The Achilles Statue, or The Wellington Monument, is a bronze statue that rests in Hyde Park, London and was built by Sir Richard Westmacott in 1822. According to British History Online, its construction was subscribed by the ladies of England as a monument in honor of the Duke of Wellington and his military successes. It was received with a lot of controversy because it was the first nude statue to be put on public display in London. The statue features an entirely nude Achilles (save for a single olive leaf over his family jewels), his armor next to him, and his sword raised in the air preparing to strike. A writer of the Tour of a Foreigner in England wrote, “His [Westmacott’s] ‘Achilles,’ which has been erected as a monument to the Duke of Wellington, is merely a colossal Adonis.” Adonis is another character in Greek mythology, often used to describe handsome young men; he is a vegetation god that is eternally youthful and beautiful as well as a deity for life, death, and rebirth. I think the statement that Westmacott’s Achilles looks more like Adonis is fair, but this shouldn’t mean that Achilles wasn’t also a beautiful man–he was able to disguise himself as a girl on the island of Scyros. I think both Adonis and Achilles fall under the criteria of “pretty boys”.

The Achilles Statue, or The Wellington Monument, is a bronze statue that rests in Hyde Park, London and was built by Sir Richard Westmacott in 1822. According to British History Online, its construction was subscribed by the ladies of England as a monument in honor of the Duke of Wellington and his military successes. It was received with a lot of controversy because it was the first nude statue to be put on public display in London. The statue features an entirely nude Achilles (save for a single olive leaf over his family jewels), his armor next to him, and his sword raised in the air preparing to strike. A writer of the Tour of a Foreigner in England wrote, “His [Westmacott’s] ‘Achilles,’ which has been erected as a monument to the Duke of Wellington, is merely a colossal Adonis.” Adonis is another character in Greek mythology, often used to describe handsome young men; he is a vegetation god that is eternally youthful and beautiful as well as a deity for life, death, and rebirth. I think the statement that Westmacott’s Achilles looks more like Adonis is fair, but this shouldn’t mean that Achilles wasn’t also a beautiful man–he was able to disguise himself as a girl on the island of Scyros. I think both Adonis and Achilles fall under the criteria of “pretty boys”.

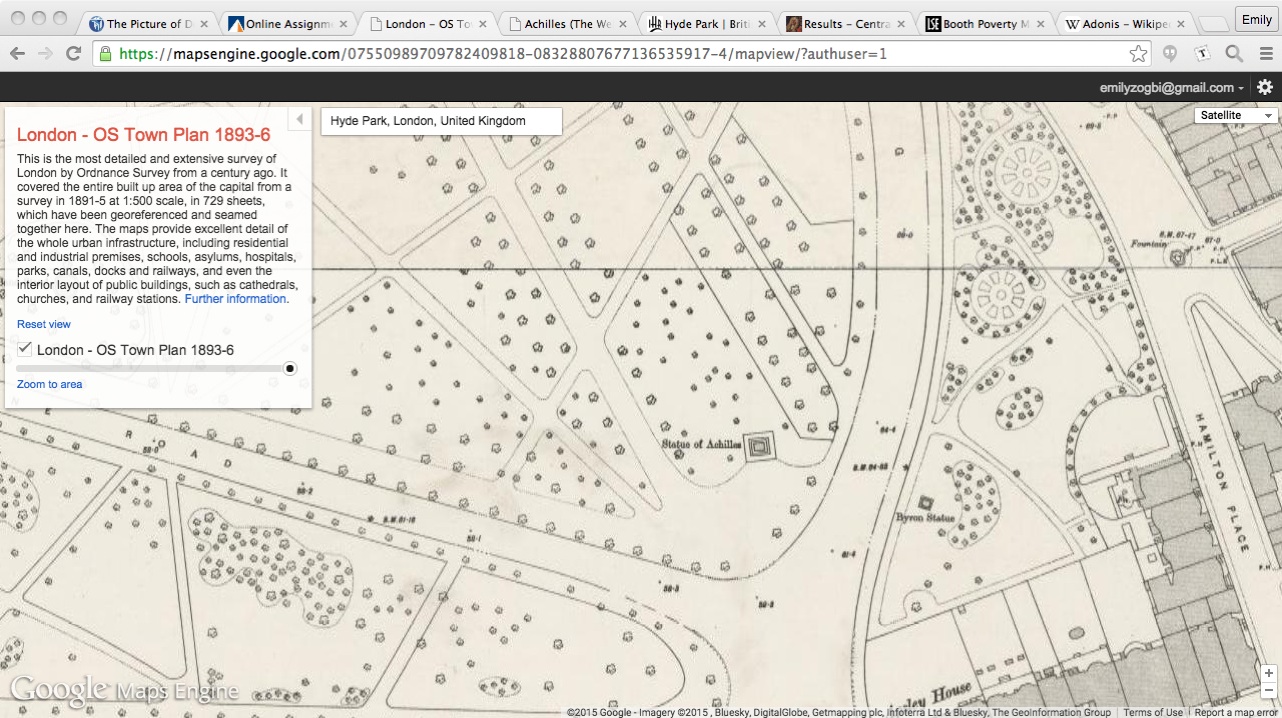

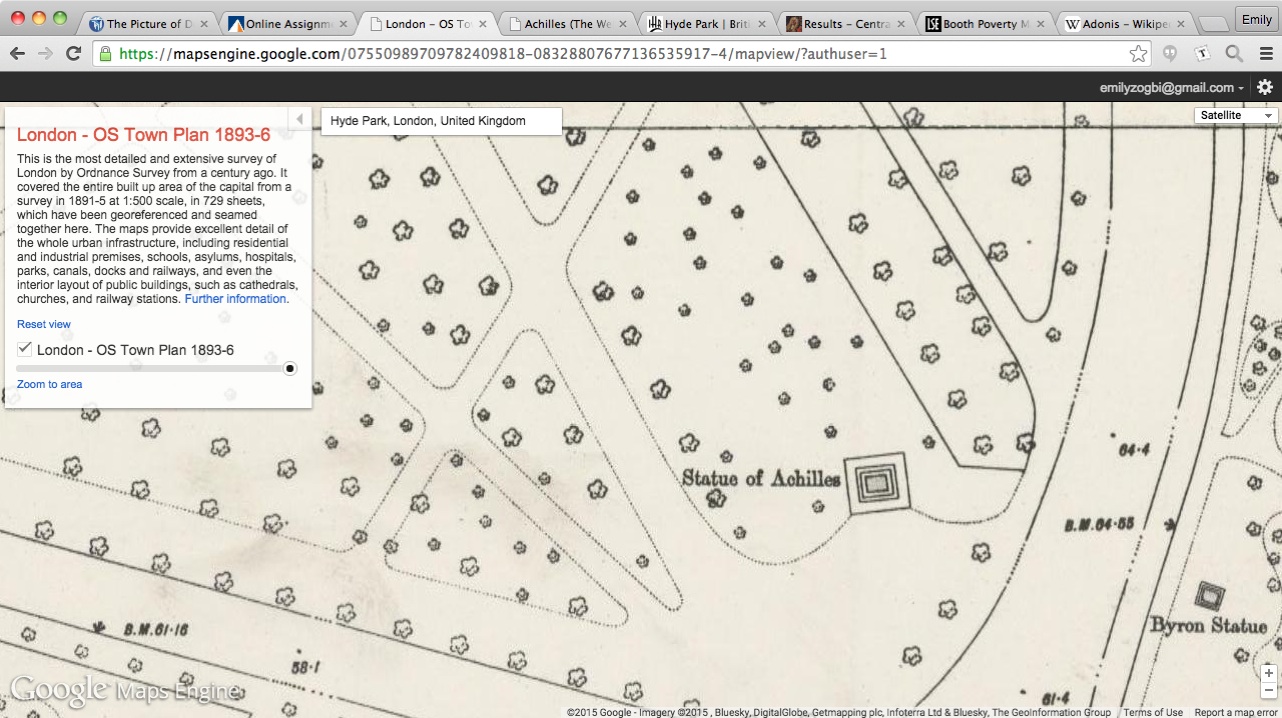

In chapter 5 of Dorian Gray, Sibyl and Jim Vane approach the monument while in the middle of an argument. Jim claims that “as sure as there is a God in heaven, if he ever does you any wrong, I shall kill him” (Wilde). The people around them begin to stare and gape, “a lady standing close to her tittered” (Wilde). The argument continues on until they reach the Achilles Statue. When they fight in front of the statue, it is as if they are fighting in front of Dorian himself. Around all these wealthy people, people concerned entirely with appearance, Sibyl and Jim fighting in public further separates them from this society. They are crossing the public and private, by fighting about private matters in the middle of a public park, and these are two things that should remain entirely separate. Jim is embarrassing Sibyl with the ugliness of his words, because she is in love with Dorian. She immediately tells him, “Come away, Jim; come away” (Wilde) and leads him out of the crowd of people.

This relates to the themes in Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray in many ways. It speaks to this idea of translating people into art (what Basil wishes to do with Dorian) and capturing their beauty forever. The creation of the statue parallels Basil’s creation of Dorian’s portraits, in the sense that the beauty of these figures is being captured and translated into art, which will last forever, eventually outliving the people that inspired the art in the first place (something that perplexes and upsets Dorian). I think it’s easy to say that Dorian wishes to be Adonis, ever-youthful and beautiful, but I think that Dorian really wants to be Achilles, the statue itself. He wishes to be trapped in time, unchanging, unaging. This also relates to the theme of art, specifically the purpose of art, which Wilde addresses directly in this novel. Wilde, and other members of the aestheticism movement, are arguing that art shouldn’t have to serve a purpose, it should just be beautiful. The creation of the statue seemed to have to have been justified as a war monument for it to be able to be displayed, when it could have just been a work of art created solely to be looked on and enjoyed by the public.

Sources:

“Achilles (The Wellington Monument).” The Victorian Web. The Victorian Web, 21 August 2006. Web. 16 December 2015. http://www.victorianweb.org/victorian/sculpture/westmacottr/2.html

Walford, Edward. ‘Hyde Park.’ Old and New London: Volume 4. London: Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1878. 375-405. British History Online. Web. 14 December 2015. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/old-new-london/vol4/pp375405.

Wikisource contributors. “The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891).” Wikisource . Wikisource , 30 Sep. 2015. Web. 16 Dec. 2015.