Daniela Velez

Prof. Swafford

ENG 493-02

Final Project, Location: Selby Royal

“Are they true? Can they be true? When I first heard them, I laughed. I hear them now, and they make me shudder. What about your country-house and the life that is led there? Dorian, you don’t know what is said about you.”

-Basil Hallward to Dorian Gray in Chapter XI, The Picture of Dorian Gray

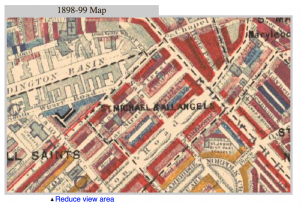

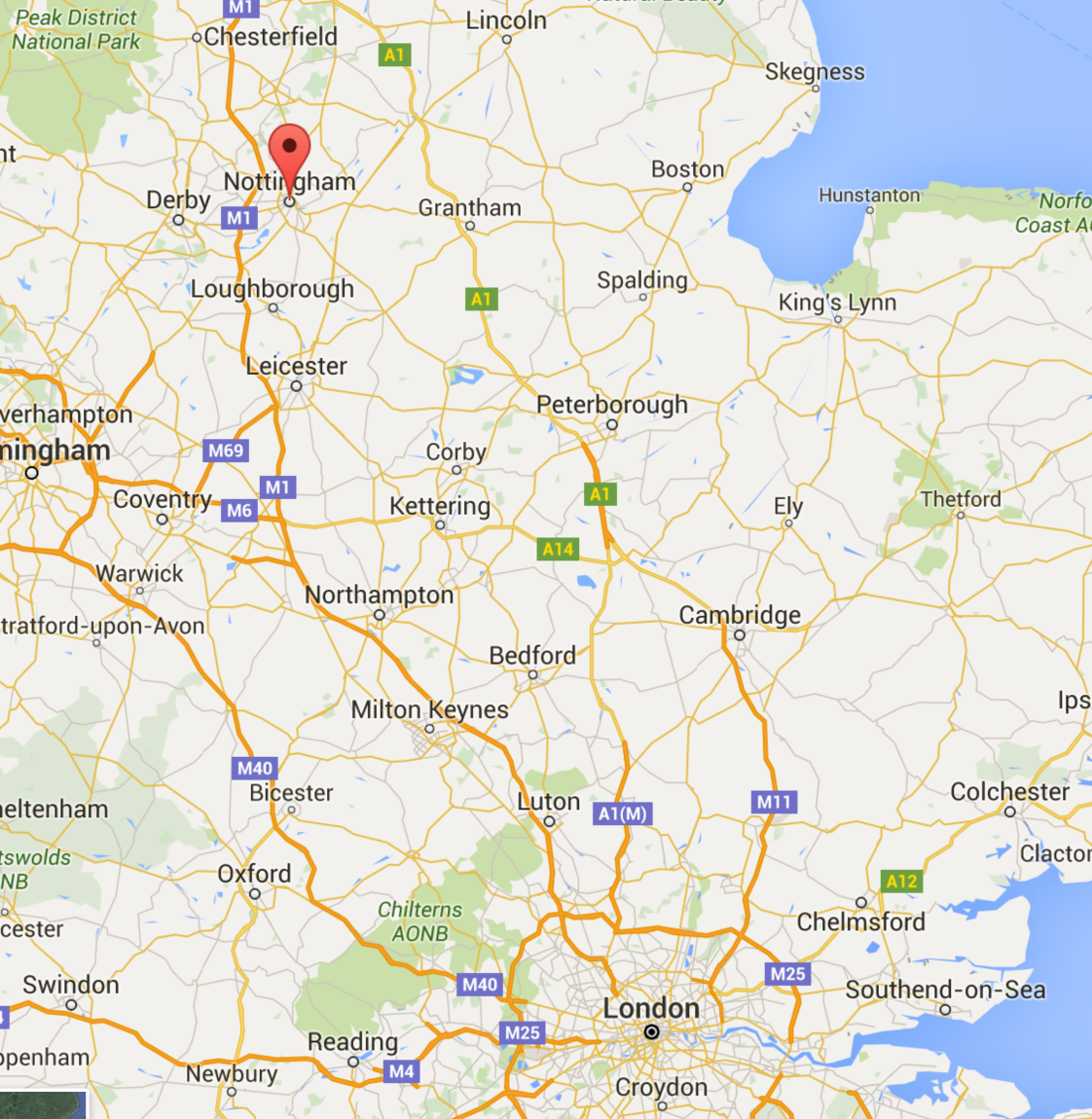

Nottinghamshire – being in the country, not in the city- is excluded from the Charles Booth Online Archive. There is not even a mention of Nottinghamshire in the index of subjects, places, people, and institutions mentioned in the survey. This mirrors the location’s importance in the story. While away in the countryside, the wealthy and the privileged elite are physically far away from the public’s scrutiny but they cannot completely escape it.

Although Basil hears rumors of Dorian’s “country-house and the life that is led there,” there is no evidence of the events that occur, besides Dorian’s somewhat tarnished reputation, which he cares little for. Selby Royal is foreshadowed by Basil’s interrogation of Dorian in the chapter preceding his violent murder and the convenient accidental death that takes place at Selby Royal after it. Before readers see or experience Dorian’s country home, it already has a negative connotation. When James Vane is killed this only solidifies Selby Royal as a location where Dorian lives with little regard to the consequences of his actions.

A week later Dorian Gray was sitting in the conservatory at Selby Royal, talking to the pretty Duchess of Monmouth, who with her husband, a jaded-looking man of sixty, was amongst his guests.

-Chapter XVII, The Picture of Dorian Gray

Accessed through the British History Online Archive, Robert Thoroton’s History of Nottinghamshire documents the parishes and churches in the area. Published in 1796, the source can be considered far removed from the time period in which The Picture of Dorian Gray takes place, but it is still useful in understanding the history the countryside would have been associated with in the minds of Victorian readers. A

majority of the images archived online feature in Thorton’s volumes are images of the numerous churches in Nottinghamshire. As we know from our study of the Victorian Era, religion and piety were of the utmost importance in society, but the images of these churches were captured prior to this time period which began in the early 1800s. As modern readers we can speculate whether or not the religious history of Nottinghamshire had some influence on Wilde’s decision to place Dorian’s fictional country manor there.

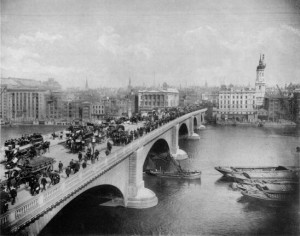

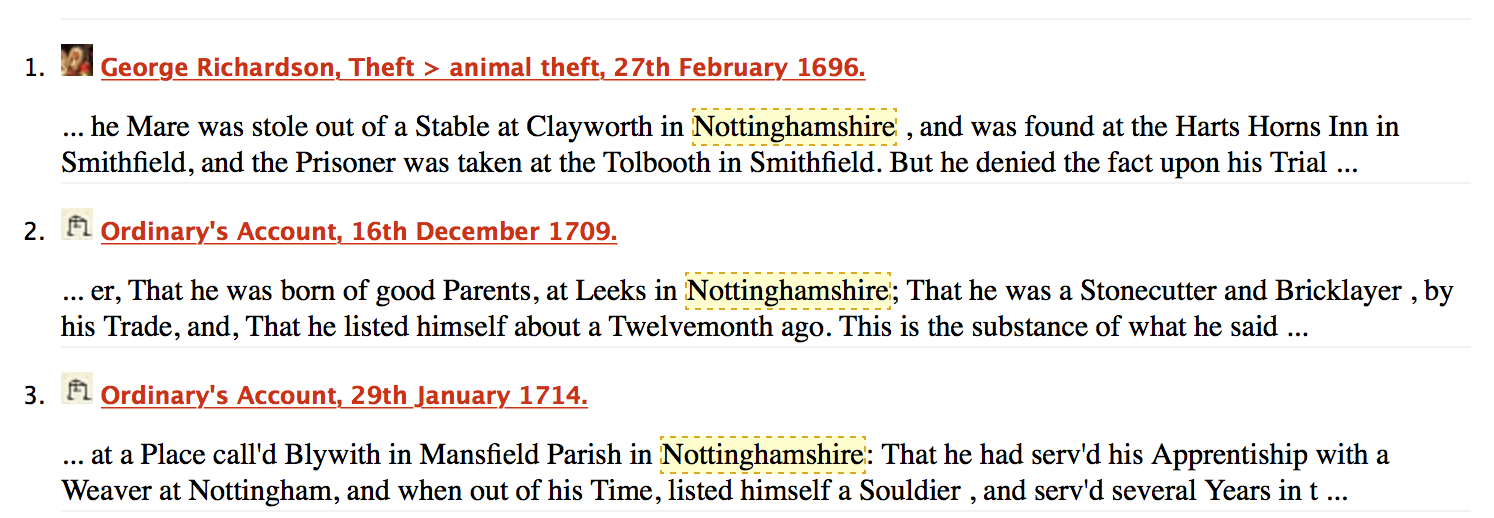

A search of the Proceedings of the Old Bailey turns up only one crime that took place in Nottinghamshire, the theft of a horse. This may remind readers of Dorian Gray riding off on his mare to the stables to see the body of James Vane. Nottinghamshire does come up in other cases a total of twenty nine times but the area is usually mentioned in a positive light. For example, one ordinary’s testimony states “That he was born of good Parents, at Leeks in Nottinghamshire.” Therefore, we can conclude that Nottinghamshire would have been associated with a very peaceful and crime free, almost utopian, country parish. I would compare this to the way many residents of New York City view the Hudson Valley area. By setting up this country home as a topic of gossip and controversy, Wilde is undermining his Victorian audience’s perspective of the area. This gives the impression that danger, crime, and sin are not isolated to a location like the East End. In Wilde’s novel, Selby Royal is both the grand estate associated with the wealthy upper classes and a mansion of improprieties and sins that are implied and spoken about, but never directly addressed.

A search of the Proceedings of the Old Bailey turns up only one crime that took place in Nottinghamshire, the theft of a horse. This may remind readers of Dorian Gray riding off on his mare to the stables to see the body of James Vane. Nottinghamshire does come up in other cases a total of twenty nine times but the area is usually mentioned in a positive light. For example, one ordinary’s testimony states “That he was born of good Parents, at Leeks in Nottinghamshire.” Therefore, we can conclude that Nottinghamshire would have been associated with a very peaceful and crime free, almost utopian, country parish. I would compare this to the way many residents of New York City view the Hudson Valley area. By setting up this country home as a topic of gossip and controversy, Wilde is undermining his Victorian audience’s perspective of the area. This gives the impression that danger, crime, and sin are not isolated to a location like the East End. In Wilde’s novel, Selby Royal is both the grand estate associated with the wealthy upper classes and a mansion of improprieties and sins that are implied and spoken about, but never directly addressed.

Works Cited

“Booth Poverty Map & Modern Map (Charles Booth Online Archive).” Booth Poverty Map & Modern Map (Charles Booth Online Archive). N.p., n.d. Web. 01 Dec. 2015.

“The Proceedings of the Old Bailey.” Results: Nottinghamshire. Old Bailey Online, n.d. Web. 01 Dec.2015.

Robert Thoroton, ‘Plate 3: Views of several churches’, in Thoroton’s History of Nottinghamshire: Volume 1, Republished With Large Additions By John Throsby, ed. John Throsby (Nottingham, 1790), p. 3 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/thoroton-notts/vol1/plate-3 [accessed 1 December 2015].

Wilde, Oscar, and Camille Cauti. The Picture of Dorian Gray. New York: Barnes & Noble Classics, 2004. Print.