Bridges in Victorian London were not just a method of travel and a way to improve commerce; they were a path that led to assimilation between the north and south and one of the biggest factors in the expansion of the city. London Bridge itself happens to be almost directly in the center of London and therefore, both auto traffic as well as foot traffic are extremely plentiful. In fact, according to The Victorian Web’s London Bridge section, it states that approximately 22,000 vehicles and 110,000 pedestrians cross the bridge every day.

With the amount of traffic the bridge sees every day and the fact that it is located in the heart of the city, it is not difficult to surmise that there is quite a bit of criminal activity to be found on or near this landmark. When a search is done on the Old Bailey crime website, 102 matches pop up as opposed to the ten that can be found when searching a less treacherous location such as Green Park. Of the 102 matches, 99 of them are theft—most of which are small pickpocketing crimes but still plenty more are much worse. One account told the story of Sarah Arnold and Margret Atkins who were both attacked and carried from the bridge to a nearby tavern, where the attackers told the tavern owner that they were taking the women to a Justice of the Peace for treason. The article also states: “[Mrs. Arnold] declares, that they used her in a very uncivil manner, and gave abundance of ill names.” Now I may be imposing my own modern perspective, but the implications of that sentence seem to point to more than just theft. I personally believe that a lot more than just 102 accounts of criminal activity occurred on this bridge, just not all of it might be written down.

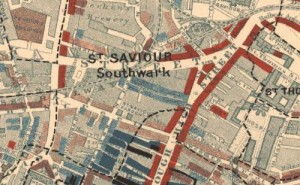

A huge factor in the fact that there is a lot more crime that happens on London Bridge as opposed to other places is the fact that there is a diverse economic standing among the residents that live nearby. As you can see on the map below, Borough High Street—the road just before you would reach London Bridge—is marked red for middle class, well-to-do, and is second on the Booth Poverty website in terms of wealth. Surrounding these wealthy citizens however (shown in light blue, blue, and black respectively), are the poor, the very poor, and the lowest class. The mix of these socioeconomic backgrounds on one main bridge might be the reason so much crime takes place as well as the fact that it is mostly theft.

In “A Lost Masterpiece” the narrator is the picture of conversion from country life to city life—full of optimism for a bright and better future. On their five mile steamboat ride up the Thames from Chelsea to London Bridge, they comment on their surroundings: “The river was wrapped in a delicate grey haze with a golden sub-tone, like a beautiful bright thought struggling for utterance through a mist of obscure words.” Even enveloped by greyness, the narrator still sees a golden hope shining through the fog. Throughout the text, they use words such as “drowned creatures,” “monster chimneys,” “murky depths,” and “hideous green.” Yet in the end they still say, “But what cared I? Was I not happy, absurdly happy?” I think there is a deep naivety in all immigration—be it to a foreign country or just to a city. But just as people from all over the world believe that immigrating to America will open up a new and better life for themselves, moving from country to city is just as much a fantasy. Their steamboat ride symbolizes this move perfectly: riding on a giant piece of industry into the very heart of industry. And perhaps the end of the story is a falling from on high—that in the same way that their bright optimism and inspiration is dashed by a rushing city girl, the hope of a brave new world, a beautiful world, is taken into perspective and mellowed.