Class Blog 1

Juxta Editions: The Adventure of the Speckled Band

Juxta Editions

Juxta Editions, The Adventure of the Engineer’s Thumb

http://sites.juxtaeditions.com/engineersthumb

Juxta Editions

My edition of the Sherlock Holmes story, The Mystery of Boscombe Valley:

Japanese Girls and Women with Book Traces

I find the culture of Japan to be very intriguing . When ever I have a chance to learn more about the culture I will accept the opportunity to. I wanted to check out this book for marginalia because this book discusses how the women of that time period were portrayed by the men of the time period.

You can learn a lot of information from the marginalia in this book. I realized that the annotations in this book was more prevalent toward the middle and back of the book. This could mean that the middle of the book and beyond contained more valuable information or it could mean that the reader wasn’t as interested in the beginning of the book as he was in the end of the book. There could be many different reasons for the this annotative pattern. The content of the annotations holds the most value though. There are noticeably two different annotative styles In these photos provided. On page 21 you can notice how the person who annotated put brackets around the paragraph they thought was useful. From page 86 and up you can see how the sentences are underlined and connected with parenthesis instead of brackets.

From the annotations alone I was able to figure out that the Japanese wife, of this time, is responsible for the happiness of her home. Even if her husband is the reason for an unhappy home she would still take the blame. Her duty is to her husband and to her parents-in-law, but her duty is to her parents-in-law before her husband.

A 91 Year Old Message

When we started looking for possible books with marginalia I originally started looking at old books about music. After looking through several books unsuccessfully I decided to move toward the British Literature section of the library. The marginalia I found was located in a Theatre Royal Book on the very first page. The book was clearly a gift from one person to another dated 1923. The message reads:

“To Barry Lufino

[illegible] of a great line

a souvenir

Theare Royal Huddersfield

July 16th 1923

From [illegible]”

I found this interesting because I could’t help but wonder what they story was between these two people. Did the giver of this book go to the theatre alone and bring back a gift for a loved one or did the two people go together? Did they live in Huddersfield or did they travel there? How were these two people related? Family? Friends? Lovers?

The marginalia s also interesting simply because of the fact that the giver wrote a message in the book for the receiver to remember when, where, and who it was from. My grandmother used to write in the books she gave people, but other than her I don’t know anyone else who still writes in books when giving them as a gift. If you are giving someone a book you usually just cross out the price tag and give it to them. The message shows that this person wanted to make this a more intimate gift with a personal message.

The message that was left in this book is important because it is written proof that this book was passed on from person to person. The Huddersfield theatre is in West Yorkshire in England. This book somehow made it from there all the way to SUNY New Paltz and this bit of writing shows a small part of that journey.

Nicholas Nickleby and other Booktraces

When we were given the book traces assignment, I immediately looked for one of my favorite books from the 19th century: The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby by Charles Dickens.

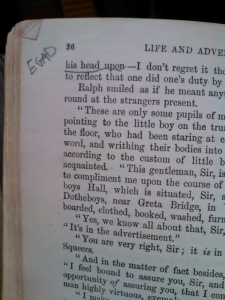

The edition in Sojourner Truth Library was published by Macmillan in 1907. I have to say, I was disappointed not to find more markings in this incredible book, but one marking I found was some underlining and, beside it in pencil, the word “EGAD.” I am assuming this word is a a direct response to the conditions of Dotheboys Hall in the 1800s. Dotheboys is a fictional boarding school that Charles Dickens created as an example to show the public in a more persuasive way that boarding schools are terrible places to send your children. In this example on pages 35 and 36, Dickens paints a picture using the characters’ discussion of the demise of a young boy who only had a dictionary to lay upon. The reader seems to have had a very personal response to this image. This reader’s response is what Dickens was aiming for in the readers of his generation. Though Nicholas Nickleby is a long novel with many themes and subjects, bringing attention to the insufferable boarding schools of the time was very important to Dickens when writing this book. There are many more examples of the conditions in the boarding schools. Perhaps the novel was too long for the reader to continue, or maybe this statement was the first to really show what occurs in these schools and the reader became less sensitive to the images. Either way, I thought this was an amusing reaction to find out of very few other markings in the text.

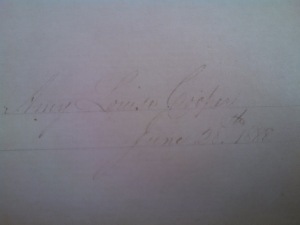

In another book, (I regret to say I didn’t document which – likely because there were no other markings), Amy Louise Cooper signed the flyleaf of the book on June 28th, 1888.

The inscription is barely visible now, but it really makes me wonder how far this book has traveled, and whether it has been read entirely, and, if so, how many times it has been read. A quick Google search of Amy Louise Cooper will bring up quite a few people from the past, but, without a sense of geography, there’s no way of knowing which one this book belonged to.

Searching in the library for book traces was a lot of fun, and I will definitely be looking for more in the future. I really enjoy history when I can interact with it, and seeing the words in the handwriting of previous readers makes reading the novel itself so much more satisfying and interesting. The book traces website is fascinating, and I hope I can contribute more book traces as I find them.

-Brooke Chapman

Book Traces: A Reader’s Understanding of Emerson

After searching for nearly two hours for a book that fit the criteria for this Book Traces project, I was just about ready to give up. Though I had found a lovely poem written in a copy of John Erskine’s ‘Adam and Eve: Though He Knew Better,’ the book was published in 1927; 7 years after the set Book Traces time period.*

However, just as I was about to abandon all hope of finding a book with any traces in it, I found a small book with “Essays” written on the binding in chalk, with “Emerson” written directly below it. The book’s original cover seemed to have been damaged, and so a forest green type of tape was used to repair it, either by the library or by an original owner.

The book of essays was the second of a series and was published in 1900, though the essays it contains – 9 in all, including an Emancipation Address – were all written and published individually much earlier. Some of the essays have minimal markings, while others have an abundance of marginalia. It was interesting to see which essays appealed more to the reader who made these marks, as well as what statements made by Ralph Waldo Emerson left an impact.

The essay I saw that contained the most marginalia was the essay entitled, “Experience.” Many important statements were underlined, and the reader placed check marks and small stars next to passages they probably believed were important. The check marks and stars were interesting to me because it showed me that people in the past studied and took note of the same things I study and take note of. As I read some passages of the essays in order to gain a better understanding and context of it, I found myself going to mark the same statements and passages they had already been marked, simply out of habit.

The most interesting piece of marginalia I found in the “Experience” section of the book was the simple writing of “death of son.” On the previous page, Ralph Waldo Emerson speaks of the death of his son and the grief that accompanies death, but it seemed odd to me that the reader would simply write “death of son,” and that’s it. Did the reader of this series of essays also experience the death of a son? It seems a little far-fetched, but it’s very possible.

Though “Experience” was the essay that was most marked up, several other essays in the small series were also marked. The underlines, checkmarks, and stars remained, but added to those were much more small comments in the margins of the essays. The most interesting thing I found written in the margins was, “Our whole life is but a pursuit,” written on a page of an essay entitled, “Nature.” The statement is found nowhere in the essay but was instead an original statement from the reader. The essay “Nature,” deals with the nature of humans – our drives, desires, hungers, etc – so this statement made by the reader suggests that they truly understand what Emerson is trying to convey.

The marking up of Emerson’s essays shows that whoever read them enjoyed and agreed with the statements he was making. Though Emerson led the Transcendentalist movement in the mid-19th century, the marginalia in these essays shows that his ideas were still widely studied, understood, and spread in the early 20th century.

*Here is a photo of the poem I found. Though it was past the time period we needed, and I didn’t do my blog post on it, Andrew Stauffer asked me to upload it.

Tracing Prussian History

I decided to try and Look for marginalia in Books concerning with Prussian history because I am Prussian and am proud of my heritage. The first piece of marginalia that I found was in a book written in German about Friedrich The II and his rein in Prussia. Though written entirely in German the title is “Aussen und Gedanken, Friedrich von Preussen”, which translates to “Sayings and Thoughs of Friedrich of Prussia” by Frederick. From the marginalia we can see that the person who wrote it was reminding themselves that he was Friedrich The II, because in the title of the boo he is only referred to as Friedrich of Prussia.

Another piece of marginalia was Fining the original call numbers written by a librarian.

(“The Man and the Statesman; being the reflections and reminiscences of Otto prince von Bismarck” by Otto von Bismarck”)

(“The Man and the Statesman; being the reflections and reminiscences of Otto prince von Bismarck” by Otto von Bismarck”)

There were also notes taken like in these Two books where the reader either took notes, underlined words or phrases or possible blacked out a section so that they could use this later when writing or to make it easier to understand and make stronger connections while reading. In the image below from “Frederic the Great” by Thomas Macaulay, the reader underlines words and phrases that have to do with why Prussian invasion of Austrian Selisia and also makes a few side notes on where to use this in their work.

Finally, and most undeniably the coolest thing that I found was in a book called “The House of Hohenzollern” by Hodgetts, where someone had paste sections from a newspaper of the inside cover and on the first binding page. In the Articles it talks about how during the end of world war one when the British and American troops were pushing the German boarders in farther they found the Crown of Frederic the Great and a 15 of his personal snuff boxes and it is dated Jan. 6 – 1946.

post by Josh Wendt