https://www.google.com/fusiontables/DataSource?docid=1jNGQNPrwU-j8oWzP-gU5fKlYIC9CWThhZDruIx29

Google Spreadsheet Info

Cards

map locations of videos

Pie graph

Bar graph

Donut graph

https://www.google.com/fusiontables/DataSource?docid=1jNGQNPrwU-j8oWzP-gU5fKlYIC9CWThhZDruIx29

Google Spreadsheet Info

Cards

map locations of videos

Pie graph

Bar graph

Donut graph

Finding 19th century pieces of literature was a lot more difficult than I thought upon beginning this task. It took me a few days to find something, but then I came across Lady of the Tiger. The first seven pages involve multiple different types of marginalia ranging from underlining, to circling, to defining, and to annotating. For the purpose of the assignment I will be ignoring the marginalia written in ink because it does not date back pre-1923. On the first page there are quite a few notes in the margins and circled words with synonyms or definitions above them. The circled words with definitions beside them make me think that the reader could have been a student like me, or a non-native speaker who is simply trying to get more acquainted with the language. The reader also underlined important character traits and facts about events happening in the story rather than stylistic details. They might have been an amateur reader or perhaps knew exactly the information they needed for whatever the novel was being read for. For a collegiate level paper, a professor would be looking for more than just a summary of a novel, however. They would rather appreciate a paper geared toward how the author writes and how they portray the information underlined. So perhaps, if they were hypothetically a student, they would be at a lower level in their schooling than the college level. One note does however say “choice of language” on page 3 in regards to the first paragraph of that page. So the reader might have a higher set of critical and analytical skills than previously thought. Their thought process is really exposed though towards the middle of the same page when the reader talks of comparing and contrasting love and jealousy. The marginalia in the book I selected really gives us some insight into the mind of one individual of the Victorian Era.

When I first entered the library, I had certain kinds of books in mind when I entered the library that I wanted to begin my search in. As soon as we got into the library I decided to enter the first stack I saw just to get a feel for what kind of books I would have the best luck with. I opened book after book that appeared to be rebound. I figured the ones with the most use were the ones that were rebound and therefore I would have luck finding marginalia. I got lost in the books, I lost track of time. I was thinking about how so many other people have touched these books for so many different reasons. I felt like I was entering another world. I must have opened over 50 books, even after I found a promising lead with marginalia that appeared to be from the 19th century. There was so much writing in this book, I could tell the person reading it had poured through the pages, looking for meaning in each word. The book I found contained plays from the 19th Century, all written in German. The author was Thomas Moody Campbell. According to the Chicago Tribune, he taught at a Florida State University for 30 years. He passed away of a heart attack at the age of 57. The book was dedicated to his Wife, Annie Pauline Von Klemmen. All of the marginalia I found is written in German, so there isn’t much I can say about the words themselves. I found marginalia on many of the pages, but the ones with the most writing were on pages in the 70’s. The marginalia is found on so many of the pages and even if there are no words on some pages, the owner often underlined and circled things.

Atypical “Attitudes Towards Prostitution”

A practice many would think is far beyond moral taboo for 19th Century London women actually received varying views. One anomalous opinion was written in The London Times in 1858 which expressed that call girls of the day were merely “practising their trade, either as the entire or partial means of their subsistence.” This writer views prostitution as any other occupation, which is fascinating for a time when women weren’t technically even ‘supposed’ to have jobs. The notion that women who practice prostitution are morally wicked is another common view not held by this author. He writes, “they have their virtues, like others; they are good daughters, good sisters, and friends.” In short, the author sees prostitution as a job like any other, one in which a woman can find not only means for subsistence but she can find success.

“Causes of Prostitution”

Another article published in The London Times is written from a different and woman’s perspective. This one was written by a woman who feels unsettled with the limitations on which women can know or offer suggestion about a troubling occurrence in a society. That a woman should not only stray from the practice but not even acknowledge such a topic, for she should not know of such things, that she should ignore and not ask questions: “We have been told heretofore by men whom we respect that it becomes a woman to be absolutely silent on such revolting topics – to ignore, or rather to affect to ignore, such a ‘state of things’ as you allude.” In this passage, prostitutes are referred to (by the woman) “outcasts of our own sex.” All other women are referred to as “virtuous women”, and the writer refers to herself as the latter. The writer sees this topic as one that affects all members of the gender and seems to be deeply concerned. Her view is probably leaning towards the typical view of the time, because she thinks of them as “wretches whose sole and profitable occupation is to hunt down and ensnare victims…” Men are referred to as ‘victims’ of prostitution. So the woman conforms to the gender norms in society that everything morally incorrect is at the fault of women more than at the fault of men, though both deserve equal blame (Adam and Eve and the Forbidden Fruit being the prime example. She even mentions the Bible and Christianity a couple times in her ramble.)

Summary

We have two opinions, one ironically written by a man with outlandish views and one by a woman who conforms to what was seen as acceptable in her society. The articles in this section all prove the idea discussed in class that the issues and topics of Victorian times are virtually no different than those of modern times.

– Miranda Delancey, Online Assignment #1

Design

Time and time again, clean, organized, aesthetic design and visuals on turn up as key to any Digital Humanities project we have done in class so far. For example, GIS mapping projects should not have all of its data sets appear simultaneously, and should give the viewer the option to toggle on/off individual data sets. In the case of Digital Archives, once again, choice of colors and images used on the home page can have a substantial impact on how the user may come to understand what the theme binds together the information in that particular archive.

Scholarly

This quality is what separates reliable DH projects and questionable ones. All the information used in any particular project should be traceable to their original source, whether it be primary or secondary, especially if the information used did not belong to the makers of the DH Project. On a Digital Archive, this would appear perhaps at the end of each object page or whenever a reference to information that was obtained outside the DH project itself.

User Friendly

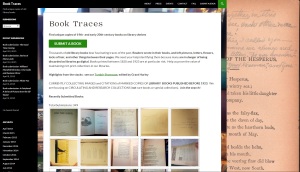

Considering that every individual who makes or uses a DH project are not from computer science disciplines themselves, navigating these projects should feel “organic” or fairly easy to learn. Book Traces is one example of such, where the form to fill out the book submission is extremely easy to understand, and even provides an example on the side.

Interactive

On of the advantages of a DH project over physical paper representations of it, is that the user is able to interact with the project by manipulating when certain bits of data or information are shown at a time. The overlay feature of GIS mapping projects is one example of this, or clicking on a pin to reveal more information about that location is another. A not so good example of this would be the maps shown on the “Art in the Blood” fan project.

Collaborative

Last, but not least, DH projects allow for extensive amounts of collaboration with individuals who need not presently be there to do so. So as long as he or she may have access to the tools online needed to make the project, any person can continue on another’s work so as long the project is open to the public. Again, Book Traces is an elegant example of this as contributing to the project’s storehouse of 19th century Marginalia is quick, but thorough.

Over the course of the semester, we have learned many ways to make a successful Digital Humanities project. I’ve listed 5 of the most important ways below.

1. Good Design

One of the first things a good Digital Humanities project needs is a good design. Having a visually appealing website helps to attract more users and makes for a much better overall experience. It is important to think about choice of colors, fonts, sizes, and placement of your content so that is easy to find and use without being too distracting or difficult for the user. Having lots of photos also helps people who are visual learners to understand the information.

2. Easy to Navigate

Having a good design to your project helps for it to be more user-friendly. The information must be displayed and organized in a way that makes everything easy and simple for the user to find in order to get the most information and use out of it. Having a key that explains graphs and maps is a must because it helps users to fully grasp what they are looking at. Many of the sites we have seen in class have had easily accessible tabs on the side of the project that help you navigate through the site and find everything you need.

3. Interactivity

Having a website where users get to interact with the content is very important. It keeps them interested and more motivated to use it. For example, on the London Gallery Project, they included an interactive map where you could navigate and find art galleries that came around during the 19th century. By clicking different categories, you can press play on the timeline and see the art galleries come up on the map. It makes it more interesting to see the information and easier for users to understand.

Sometimes a Digital Humanities project requires the help of the masses in order. For example, Book Traces is a site that collects submissions of pictures of 19th and early 20th century books that have marginalia pertaining to that time in them in order to learn more about the people and the culture of that time. Over 350 people from all around have submitted their pictures with books they found that contain marginalia. It makes it easier to obtain information for a project and it helps to obtain information that you may not have been able to get access to without the help of others.

5. Have Context/Citations For All Data

5. Have Context/Citations For All Data

It is very important to have proper citation for all of your information if it is not your own. You should try to keep much of the information your own, but if you use someone else’s it must be properly cited to save you from trouble with plagiarism. Having proper context for all of your information is a must as well. If you have a picture or graph without stating what it is or why it’s in your project, it will make users confused and not sure as to why it’s there, which would probably turn them off from the project. For example, on the Art In The Blood website, most of the information is very hard to grasp, but the maps and pictures they show have little or no context to them, so you don’t know why they correlate to each other or why they’re there.

Digital Humanities projects allow scholars to ask new questions because they introduce people to new topics and information that they may have never been introduced to before. Many of the sites we’ve looked at in class are very specific, so seeing something might spark someone’s interest and allow them to do research on that topic and solve new questions. Digital Humanities brings together information in a way that’s relevant to our time and the technology we use, and helps to open our minds to questions we haven’t thought of before.

Digital Humanities projects allow scholars to ask new questions because they introduce people to new topics and information that they may have never been introduced to before. Many of the sites we’ve looked at in class are very specific, so seeing something might spark someone’s interest and allow them to do research on that topic and solve new questions. Digital Humanities brings together information in a way that’s relevant to our time and the technology we use, and helps to open our minds to questions we haven’t thought of before.

Click here to see our mapping project for A Case Of Identity!!

-Christine, Emily, Hannah

A good DH project must presents some features, as we have discussed through this course. I have selected five from these important qualities:

1) Built in collaboration

A good DH project is “open-ended”, which means, a lot of scholars or regular people can contribute adding material. Book Traces is a good example. You can easily submit a 19th century book, which contains something on its “marginalia” or objects inside. It is interesting because it is a collective effort to preserve endangered books, which can be discarded by libraries or disintegrated by the time.

This feature makes the project more effective, because its resources can grow in number and quality faster, as a lot of people are helping.

Collaboration also allows scholars to publish their work before finishing it, so they can get feedback from the audience, from other scholars and, then, improve their work. These “work in progress” was really difficult when the projects were paper-based.

2) Be Scholarly developed and oriented to scholars

Being a scholarly project means that it has been built based on reliable sources and that the project cites those sources properly. Projects which are developed by Universities or Research Institutes are scholarly. However, everyone can build a scholarly project, if he/she is concerned where he/she gets the data and how he/she cites where it came from.

The Rossetti Archive is a good example of a scholarly project. It has been developed as a basis for the project NINES (Network Infrastructure for Nineteenth-century Electronic Scholarship), which demonstrates that it is built towards scholarly purposes. As it is stated on the website, “the Archive provides students and scholars with access to all of DGR’s pictorial and textual works and to a large contextual corpus of materials(…)” – (The Rossetti Archive, section Home).

3) Integration

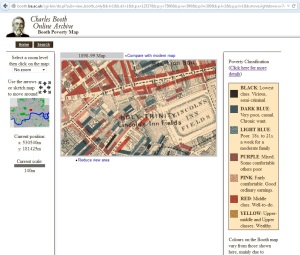

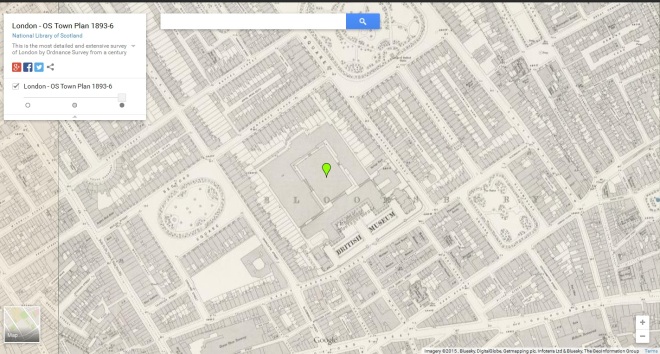

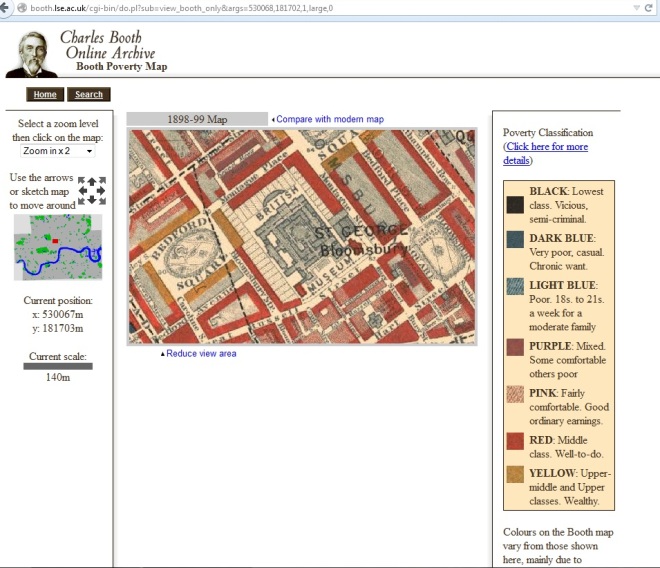

Good DH projects gather a number of objects, maps or even scholarly texts into a single digital interface. This characteristic makes them useful as a scholar or a student can find plenty of information in the same place. Moreover, the digital platforms make possible to conjugate several levels of information onto the same visualization, which would be confusing using printed materials. This is the case of Locating London’s Past, which put together 24 printed maps. Charles Booth Archive is another example. Different colors represent each kind of information, such as crime’s incidence and population through region.

Good DH projects gather a number of objects, maps or even scholarly texts into a single digital interface. This characteristic makes them useful as a scholar or a student can find plenty of information in the same place. Moreover, the digital platforms make possible to conjugate several levels of information onto the same visualization, which would be confusing using printed materials. This is the case of Locating London’s Past, which put together 24 printed maps. Charles Booth Archive is another example. Different colors represent each kind of information, such as crime’s incidence and population through region.

4) Be user-friendly

A good DH project is concerned about how is it easy to a user to figure out by him/herself how the platform works. Being user-friendly involves displaying the information on the screen in an easy way to read and find the data the user is looking for. Locating London’s Past really fulfills this expectation. Besides using design resources to display the information in a clear and readable way, they offer tutorial videos. Besides that, all the tabs follows a coherent organization.  At the top of the page, the user find the two ways of researching – directly onto the map or looking for specific data. Since he decides for data, all the data sets will show up on the left side and the user can pick one up and fill the blanks to find the information he wants.

At the top of the page, the user find the two ways of researching – directly onto the map or looking for specific data. Since he decides for data, all the data sets will show up on the left side and the user can pick one up and fill the blanks to find the information he wants.

Thus, part of being user-friendly is presenting the next DH project’s quality – Design.

5) Design

As the article Radiant Textuality explains, “computerization not only vastly increases the amount of accessible information, it enables much greater flexibility in the ways information can be shaped, scaled, and negotiated” (p. 385). Then, a good DH project takes advantage of the design resources to be good-looking, which makes it attractive to the user as well as user-friendly. Using design properly means doing smart choices of colors, different font types and font sizes to organize and categorize different kinds and levels of information. As the image on the right shows, Locating London’s Past is really successful in using design skills. We can identify the use of the variety of font sizes, and a use of colors that is related to the English flag.

As the article Radiant Textuality explains, “computerization not only vastly increases the amount of accessible information, it enables much greater flexibility in the ways information can be shaped, scaled, and negotiated” (p. 385). Then, a good DH project takes advantage of the design resources to be good-looking, which makes it attractive to the user as well as user-friendly. Using design properly means doing smart choices of colors, different font types and font sizes to organize and categorize different kinds and levels of information. As the image on the right shows, Locating London’s Past is really successful in using design skills. We can identify the use of the variety of font sizes, and a use of colors that is related to the English flag.

On the other hand, the archive Sherlockian.net has a lot to improve concerning to design. The use of colors doesn’t seem to have a purpose. The yellow background and the small font type, as well as the organization of tabs and objects is not very readable and doesn’t attract the user. The links are presented in the regular blue color, which also badly affects the whole appearance of the website.

How DH lets scholars ask new questions?

Through DH, scholarly work can be preserved and self-integrated much better than on paper-based instruments. As Jerome McGann affirms in Radiant Textuality, now it is possible to “integrate the resources of all libraries, museums, and archives and make those resources available to all persons no matter where they reside physically” (p. 381). He adds that “electronic publishing permits scholars to present their work in far greater depth and diversity. Essays can present all their documentary evidence as part of their argument (in notes and appendices, or in electronic links to the original documents). They can also exploit fully the use of illustrations and images, including video film clips, as well as audio clips” (p. 384).

Therefore, DH brings up new issues, that couldn’t be seen without the new technologies such as maps, graphics and visualizations. Scholars and students start to search and identify patterns between data, which was really difficult to do with paper based documents. We didn’t have everything together, online, available to access from any place in the world. Now we can compare information at the same screen, and ask questions about what they signify, which trends we can distinguish. Technologies such as N-grams enable us to exercise these skills of discerning trends and patterns. DH projects can function as a beginning of a research, as we discover some data and start looking for the meaning of it.

Furthermore, digital platforms are available to a broader audience and enable critics to dialogue, as well (p. 387). Thus, scholars can discuss and bring different points of view about some data, which means that DH permits scholars to ask new questions.

The British Museum is mentioned in the story The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle when Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson are asking the owner of the stolen goose about the place he had bought it. Mr. Baker explains that he is a member of a “goose club”, in which each affiliate would receive a goose at Christmas, after contributing with a small amount of money during the year. Mr. Baker says: “There is a few of us who frequent the Alpha Inn, near the museum – we are to be found in the museum itself during the day, you understand” (in The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle, p. 5; Arthur Conan Doyle).

The British Museum is mentioned in the story The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle when Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson are asking the owner of the stolen goose about the place he had bought it. Mr. Baker explains that he is a member of a “goose club”, in which each affiliate would receive a goose at Christmas, after contributing with a small amount of money during the year. Mr. Baker says: “There is a few of us who frequent the Alpha Inn, near the museum – we are to be found in the museum itself during the day, you understand” (in The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle, p. 5; Arthur Conan Doyle).

I have found this specific quotation very interesting, giving concern to what I have discovered about the place in The Booth Poverty Map. It tells us that the area surrounding the British Museum was not that poor. As the map key assigns, the colors shown around the museum correspond to “Middle class. Well-to-do” populations, some wealthy people from “Upper-middle and Upper classes”. People with “good ordinary earnings”, in a “fairly comfortable” situation also used to live in that area (in Booth Poverty Map, Charles Both Online Archive).

However, if we use the arrows resource to search about the surrounding area, the frame changes. Especially if we go to the north-east, south-east or south-west directions, we find dark and light blue patterns, as the image bellow shows. As the key explains, these colors correspond to “very poor, casual, chronic want situations” (dark blue) and “poor who earned “18s to 21s a week for a moderate family” (Booth Poverty Map, Charles Both Online Archive). However, we can still see significant presence of middle-class families in that area, which suggests that people with really different life styles lived together in the same place. Today it is very unlikely to happen, due to the financial speculation.

However, if we use the arrows resource to search about the surrounding area, the frame changes. Especially if we go to the north-east, south-east or south-west directions, we find dark and light blue patterns, as the image bellow shows. As the key explains, these colors correspond to “very poor, casual, chronic want situations” (dark blue) and “poor who earned “18s to 21s a week for a moderate family” (Booth Poverty Map, Charles Both Online Archive). However, we can still see significant presence of middle-class families in that area, which suggests that people with really different life styles lived together in the same place. Today it is very unlikely to happen, due to the financial speculation.

Combining these two data, I could suggest a reason for the appearance of the British Museum in the story and for Mr. Baker’s sentence as well. As Holmes has deduced from the hat, Mr. Baker is an intellectual middle-class men even though he is probably running into financial difficulties at the moment. As he is an intellectual middle-class men, it is coherent that he frequents the Museum and the surroundings. However, he remarked that “we are to be found in the museum itself during the day, you understand” (in The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle, p. 5; Arthur Conan Doyle). I had come up with a possible reason for this statement. Even though the area is populated by middle and upper class families, it doesn’t mean that it is safe. Maybe, during the night, the area was occupied by criminals.

Indeed, some crimes used to happen in the area at night. I have found the case of a theft on George Street, located in the same parish where is the British Museum – Bloomsbury. Coincidentally, this is a case of a hat stealing, that happened in 1819. Both victim and defendant were males. You can see the description of the theft on the image bellow. It tells the details of the action, which is particularly interesting. (from Old Bailey Proceedings data set, at Locating London’s Past)

In addition a curiosity about the British Museum: some renowned names used to frequent the Museum’s Library and the reading room: “Sir James Mackintosh, Sir Walter Scott, Charles Lamb, Washington Irving, William Godwin, Dean Milman, Leigh Hunt, Hallam, Macaulay, Grote, Tom Campbell, Sir E. Bulwer Lytton, Edward Jesse, Charles Dickens, Douglas Jerrold, Thackeray, Shirley Brooks, Mark Lemon, and Count Stuart d’Albany” (in Old and New London: Volume 4, The British Museum part 1 of 2, Chapter XXXIX).

In Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes short story, Scandal in Bohemia, Holmes and company have discovered Irene Adler has eluded them after a servant has informed them of her departure for a 5:15 train at Charing Cross. The station itself, is located on a fairly large road known as, “The Strand”.