The topic of Taíno language was a decision Matt and I came about after really cutting down on all of our other Ideas.

My interest in the topic was really rooted in y interest in linguistics and how the language of a population has such a big impact on their culture and way of thinking.

Also with my interest in social science, I did tend to gravitate towards the policy aspects of the Taino language in regards to colonization and sovereignty of Puerto Rico.

So for that, I decided to focus on the Movimiento Indígena Jíbaro Boricua (MIJB), the Taíno Nation (TN). Along with the Liga Guakía Taína-Ké (LGTK), which is more focused on the language aspect.

The MIJB community has a website in it which they detail what they are fighting for, which is a representation of the Taíno people and it’s language. It is also tied to TN and most of the information from both of these I got from the website (click the flag!).

Their website is very interesting because it has so many online documents about them linked to it. I didn’t get a chance to read all of them because they have so many different topics, from the census data of the number of Taínos which are still around, descriptions of the flag, prayers for the Taíno ancestors, and Taíno art from different time periods.

The main focus was on the LGTK, which has language rejuvenation programs which teaches students about the language culture and identity. There is a blog post on their website which details what their program does and how it works.

Here is a chart that they shared on their website. Although it is in Spanish here’s a translation of some of it:

The program is meant to offer:

- Workshops and quality classes in public schools and other educational institutions with a focus on the support, and participation of the institution’s directors, teachers, parents, and students all in an effort to give a cultural identity through a multidisciplinary program.

- Fortify the abilities and understandings of parents and students in an effort to strengthen the community to allow for the betterment of the social and cultural knowledge which they share.

They do all of its community building via lessons about their history and knowledge of the Taíno culture.

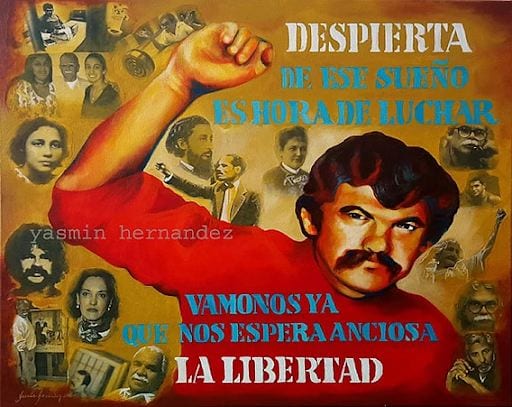

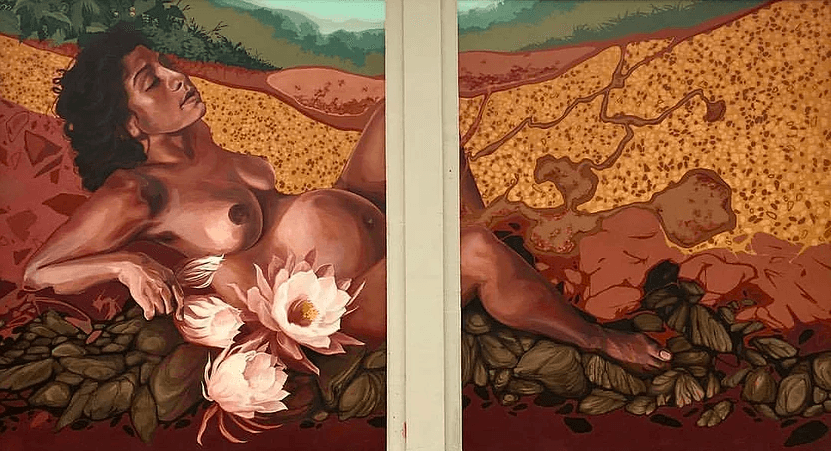

I found that the use of language was a form of resistance to colonization because it rewrote the narrative of colonization by talking about the history that the colonizations erased. This fights that but also rights the Taíno culture back into the history of Puerto Rico and makes their presence known once more. Since they are spoken to as an “extinct” culture, speaking and teaching the language along with the culture counteract the colonialism. The language can be used to restore the identities of the Taínos and give them the power which they need to assert their importance on the archipelago. Language, in a sense, is a form of magic giving back power to the cultures that use it as a form of resistance against the colonial imposition.

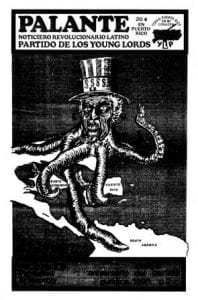

One thing that I did think about a lot during my research was which colonizers are those who practice the Taíno language resisting? would it be the U.S. imperialism/ Colonization, or would it have been the previous Spanish colonization? And if it is the U.S’s imperialism which is being resisted what other forms of decolonization along with resistance tot he imperial language can help completely push back that colonization? What forms of resistance will be the most effective in transitioning the wealth of power back to Puertoricans and Taíno descendants?

Link to the Presentation: Look at me!!

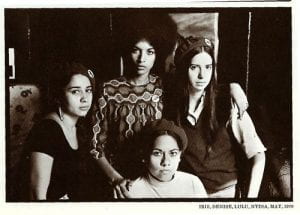

Lady Lords.

Lady Lords.