Being that Google Ngrams works with only the books that are on Google Books, it was of interest to see what results would the tool would provide should another language be used. Switching the settings of the search to Google’s French corpus, the three words, “liberté,” “égalité,” and “fraternité” were searched together as a point of departure. The three words make up the national slogan of France (liberty, equality, brotherhood), with strong associations to the French Revolution.

French history displays several iterations of leaders and types of government, beginning with the overthrow of the Monarchy. Tracking the words from 1700 to 1900, “liberté” has remained the most used by a wide margin, with “égalité” and “fraternité” remaining much closer to one another. For a long while, “fraternité” hardly shows up at all. Around 1740, “liberté” and “égalité” begin to augment in usage, though “égalité” peters out without a huge amount of growth, while “liberté” continues it’s first large assent until about 1766. This initial breakout shows the impact of the period of the enlightenment in France, with writers discussing essential freedoms, such as person freedom, freedom of thought, and freedom of expression. Jean-Jacques Rousseau in particular had affirmed that all were born free and equal in rights.

Still under the Monarchy, “liberté” remains in descent until the death of Louis XV and thus, the crowning of Louis XVI in 1774 — the last king of the ancient regime. “Liberté” witnesses the beginning of a small increase in usage after 1776, where France’s involvement helping to fight the English during the American Revolution impacted their own views of government. Then, from 1784 – 1792, all three see a significant jump, with that of “liberté” being the largest of all. During this time frame, France saw the Storming of Bastille in 1789, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen by l’Assemblée Nationale and the March on Versailles in 1789. The suspension of the king by l’Assemblée then took place in 1790, the proclamation of the Republic in 1792, and the execution of Louis XVI in 1793.

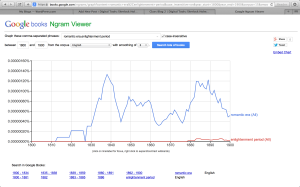

After the fall of the Monarchy, the establishment of the Republic, and the execution of Louis XVI, “liberté” falls tremendously until 1811, where it starts to pick back up again. During this span of time, France saw the First Republic, the Directory, and the Consulate. Ngrams can show the frequency of leaders during these periods of government as well, with compositions giving insight to the Directory, where power was shared between several men.

In 1811, when “liberté” becomes increasingly used once again, Napoleon I began to expand his empire by placing members of his family in rule of various European states. The word goes in waves of usage as France swings from the Empire, to the Restoration, the Monarchy (again), the Second Republic, the Second Empire, and finally the Third Republic in 1871. After this, the use of the word begins to average out, remaining prevalent but not appearing in series of staccato bursts.

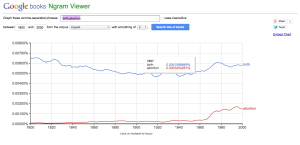

Through Ngrams, it’s possible to see not only a timeline of historic events, as with the rumblings leading up to different parts within the French Revolution, but how they compare with those in other countries. The French Revolution had been in part inspired by the role France played in their assisting the American Revolution. Delving into more in depth functions of Ngrams, it’s possible to access different corpuses of text. Comparing the English and French words for “revolution,” and “liberty,” it’s observable how each term manifested itself. In both languages, “liberty” trumps revolution, and “liberté” remains more frequent than “liberty” save for a short spell from 1808 – 1810.

The richness of the insight Ngrams has provided is lost without historical context. In this case, the combination yields a richer understanding of the French Revolution, how it changed through time, and the intensity of similar words being used in other nations. Revealing curious intersecting paths over time, Ngrams effectively provokes further queries.

— Megan Doty