembled slideshows and narrated videos are far too limited to actually depict anything. Augmented reality and GIS map overlays are cutting edge and, if someone has the capacity to utilize them, they should consider it.

Supporting sources: If any non-primary source articles exist about your topic, it doesn’t hurt to lump them in. While primary source is key, having someone accredited backing up your project (having come to the same conclusion, or, at the least, a supporting one), never hurts.

Relevancy: All data and referenced sources must be relevant to the topic. Shoving information in people’s faces is not informing them, it’s overwhelming them.