Here is a link to Ted Underwood’s article, “How not to do things with words.”

In his article “How not to do things with words,” Ted Underwood addresses problems some face while using Google Ngram. He writes that when using Ngrams, we must be aware of certain “methodological pitfalls.” One of these pitfalls is the evolution of words over time. He gives an example of the word ‘leadership.’ Today, one would not describe a leader as someone who is “loud-voiced” because “that’s just rude.” However, Homer describes a loud-voiced man as a good leader because “he can be heard over the din of speakers.”

Taking into consideration what Ted Underwood had to say, I used Google Ngrams to do two searches where each time I compared the prevalence of three different words.

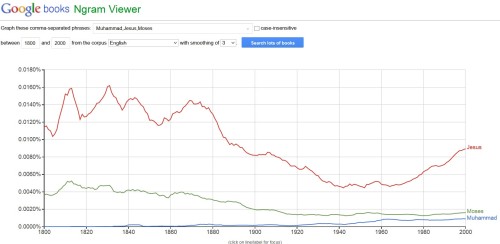

Here, I searched Google Ngram for Muhammad, Jesus, and Moses. It was no surprise that Jesus was a more popular word. This is because, as said in class on Thursday, most books in the canon are written by white males. You can probably add ‘Christian’ to this. The trend shows the word Jesus coming up a lot before the 19th century, then declining from around 1880 to 1970, and increasing from 1970 to the present. In addition to this, there are high points in 1812, 1831, 1843, and around 1870. Off the top of my head, I am not sure what the reason for this is. It is especially surprising seeing the name becoming more prevalent after 1970 since I would think we live in a more secularized society now than we did fifty years ago. The word ‘Moses’ has a similar trend, where it was more prevalent in the 19th century, with a general decline as time passes. Since Moses is an important character in both the Christian and Jewish religions, it would make sense as to why he is as occupant as he is. I’m not sure how many Jewish writers are in the canon of literature from the 19th or 20th centuries, but there must be some; I would think much more so than there are of Muslim writers. This brings me to Muhammad, who really starts off with little to no prevalence until 1920, where he begins to increase. I wouldn’t think you’d find many Muslims in 19th Century Europe. For centuries, the Muslim Moorish Empire ruled Spain, but by the 19th Century, they were well gone. Most Muslims would probably be found in the Middle East and in Africa, which makes me think of one of my favorite novels to come out of Africa, Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe. This was published in the 1960’s, and I would be surprised if it isn’t in the canon of literature. Even though Things Fall Apart is not at all about Muhammad, and Achebe is not Muslim, it is still an important text because it was written by a native born Nigerian in English, and because it was a best seller. With the industrialization of Africa by white Christians well in place by the mid-20th century, I would think that a door would be open to these Africans to have their published writings seen by the Western World. The same goes for India, especially during it’s time of independence from the British.

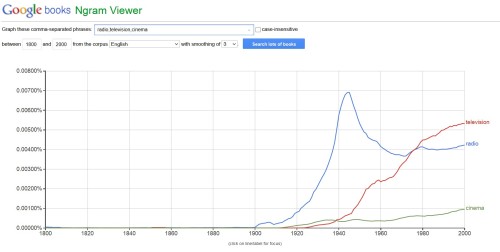

Here, I searched Google Ngram for radio, television, and cinema. Just from looking at the graph, we see that radio is more prevalent until the 1970s, when television takes the lead, with cinema almost always on the bottom. One of the reasons cinema is on the bottom despite the popularity of movies could be the word ‘cinema’ as oppose to the word ‘movie.’ If you were to make another graph where you switch the word ‘cinema’ with the word’ movie’ you would see the ending prevalence to be almost double. There is not much mystery as to the reason for these three words to be more prevalent in some times and less prevalent in others though. The radio was invented in the early 19th century, but it didn’t have a wide-spread popular use until the late 19th century into the early 20th century. The graph shows us ‘radio’ growing more and more prevalent until the 1940’s, where it peaks and starts to decline. ‘Television’ begins to incline starting at around 1920, all the way to 2000 – the same goes for cinema. At around 1975, ‘radio’ and ‘television’ become equal, where afterwards ‘radio’ flattens out while ‘television’ continues to increase. This seems to follow history, where television becomes more popular than radio, while radio is still used. Of course, it’s important to remember that this graph is a representation of words used in a certain group of books, not practical uses of individual devices.

In conclusion, Google Ngrams is a great tool that can create a very helpful and nifty visual. To top it all off, it’s also incredibly user friendly, and requires little effort. Of course you cannot get everything you may need to from Ngrams. For instance, my second graph showed me that radio was always more prevalent than cinema, but it did not tell me why. To figure out why you would have to do independent research. It’s also important to understand that Google Ngrams is not always a safe bet. As Underwood said, you can not always count on getting a reliable graph by simply using a good list of words. So, Ngrams is great, but, like many tools, it is not perfect and absolute.