By Beth Wynne, Miranda Delancey, Devon Hauser, Jenna Corti, Danielle Koppie, Veronica Verstraten, and Rachel Janowsky.

Author: wynneb1

Victorian London Locations: Threadneedle Street

Threadneedle Street is mentioned in The Man with the Twisted Lip, where Neville St. Clair, disguised as Hugh Boone, performs his beggary. Boone sits, “Some little distance down Threadneedle Street, upon the left-hand side,” just outside the opium den (Doyle 5). This is where Mrs. St. Clair spots her husband flailing from a window. Before this interruption she walks skeptically, “glancing about in the hope of seeing a cab, as she did not like the neighbourhood in which she found herself” (Doyle 4). The story gives the impression that this was an impoverish and faulty area.

A historical account of Threadneedle St. recalls the area was occupied by “cripples on go-carts who haunted the neighbourhood” (Thornbury, “Threadneedle Street”). This alludes to Doyle’s story quite well considering St. Clair portrayed Boone as a cripple.

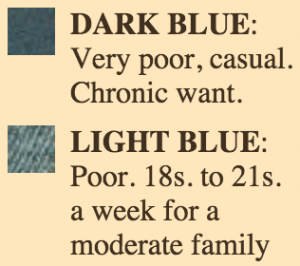

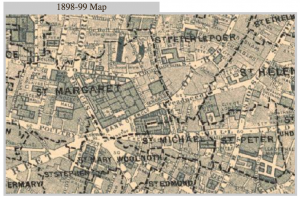

Taken from the “Charles Booth Online Archive,” the area surrounding Threadneedle Street was classified as poor. (See Poverty Classification Key.)

It’s hard to see clearly, but the street is located mid photo, above St. Michael. View the “Booth Archive” page, here.

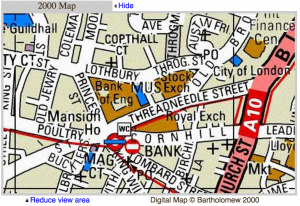

Here’s a better glimpse of Threadneedle Street from 2000.

Here’s a better glimpse of Threadneedle Street from 2000.

The crime and poverty as described in The Twisted Lip and the Poverty Classification (Booth Archive) of Threadneedle St. correspond well.

So, how much crime actually surrounded Threadneedle Street based off of the story in The Twisted Lip? Using “Old Bailey Online,” I was able to find multiple accounts of grand larceny, murder and theft in the Threadneedle St. area. From the Conviction of Henry Harrison, Mr. Harrison, escaped prisoner, hid for sometime in the home of a Mr. Garway. As it is mentioned, “He takes a Lodging at Mr. Garway’s in Threadneedle-street, on the twenty third day of December, and there he continued till about the first of January” (“Henry Harrison, Killing”). Mr. Harrison was a convicted murderer. Pretty profound!

A particular case involved several pieces of stolen clothing by a man named Joseph Johnson, carrying “the Goods of William Savage” from London’s Lombard Street to Threadneedle Street (“Joseph Johnson, Theft”). Other cases involved pickpocketing, and violent encounters. A constable was charged with Edward Lynch, where on “Threadneedle street, [the prisoner] drew a knife upon the prosecutor” and made attempts at the constable as well (“EDWARD LYNCH, Theft”).

Charles Rice, who had stolen innumerable goods, was spotted on Threadneedle Street. Once, by a man named Thomas Edwards who “was coming up Threadneedle-street, when [Rice] was in custody,” and another time by Alexander Barland who saw [Rice] heading towards the “Edinborough coffee-house” (“CHARLES RICE, Theft”).

Edinborough wasn’t the only coffee-house mentioned near Threadneedle St. From “British Histories” I learned of the “North and South American Coffee House (formerly situated in Threadneedle Street)” (Thornbury, “Threadneedle Street”). There was also the Baltic Coffee House, where merchants and brokers occupied their time. It was described as a “rendezvous of tallow, oil, hemp, and seed merchants” (Thornbury, “Threadneedle Street”).

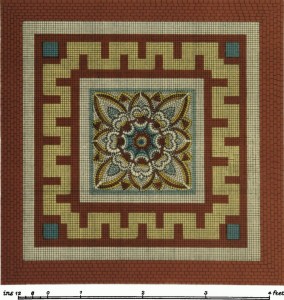

Threadneedle was also the site of the French Protestant Church where red pavement lined the streets. The findings of pavement are rather remarkable and exceptionally crafted (Thornbury, “Threadneedle Street”). It goes to show that Threadneedle St. was not solely defined by theft and poverty but the site of pleasant coffee-houses and decorated pavement.

The Threadneedle Street Pavements:

Works Cited

“Joseph Johnson, Theft, October 1720 (t17201012-3).” Old Bailey Proceedings Online. Web. 6 November 2015. <http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t17201012-3-defend38&div=t17201012-3#highlight>

“Henry Harrison, Killing, April 1692 (t16920406-1).” Old Bailey Proceedings Online. Web. 7 November 2015. <http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t16920406-1&div=t16920406-1&terms=+threadneedle%20+street%20#highlight>

“CHARLES RICE, Theft, September 1785 (t17850914-125).” Old Bailey Proceedings Online. Web. 7 November 2015. <http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t17850914-125&div=t17850914-125&terms=+threadneedle%20+street%20#highlight>

“EDWARD LYNCH, Theft, September 1776 (t17760911-34).” Old Bailey Proceedings Online. Web. 7 November 2015. <http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t17760911-34&div=t17760911-34&terms=+threadneedle%20+street%20#highlight>

Thornbury, Walter. “Threadneedle Street.” Old and New London: Volume 1. London: Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1878. 531-544. British History Online. Web. 7 November 2015. <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/old-new-london/vol1/pp531-544>

“Plate 50: Threadneedle Street, Pavements.” An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in London, Volume 3, Roman London. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1928. 50. British History Online. Web. 5 November 2015. <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/london/vol3/plate-50>

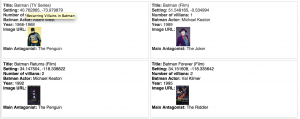

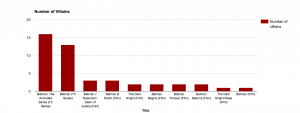

Google Fusion Tables: Batman Portrayals

Essay Video

Here’s a link to my essay video.

https://www.wevideo.com/hub#media/ci/492463889?timelineId=487365025

Google Ngram: Undergarments

I’ve always been intrigued in the history of fashion, especially the amount of layers that were worn in previous centuries. From my understanding, women had a strict form of dress in the 19th century. Had you not worn layers of garment and cloth, you were violating what was deemed socially acceptable. With social acceptance came discomfort, for many of the garments were painful to wear.

I decided to focus on the female undergarment, which was not just an impressionable fashion statement but a social construct used to manipulate what women were expected to look like. I find that these examples truly emulate the saying beauty is pain.

I chose corsets, bustles, and crinolines:

I knew little of the terminology behind 19th century clothing so I researched ’19th century fashion’. The corset, probably the most notable article of the three, was worn consistently throughout the century but in different adaptions. The invention of the steam-moulded corset became popular between 1860-1880, created by Edwin Izod (a big surprise that it was developed by a man) (Victoria and Albert Museum, “Crinolines, Crinolettes, Bustles and Corsets from 1860-80”). The rise of corsets during that interval on the graph is presumed to be because of the steam-moulded corset popularity.

From 1890 and beyond, the percentage for corsets shows an increase. Although the garment was still a social construct, the stiff, discomfort of the corset came into question. After the 1890s, more corsets were made with wool and cotton, adjustable straps, and without whalebone, “a sensible rather than attractive image” (Victoria and Albert Museum, “Corsets and Bustles from 1880-90 – the Move from Over-Structured Opulence to the ‘Healthy Corset'”).

The bustle, which is otherwise known as a tournure, was used as an extension of the skirt to create a full silhouette. The graph shows a fairly steady percentage from 1800-1900. Like the corset, the bustle varied in design throughout the century. In the mid-1800s, the bustle was more plump. By the end of the 19th century, clothing was becoming more slender. Some bustles had trains extending from the dress as part of the fashion. The declination of bustles on the graph could be due to the removal of layers and drapery in fashion (Thomas, “Bustles”).

The crinoline was another garment designed to fill out the dress. The cage crinoline was popularized in “the late 1850s and early 1860s,” but because of difficulty with the spring steel and immobility, the design was no longer favorable (Victoria and Albert Museum, “Corsets & Crinolines in Victorian Fashion”). There is clear indication of this decline around 1865 on the graph.

I wanted to continue with a Victorian England setting, but I was curious what another corpus would show. The German percentages were far more drastic. Bustles showed no popularity, while corsets appear to have had rising popularity in the 1890s and the crinoline shows fluctuation but was not introduced until 1860 on the graph. While I did no research on German garments during this era, I found the differences interesting!

Works Cited:

Thomas, Pauline Weston. ” Bustles.” Bustles. Fashion History. Web. 7 Oct. 2015.

“Crinolines, Crinolettes, Bustles and Corsets from 1860-80.” , Online Museum, Web Team, Webmaster@vam.ac.uk. Victoria and Albert Museum. Web. 7 Oct. 2015.

“Corsets and Bustles from 1880-90 – the Move from Over-Structured Opulence to the ‘Healthy Corset'”, Online Museum, Web Team, Webmaster@vam.ac.uk. Victoria and Albert Museum. Web. 7 Oct. 2015.

“Corsets & Crinolines in Victorian Fashion.” , Online Museum, Web Team, Webmaster@vam.ac.uk. Victoria and Albert Museum. Web. 7 Oct. 2015.

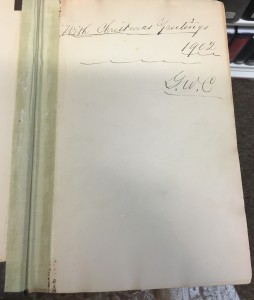

A Holiday Greeting within The Encyclopaedia of Quotations

It had not been long before I discovered a book with marginalia in it. I opened the cover of The Encyclopaedia of Quotations (or rather the complete title: The Encyclopaedia of Quotations; A Treasury of Wisdom Wit Humor Proverbs Etc.) and found distinctive handwriting from the late 19th century. The book was rebound by the library, so I presumed it was authentic and there must be some significance to how much it had been used. Perhaps someone had cherished it enough to constantly fiddle at the cover, or it was simply a factor of old age.

It was written by Adam Wooléyer and published in 1893 in Philadelphia. The cover page revealed beautiful handwriting, which I presume to be either Spencerian or Copperplate. Although it was the only marginalia revealed in the book, it was wonderful to find, and rather endearing. It reads,

“With Christmas Greetings

1902

G.W.C”

I can only assume this book was a gift from one person to another, presumably from a particular “G.W.C.” Based on the book’s title, I like to imagine the person it was gifted to had an adoration for quotations. I imagined this particular G.W.C. writing on a snowy December day to their dear friend with a merry smile upon their face. To my disappointment, there was no marginalia in the rest of the book (which was a fairly big book might I add). The pages were slightly yellowed, presumably from old age. Aside from that, the book was in fair shape without tears or stains.

Though I fell victim to romanticizing the story behind the inked script, I hadn’t discovered any more marginalia throughout my search. The other books I chose from were in similar condition as The Encyclopaedia of Quotations. I did find this assignment to be fascinating. I marveled at how authentic these books appeared on the shelves; their binding was just as captivating. It was equally amazing and puzzling to consider that they weren’t preserved or stored away somewhere. I found myself smiling when I was able to touch the cloth binding, marveling at the torn threads at the top while the pages inside were still perfectly in tact. I was in disbelief that I had access to books from the 18th-19th century that look like age-old relics.

You can view my Book Traces submission here.

Holmes and Music

Researching Victorian London: The Telephone

During the Victorian Era, England experienced an influx of reformations and developments. It was a technological upbringing where communication was blossoming in new and phenomenal ways. “The Victorian Dictionary” by Lee Jackson supplied information on communications in the Victorian Era, particularly the telephone. Women who held jobs as telephone operators worked diligently under strategic rules and etiquette. It was a highly organized occupation. Women received explicit training while attending telephone school where they practiced the skills of answering calls and general communication. While supervised by an experienced operator, women learned how to operate tasks on dummy switchboards and plugs. The training was strategic and complex, the methods of which demonstrated the progressiveness of the Victorian Era. Whilst practicing with fellow operators, the attending supervisor corrected mistakes that were made during practice calls.

Etiquette and decorum was required as a telephone operator. The females had to make physical accommodations to maintain in good health. A company called The Postal Department required each girl be examined by a female physician; her eyes were checked and her teeth were fixed to ensure their would be nothing restricting her from working. They were required to be at least 5 ft. 2 in, “extra lightweights [were] rejected” (Thompson par. 12). They wore graduate gown’s of dark material. A photograph of the Post Office Central Telephone Exchange depicts women communicating on telephones in their drab, dark gowns appearing identical in their disposition and appearance. The Victorian Era woman was expected to appear formal and quaint. In the workplace they were required to wear gloves to “maintain the contour and complexion of their busily worked fingers” (Thompson par. 4).

Aside from the strange requirements of their trade, the female operators experienced rather lavish lives. “Her dining-room, decorated with the flowers she and her comrades have brought from their own gardens, looks like a first-class restaurant and her sumptuous dinner costs her fivepence” (Thompson par. 12)! The advancement of telephone communication during the Victorian Era provided innovation for eras to come.

Beth Wynne’s Introductory Post

Hello DHM293!

My name is Beth Wynne, I am a freshman at SUNY New Paltz, and I am studying as an English major. I’m interested in literature, creative writing and art. I hope to learn an abundance of things from this class.