Searching through shelves of old books is a thrilling experience. I was unsure of what to expect at first with this project. I questioned whether or not everyone was going to be able to find marginalia or some sort of vintage markings in the books. My plan was to write down call numbers of books that seemed promising – books in the genre of philosophy, history, poetry or religion. I searched through all of the books I had written down with no luck in margin notes or other handwritten surprises. It was then when I decided to navigate the shelves by myself to seek out something interesting.

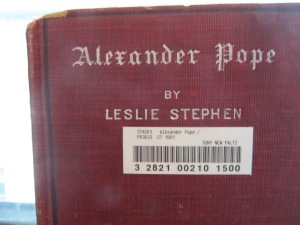

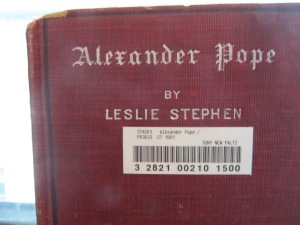

Alas! Something worth writing about. I should mention that of all the books I carefully thumbed through prior to finding Alexander Pope by Leslie Stephen, there was a lot of underlining. I kept searching through other books until I found some sort of notes written in the margins because that was the most rewarding find. The author of this 1901 biography is Leslie Stephen, a 19th century British philosopher. This book is about the life of Alexander Pope who was an 18th century English poet. I tried to examine who wrote the marginalia in order to better understand it. Someone who may have been a philosophy or English student or generally interested in poetry or philosophy may have been the source of the minimal marginal notations. Unfortunately there did not appear to be any cryptic messages or names to decode in the notes. Anything written down in this book seems to have been a confirmation or agreement/disagreement of what was read. Aside from the handwritten cursive margin notes, there was also a vast amount of underlining all throughout the text.

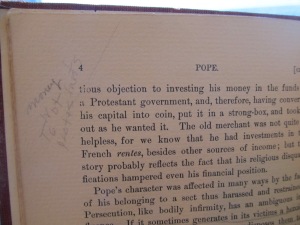

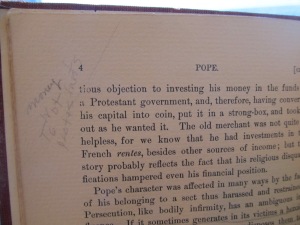

The first bit of marginalia I encountered reads, “money not to protestants”. In this passage the author is describing how Pope had “a conscientious objection” to supporting the Protestant government and saved money himself. The margin note reminds me of something one would write if they were trying to remember a certain point being made to relocate quickly back to that part of the text. Sometimes when I read I benefit from writing down a terse reiteration of the point in the margin so that I can easily find the part in the text I am looking for. Perhaps the person who wrote this was a teacher or explained the book to other people.

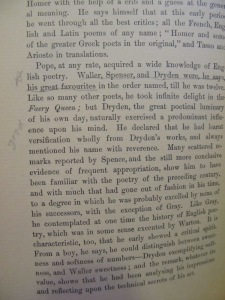

The photo above shows a starred sentence and a simple marking of “good” next to a sentence. There is an obvious agreement with a statement and marking of something that is deemed important by whoever scribbled in the book. The sentence that is underlined and has a star in the margin reads, “Waller, Spencer, and Dryden were, he says, his great favourites”. These three English poets were Pope’s earliest inspirations. Stephen writes how Dryden “naturally exercised a predominant influence upon his [Pope’s] own mind”. This sentence is labeled as being “good”. Perhaps the person who wrote the notes admired the work of Dryden also and felt that the influence he had upon Pope was a good thing. Or maybe the person simply enjoyed the flow of the sentence? They may have also agreed that the work of Dryden strongly influenced the work of Pope by comparison.

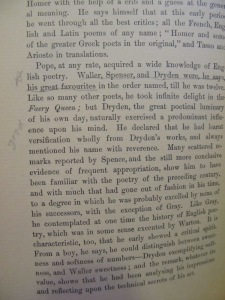

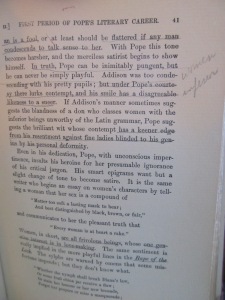

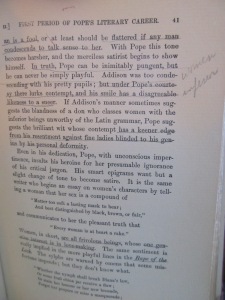

I attempted to decipher the illegible cursive words in the above photo but had difficulty in doing so. In this passage the author is describing how Pope can be pungent but never simply playful. This line and most of the paragraph about Pope’s personality is underlined. Even though I cannot read exactly what the margin note says, I feel that it is an important part of understanding who the source of margin notes is. If we look at what types of things they marked up it may show a pattern of thinking or a way of teaching. The other margin writings are about Pope’s financial habits, his childhood inspirations, his personality, and in the last photo below his love life. One can surmise that the author of the marginalia was certainly interested in the very personal details of Pope’s life. To try and understand the person writing the short margin notes is a challenge given what they have left. Creating my own perception about who they were given the evidence I have is a tantalizing journey. The further I read into the marginalia, the more I want to figure them out.

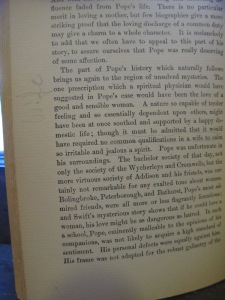

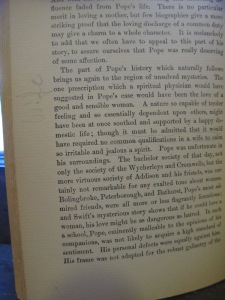

Something interesting about this last bit of marginalia is its vertical positioning and rather large size. Compared to the other bits of text this note is much larger and oriented differently in a way that is kind of curious. The adjacent paragraph talks about Pope’s romantic life and how he was too jealous and mean of a man to marry. Why the marginalia is written differently is unbeknownst to me. My guess is that the person either fervently wanted to remember this portion of the text about his love life and wife situation, or it was strikingly important in another way to them. There are other examples of marginal notations and underlining on later pages in the book but they are mostly illegible doodles in comparison to the ones I chose to highlight in this blog post. With all of the evidence in my hands, and a lot of time and thought, I have conjured up an idea of what the person writing all of these notes had in mind. I envision them to be a male, considering the fact that philosophy and poetry of the 19th century seem to be predominantly male dominated fields. They were most likely either a teacher or a student of philosophy or English, interested in the life and work of Alexander Pope. This person was probably mysterious and cerebral since the majority of their notes were short. They were also probably interested in love and desire. The “wife” marginalia was the largest note in the text and it reflected a particular interest in the writing about love. This analysis is basic and lacking true proof of who the person was, although it was a fun adventure figuring them out myself.

Book Tracing is a unique and interactive experience that allows us to get inside the minds of readers of the 19th and early 20th centuries. It is an opportunity to get lost in a book in a different way. It gives the student the chance to explore early ideas of love, art, history, and other topics. I found this assignment engaging and exciting and had a fun time browsing the library to find something so interesting. Now I will always peruse the shelves of a library with an open eye to catch any torn spines or handwritten titles.

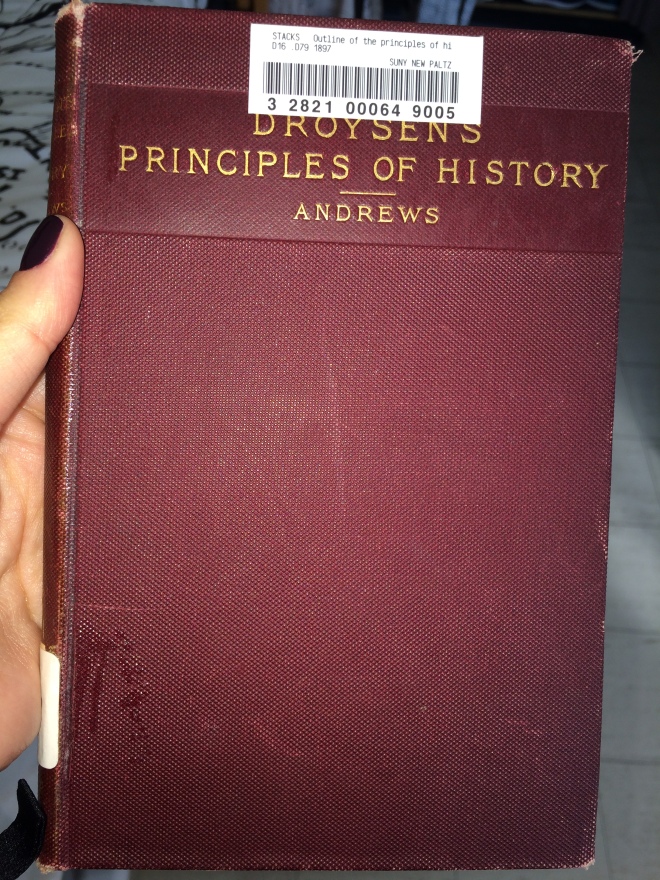

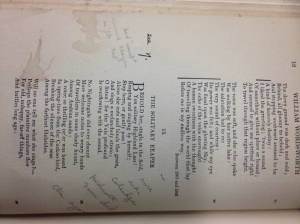

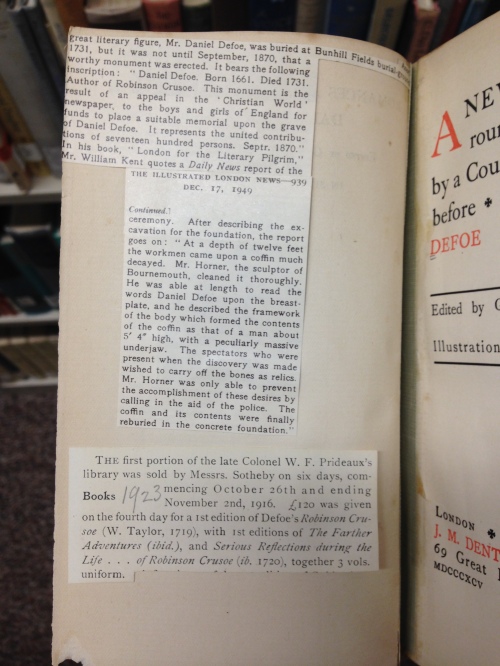

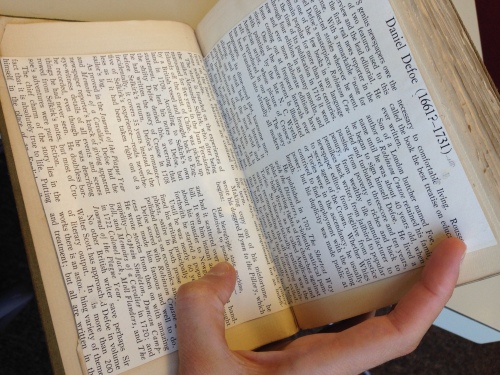

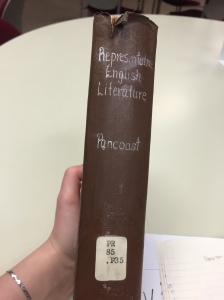

book is a copy of the Representative English Literature: From Chaucer to Tennyson, written by Henry S. Pancoast, published by Henry Holt and Company. This copy is dated at 1895, with the call number PR.85.P35. According to the book’s title page, Pancoast was an English literature lecturer. A Google search revealed his work on

book is a copy of the Representative English Literature: From Chaucer to Tennyson, written by Henry S. Pancoast, published by Henry Holt and Company. This copy is dated at 1895, with the call number PR.85.P35. According to the book’s title page, Pancoast was an English literature lecturer. A Google search revealed his work on