My first exposure to the philosophical side of 3D printing was Fabricated by Hod Lipson and Melba Kurman. It was an excellent introduction to the field in 2013, and still is. This was where I first encountered the idea of being able to distribute manufacturing across many sites, which was described as Cloud Manufacturing. I tend to prefer the term “distributed manufacturing”. I don’t like “cloud storage” either, it makes it all sound so ethereal when it really is physical servers in an anonymous– looking warehouse somewhere. Anyway, the idea is that anyone with a 3D printer can manufacture something. If you have 5,000 people with printers connected through the internet, they can manufacture a lot of parts. This was done world–wide at the beginning of the pandemic to manufacture PPE. The HVAMC was enthusiastic to participate with our 40+ printers as well as coordinate the design and logistics for a large group of public-spirited companies, schools, libraries and many people with their own home printers. They are all listed here: https://www.newpaltz.edu/hvamc/covid19faceshields/

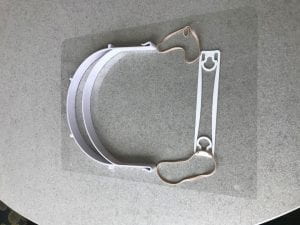

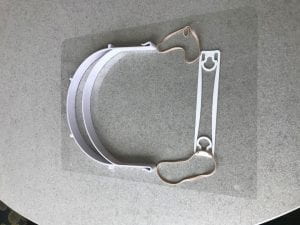

Everything you need to assemble a HVAMC Face Shield

I’m not going to repeat the details, as my colleague Aaron Nelson did an excellent job describing what happened at New Paltz here: (https://sites.newpaltz.edu/news/2020/10/aaron-nelson-academic-minute/). However, I think it’s worth reflecting on why this is probably the only really good example of distributed manufacturing in the 10 years or so since affordable desktop 3D printers became available.

First, face shields are easy to make. I was honestly surprised that we really did run into a shortage since there are many industries that could easily retool to make them (and did), but the suddenness of the pandemic, the generational decrease in manufacturing capacity and the lack of national leadership all combined for a perfect storm. Second, the only parts needed for our design, other than 3D printed parts,

New Paltz undergraduate Rachel Eisgruber with LOTS of face shields.

were rubber bands and overhead transparencies so we were able to work around material shortages. Third, desperation on the part of medical and civic authorities. Our face shields were eventually cleared by infection control at a large regional hospital chain, but it was fairly clear that they would prefer getting a standard face shield from their normal suppliers. Fourth, several organizations stepped up to coordinate design and distribution as we did in the Mid-Hudson Valley. I want to give credit to Stratasys‘ role at the national level in providing designs, free material and, most importantly for us, assurance that we weren’t breaking any FDA regulations!

The story also points out the limitations of distributed manufacturing with 3D printers. With

everyone we know in our region going all–out printing face shields, we only shipped about 8000 and it was clear the demand was outstripping the supply. Our fleet of Makerbots were also in pretty bad shape by the time we were done. Fortunately, we started making plans early to scale up. This required from help from traditional manufacturers and local companies IBM, USHECO and M-Tech Design stepped up big time and machined two different molds and started making parts by injection molding within 3 weeks. Our role then became much more about logistics and shipping in order to deliver 25,000 face shields within six weeks.

Th COVID emergency also pointed out where distributed manufacturing doesn’t work. Face shields were not the only PPE that could be printed, and we kept an eye out for anything that could be useful. A replacement for an N95 mask was the biggest need. There were many designs, with the best I saw being a mask with a replace

Kat Wilson (HVAMC), Dan Young (M-Tec) and Wayne Scheaffer (USHECO) with injection molded face shield parts

able filter made from N95 material. We printed a few samples for local hospitals, but there wasn’t much interest because they were having a hard time getting an appropriate fit or had concerns about sanitizing the material. We also got a lot of requests/interest in printing parts to split a ventilator between multiple patients or even to make a DIY ventilator. Fortunately, the situation never became desperate enough for these highly experimental and risky options.

It was truly exciting to participate in the first effective experiment in distributed manufacturing and it was wonderful to see the variety of folks who were able and willing to dedicate their time and 3D printers. In terms of distributed manufacturing, this crisis showed that under a particular set of conditions it can work but I don’t think we’re going to be using this approach to make aerospace or refrigerator parts anytime soon.

Keep On Printing!

Dan

rly every industry as well as within the maker community, which raises the question: what do we do with all that plastic waste?

rly every industry as well as within the maker community, which raises the question: what do we do with all that plastic waste?