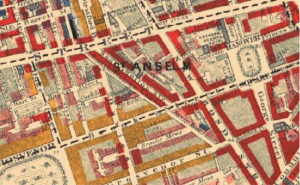

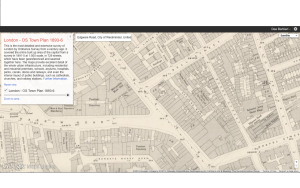

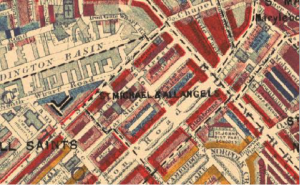

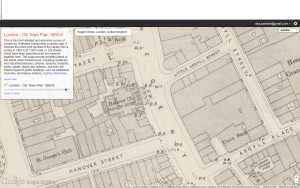

Covent Garden, a market resurrected in 1656, is where Dorian finds himself wandering around after he ends his relationship with Sibyl. At first he walks through unnamed streets that are described as “evil-looking,” “dimly lit” and “grotesque.” The description of these streets is only a few lines, while the description of Covent Garden is almost an entire page, again showing how Dorian doesn’t wish to spend time in places he doesn’t consider beautiful. Covent Garden was known for its flower, fruit, and vegetable market and Dorian arrives there at daybreak, finding an aesthetic comfort in this setting. “The air was heavy with the perfume of flowers, and their beauty seemed to bring him an anodyne for his pain” (93). After all the ugliness that he’s just witnessed with Sibyl’s acting and her reaction to being broken up with, Dorian finds peace in a beautiful place not yet open for business. Dorian finds the market beautiful so he takes his time in it before calling a cab home. Charles Dickens also wrote of Covent Garden in a similarly romantic manner in Martin Chuzzlewit, The Victorian Web including a passage of Ruth and Tom Pinch walking around London. The phrase repeated throughout the passage is “many a pleasant stroll” were taken in the market, and the two characters are described taking in the surrounding market with “the perfume of the fruits and flowers” in the air.

Looking at two major works from this time shows its popularity among writers and how romantic a place it was for Londoners. It was a place of community, a small area of green in an otherwise dark and concrete city. The fact that Dorian goes there alone adds to the gloominess of how he’s feeling about his current situation; he’s all alone in an otherwise bustling part of London, coming to terms with the ugliness of the world. As Charles Dickens, again, wrote in Night Walks, “Covent-garden Market, when it was market morning, was wonderful company.” So perhaps the market was all the company Dorian wanted. Seeing as it was an area of commerce and everyday shopping, much of the crime in or near Covent Garden was theft according to the Old Bailey, although often much less violent thievery than seen on Rupert Street.

Works Cited (Both Locations):

“Booth Poverty Map & Modern Map (Charles Booth Online Archive).” Booth Poverty Map & Modern Map (Charles Booth Online Archive). N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

“The Proceedings of the Old Bailey.” Browse. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

“Covent Garden.” The Dictionary of Victorian London. VictorianWeb.org. Web. Dec. 2015.

“Covent Garden.” Victorian Web. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray. New York: Barnes & Nobles Classics, 2003. Print