The phrase “country club” immediately connotes the utmost pretention and affluence; to the average person, this is the location where men in nine-hundred dollar suits go to play golf and talk about their money in posh accents. While the stereotypes associated with these places are certainly not true for every member, they certainly are for Lord Henry Wotton. He says: “I can sympathise with everything except suffering…I cannot sympathise with that. It is too ugly, too horrible, too distressing” (Chapter 3). His credo is hedonistic at best and a direct result of his wealth; he especially does not sympathize with the suffering of the lower classes because they cannot afford the same self-indulgences and thus, they are deemed ugly. For Lord Henry, the “country club stereotype” holds true—he is, in fact, linked with the Orleans Club in the text. This elite club, based out of Twickenham, provided a town house on King St. (near Covent Garden) for both members as well as a non-members (for a fee).

We are not given any evidence to support whether or not Lord Henry is a member, only that he must “meet a man at the Orleans.” Either way, money is involved. If one was a member of the Twickenham Orleans Club, then the annual fee for the London Orleans Club was £8.8 (not including the £15.15 entrance fee and the £10.10 annual fee necessary for membership to Twickenham). In the year 2000, that roughly translates to £3,042 which, in 2015, is approximately $6,388. If he was not a member of the Twickenham branch but was only a member of the London branch, then he would have to pay the same annual fee of $6,388 plus the cost for each additional visit of $3,992. According to “Golf Digest,” the average cost of American country clubs is $6,245, so it follows that The Orleans Club has very high standards.

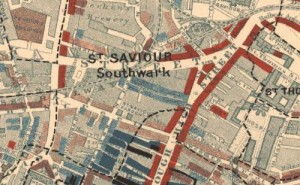

Because of the amount of money that is required to visit the Orleans club, one would imagine that it would be located in a wealthy district. According to the Charles Booth Poverty Map however, if the Orleans Club is located on King St. near Covent Gardens, it is surrounded by predominantly middle-class citizens with few poor districts interspersed throughout.

This inconsistency could mean one of two things: either 1) that it could be located on a different King St. in London or 2) that it would account for the Orleans Club rule that “No person is eligible for admission who is not received in general society.” If the surrounding area was of a lower class, then rules are already in place to keep them out—coinciding completely with Lord Henry’s belief system and the classist disposition of many aristocrats. Either way, wealth is praised and poverty is admonished.

Avery, Brett. “Golf & Money: How To Join A Private Club.” Golf Digest. N.p., 12 Aug. 1012. Web. 17 Dec. 2015.

“Booth Poverty Map & Modern Map (Charles Booth Online Archive).” Booth Poverty Map & Modern Map (Charles Booth Online Archive). N.p., n.d. Web. 16 Dec. 2015.

Gaskins, Robert, and Randall C. Merris. “Calculate Modern Values Of Historic Concertina Prices.” Concertina. N.p., 1 June 2005. Web. 17 Dec. 2015.

“Orleans Club.” The Dictionary of Victorian London. Victorian Web. Web. Dec. 2015.

Wilde, Oscar. “The Picture of Dorian Gray.” Chapter 2.” – Wikisource, the Free Online Library. N.p. 1891. Web. 16 Dec. 2015.