https://www.google.com/fusiontables/DataSource?docid=1jNGQNPrwU-j8oWzP-gU5fKlYIC9CWThhZDruIx29

Google Spreadsheet Info

Cards

map locations of videos

Pie graph

Bar graph

Donut graph

https://www.google.com/fusiontables/DataSource?docid=1jNGQNPrwU-j8oWzP-gU5fKlYIC9CWThhZDruIx29

Google Spreadsheet Info

Cards

map locations of videos

Pie graph

Bar graph

Donut graph

Click here to see our mapping project for A Case Of Identity!!

-Christine, Emily, Hannah

My designated area to study was Tottenham Court Road, which is briefly referred to in “A Case of Identity.”

According to the Charles Booth Archive map, Tottenham Court Road itself was mostly red/middle class, or well to do. The surrounding areas contain mostly pink, purple, and dark blue: “fairly comfortable, good ordinary earnings”,”some comfortable,others poor”, and “very poor.” Nearby Bedford Square is colored yellow, signifying an upper class area.

Booth’s journal notes from walks with Constables around District 3 (which included Tottenham Court Road) in 1898 include descriptions of prostitutes, drunkenness, crime, and broken windows. These descriptions seem to match Booth’s harsh judgements under the “dark blue” poverty category on the map that surrounded Tottenham Court Road. A brief search on The Old Bailey database (starting in 1881 when the story was published) revealed crime clustering around theft. Continue reading

For this assignment, I decided to focus on Fenchurch Street, a location that was mentioned in the Sherlock Holmes story A Case Of Identity. In the story, Fenchurch Street is the location of Miss Sutherland’s step-father’s place of business. Located just around the block from here is Miss Sutherland’s fiancee’s home on Leadenhall Street, which (SPOILER ALERT) turns out to be Miss Sutherland’s step-father. You can see a picture of Fenchurch Street on a map I got from Victorian Google Maps below:

When I looked at the Charles Booth Online Archive, I found out that during the 19th century Fenchurch Street was a very poor area, as you can see on the map and color guide below. The black and blues show that people of the lowest classes lived in this area. This relates back to the Holmes story because Mr. Windibank, Miss Sutherland’s step-father, tried to pose as another man to make Miss Sutherland fall in love with him so he could eventually marry her and take all her money. Mr. Windibank’s place of business was also located just around the block from Fenchurch Street on Leadenhall Street. This area was a good location for Arthur Conan Doyle to put both of Mr. Windibank’s identities in because it shows that he has very little money. If he lived and worked in a different area it wouldn’t make as much sense to the story.

On the Old Bailey Archive, I did a search on my location and found a list of the crimes committed throughout the 19th century. Most of these crimes listed were for all things theft related, like grand larceny, shoplifting, pickpocketing, and even a couple of theft related murders. When I looked at the Locating London website, I found similar results. Then I decided to look at the British History Online website. When I searched my location on there, I found many texts involving businesses and factories, where I learned that this area held many businesses and industries and probably had many jobs that people of the working class had. I’m not saying that poor people were more likely to be criminals, but in order to survive and support their families people of the lower classes needed to do what they could, and theft was probably a last resort option for them to get necessities.

I chose to focus on Leadenhall Street from the Sherlock Holmes story, A Case of Identity for this mapping/research assignment. This image is screen-shotted from the Victorian Google Maps website. Leadenhall Street is the thick, long street running horizontal through the image.

On the Old Bailey Archive I did a search of Leadenhall Street in the 1800s and found man phrases that much of what came up seemed business related, as if Leadenhall was a bustling, though not incredibly wealthy, business district with many places of employment and local businesses. Here are some examples of what I found that lead me to make this conclusion:

-“…I am a clerk at the post office, 114, Leadenhall Street…”

-“…Holder Brothers, Ship brokers, 146, Leadenhall Street…”

-“…he was an advertising agent in Leadenhall Street…”

-“…I am a printer, of 18, Leadenhall Market…”

-“…I am a tea importer, of 158, Leadenhall Street…” etc.

On the Charles Booth Online Archive I searched for the Street and came up with the following 1898-99 map.

According to the legend, the coloring of the map showing the surrounding areas of Leadenhall Street indicate that this was not a wealthy area. It seems that most of this area (the light blue range) is poor and some (the dark blue) indicates very poor areas. I can’t really tell if there are actually dark blue areas or if it’s just light blues layered on top of each other making certain spots look darker. Anyway, from this information and what I previously discovered about the many businesses along Leadenhall Street, it seems that it was a very working class area where people just barely managed to scrape buy and support their families and provide the necessities. Maybe there aren’t quite and “very poor” dark blue areas because there are lots of small local jobs in the area so people are not in the range of “chronic want.”

On the Locating London website, I did a search of Leadenhall Street to discover what typed of crime were reported in this area in the early 1800s. What I found were that all of the offenses were related to theft: pickpocketing, grand larceny, coining offenses, theft from a specified place, shoplifting, highway robbery, etc. I supposed this makes sense if the area was full of businesses and people just barely making it by. I’m not associating the poor with the crime, but these people were, in some way, wanting (indicated by the map showing wealth), and this could lead to theft.

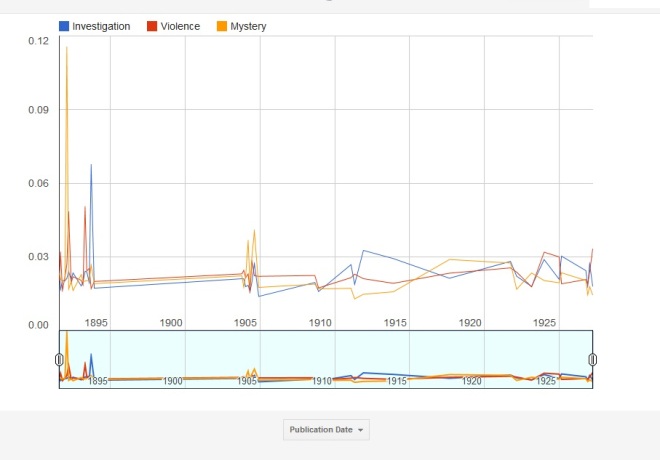

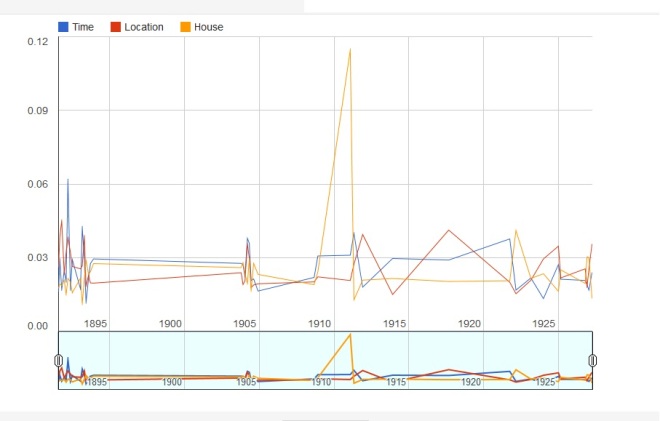

I have chosen abstract topics, which are not too related to History. Nonetheless, I have observed a thematic connection between them, so I divides them into 4 groups.

The related topics of each group show more appearance at the same time periods, suggesting that Arthur Conan Doyle was writing about related themes in each time. Especial concentrations can be seen between 1891-1893, and 1904-1905. After 1908, the release of stories had been constant till the 1920s.

In February 1892, we can see the greatest peak of the whole graph related to the topic “mystery”. This was the release date of The Speckled Band, a story full of words related to mystery, as our class well knows. The peak of “violence” (April 21, 1893), is the release date of The Gloria Scott, a story that ends with a death, which related words are within the “violence” topic. The peak of investigation (September 16, 1893) is related to the story The Greek Interpreter, which involves kidnapping and intimidation, which are material for “investigation”. “Mystery” seems to be the most important topic in the 1904 eight stories, as it stands out from the other topics.

The greatest data here are the peaks of “Time”, in March 16, 1892 – release of The Adventure of the Engineer’s Thumb – and “House” in February 1, 1911 – release of “The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax”. The first, happens over the summer (time aspect), and the second involves a pursuit along housing environments.

The principal trends in this graph are a great peak of Relationship in September 1, 1891 (A case of Identity, a story about marriage and the relationship between stepdaugther-stepfather) and a growing appearance of “Conversation” matters in the stories between 1893 and 1903.

I have chosen to leave the most different topic one alone in the forth graph. It is “Sitting”, which includes words such as “chair sat room fire bell laid asked lit lamp”.

The first peak is related to the story The Boscombe Valley mystery (October 16, 1891), which involves traveling by train, carriage, driving, actions that might involve terms around “Sitting”. The second peak coincides with The Adventure of Wisteria Lodge (September, 1908), a story that happens inside a house (so it has related terms to “Sitting”).

All the charts in:

https://www.google.com/fusiontables/DataSource?docid=1ufgEjCptMHdlZwv27O3SJHmlyex_8CcmCwR3NSIe

In Sir Aurthur Conan Doyle’s short story, A Case of Identity, Sherlock Holmes mentions Leadenhall Street. For this particular case, Holmes helps a woman who claims that her fiancé has disappeared. In order to figure out this mystery, Holmes questions the woman, Miss Sutherland, about her fiancé, Mr. Hosmer Angel. She recounts to him how they met and their correspondence afterword. However, not much is known about the mysterious Mr. Hosmer Angel and where he lived, except that he seemed to take up residence on Leadenhall Street. Miss Sutherland, had been exchanging letters with Mr. Angel, but did not know where he lived, only that it was somewhere on Leadenhall Street.

According to “British Histories”, Leadenhall Street was the home to the India House, which was the location of the East India Company. Although histories do not know where the first East India Company first transacted their business, it is assumed that after the Great Fire in London the India House was placed in Leadenhall Street. Originally the home of Sir William Craven of Kensington, in the year 1701, it is believed that he leased to the Company his large home in Leadenhall Street (Thornbury). The East India House was sold in 1861, and then torn down in 1862. For A Case of Identity, Mr. Windibank, who is discovered to by Mr. Angel in disguise, was a wine importer. The East India Company was a trade company, so it is interesting that Mr. Windibank, a wine importer, would be having his letters be mailed to Leadenhall Street, the location for a highly important trade company. Although Miss Sutherland claims there is a Leadenhall Street Post Office, I could not find any mention of one in my research.

The original Leadenhall Market was also located on Leadenhall Street. It was originally a mansion that was owned by Sir Hugh Neville in 1309, and later was converted into a granary, and then a market for the City by Sir Simon Eyre, a draper and Lord Mayor of London in 1445. Interestingly, on “Charles Booth Online Archive”, Leadenhall Market appeared to be located in a very poverty stricken area.

An old church, called St. Andrew Undershaft is located on Leadenhall Street as well. This church could be found nearly opposite the site of the old East India House. One of the most interesting churches in London, Sr. Andrew Undershaft was named from “‘a high or long shaft or Maypole higher than the church steeple’ (hence under shaft), which used, early in the morning of May Day, the great spring festival of merry England, to be set up and hung with flowers opposite the south door of St. Andrew’s” (Thornbury).

Even today, Leadenhally Street has many important and major headquarters for many companies. Leadenhall has a lot of history, and many distinct and interesting facts can be found about it. In this post, I hope I pointed out some of the more significant and famous facts about Leadenhall.

Fun Fact: In 1803, found across the street from the East India House was the “most magnificent Roman tessellated pavement yet discovered in London” (Thornbury). A “tessellated pavement” is a floor covered in mosaic designs. Laying nine and a half feet below the street, the third side had unfortunately been cut away for a sewer. The mosaic had Bacchus riding a tiger placed in the center with three borders circling him; these borders were serpents, cornucopia, and squares diagonally concave. Drinking cups and plants were found at the angles, and surrounding the whole piece of art was a square border of a bandeau of oak, lozenge figures, true lover’s knots, and on the outer margin plain red tiles. Unfortunately, many pieces of this mosaic were unsalvageable, as owners allowed pieces of it to be stored in open air, deteriorating them. The image below is what has managed to be resorted (British Museum).

Works Cited

“Leadenhall Market.” Charles Booth Online Archive: Booth Poverty Map. London School of Economics and Political Science. Web. 9 November 2014.

Thornbury, Walter. ‘Leadenhall Street and the Old East India House’ Old and New London: Volume 2. British Histories, 1878. Web. 9 November 2014.

“The Leadenhall Street Mosaic”. Roman Britain, 1st or 2nd century AD Found in Leadenhall Street, London (1803). British Museum. Trustee of the British Museum. Web. 9 November 2014.

I used the visualization tool Voyant in order to create a World Cloud for the Sherlock Homes short story, A Case of Identity.

Since it is known that the World Cloud is a visualization of a Sherlock Holmes story, I added “Holmes” to the list of stop words, as well as “said.” These words, though used the most often, were irrelevant to the real analysis of the World Cloud.

Though little can be told about the plot of A Case of Identity from this visualization alone, it helps in pointing out who the story mainly revolves around. The words “Hosmer,” “Windibank,” and “Angel” appear 23, 20, and 19 times respectively throughout the text. Readers could infer that these are the main characters and upon reading the full text would discover that “Hosmer Angel” and “Windibank” are actually the same person.

Next to “Holmes,” which appeared 28 times in the text and was deleted from the Word Cloud, the next most often used word was “little.” This was surprising, as having read the text before creating this visualization, the word “little” seems to have nothing at all to do with the plot of the story. Upon further analysis, however, it can be seen that “little,” though not dealing much with the plot, is always used for a particular reason. Often times, it is used to describe Miss Mary Sutherland. Since she is a woman, she is portrayed as being more dainty, and therefore things about her are little, from her “little problem” to her “little handkerchief.” Watson also uses this term to describe Miss Sutherland’s appearance when Holmes asks him too, pointing out the “little black jet ornaments” on her jacket and the “little purple plush” on her dress. Holmes even goes as far as to comment on her “little income.” This use of the world little to describe Miss Mary Sutherland can be interpreted as a way to show readers that though it’s Miss Sutherland’s case that needs solving, Sherlock sees her as just another woman with a “little” and “trite” problem, and therefore, readers should see her this way as well.

While the comments Sherlock sometimes makes can be viewed undoubtedly sexist, I also think it’s important to look at the context of these stories. When Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote them, this generalization and view of women was the norm. It is only now, reading these stories in the 21st century, that we can point out what it is wrong with some comments made. Back then, this kind of description of women was not seen as an issue. It’s interesting to think, if Word Clouds were used long ago, if the same amount of analysis would be put into the word “little” or even how women were depicted in these Sherlock Holmes’ adventure stories at all.