In The Sherlock Holmes novel, “A Sca ndal in Bohemia”, Charing Cross/Charing Cross Station is merely mentioned in passing and is ultimately where Irene Adler escaped to with her newly wedded husband to some unknown location. In the story, the location has nothing to do with any crimes but it does add to the mystery that is Adler’s character. All in all, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle uses Charing Cross to his advantage in furthering Irene Adler’s elusive character. However, according to Old Bailey Online, an archive of the proceedings of London’s Central Criminal Court, at the time in real life there were many instances of theft/simple larceny. (Oldbailyonline.net)

ndal in Bohemia”, Charing Cross/Charing Cross Station is merely mentioned in passing and is ultimately where Irene Adler escaped to with her newly wedded husband to some unknown location. In the story, the location has nothing to do with any crimes but it does add to the mystery that is Adler’s character. All in all, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle uses Charing Cross to his advantage in furthering Irene Adler’s elusive character. However, according to Old Bailey Online, an archive of the proceedings of London’s Central Criminal Court, at the time in real life there were many instances of theft/simple larceny. (Oldbailyonline.net)

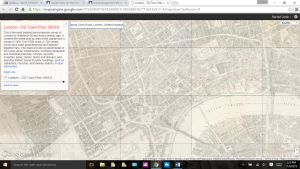

To provide some background into the location, Charing Cross and Charing Cross Station are very close to The West Strand which, according to “The Historical Eye”, “In the e vening, the footpath on the right just outside Charing Cross station is occupied by a more or less regular road of energetic new tenders and somehow, standing here, one feels that one is in touch with the whole civilised world.” However, The West Strand today is described in a much

vening, the footpath on the right just outside Charing Cross station is occupied by a more or less regular road of energetic new tenders and somehow, standing here, one feels that one is in touch with the whole civilised world.” However, The West Strand today is described in a much more negative light, “This part of the Strand is still one of London’s busiest streets, with Charing Cross station disgorging commuters in the morning and hoovering them back up in the evening.” (historicaleye.com)

more negative light, “This part of the Strand is still one of London’s busiest streets, with Charing Cross station disgorging commuters in the morning and hoovering them back up in the evening.” (historicaleye.com)

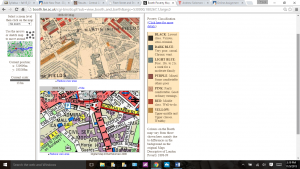

According to the Booth Poverty Map, the residential areas around Charing Cross are all quite wealthy, which i s the case with many of the locations mentioned in “A Scandal in Bohemia”. (booth.lse.ac.uk)

s the case with many of the locations mentioned in “A Scandal in Bohemia”. (booth.lse.ac.uk)

Citations

“Booth Poverty Map & Modern Map (Charles Booth Online Archive).” Booth Poverty Map & Modern Map (Charles Booth Online Archive). N.p., n.d. Web. 09 Nov. 2015.

“The Historical Eye.” Fleet Street and Strand. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 Nov. 2015.

“The Proceedings of the Old Bailey.” Results. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 Nov. 2015.