Major Project 1

Angelo Fardella

Cultural Essay: Europe’s Explosive Revolution

April 4, 2023

Constantinople, May 29th, 1453. The fall of the Byzantine Empire. Thought to be impenetrable by land and sea due to its strategic location, Constantinople was a formidable city to conquer. The Ottoman’s laid siege to the capital for nearly two months. While blockades and naval warfare were effective to an extent, they were unable to deal the killing blow. It took a new technology from the East to strike the final blow and conquer this fortuitous city: gunpowder.

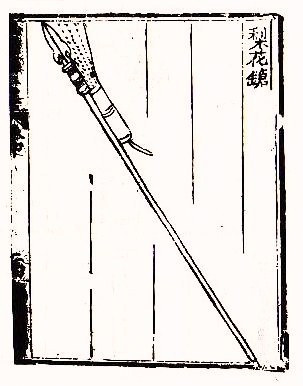

Gunpowder is a fine black powder consisting of saltpeter, sulfur, and charcoal, that was created in China and is used in my forms of weaponry and explosives. Gunpowder was originally developed as an elixir for eternal life by Chinese alchemists, but they found out the hard way just how volatile this compound was. During the 10th and 11th centuries, the Chinese implemented explosives into their army to fend of the invading Mongols. This led to the creation of inventions that would become modern day flamethrowers, firearms, cannons, and grenades. In the academic journal, Science and Its Times, author Dean Swinford writes “the cannons, flamethrowers, and grenades that they used in battle were quickly adopted by European forces for battles on land and at sea. However, Europeans refined the applications of gunpowder and improved the devices that used gunpowder, producing weapons that dramatically transformed the nature of warfare” (343). This refinement for the Europeans would have drastic consequences on the status quo in Europe. Traditions, social status, and military strategies would all be overhauled, changing all aspects of Medieval European life. By analyzing the implementation of gunpowder in Europe during the Late Middle Ages, one can deduce that gunpowder led to changes in military architecture and the decline of knighthood and feudalism, which is important because this revolutionized the ways in which wars would be fought in Europe thereafter.

Figure 1. Chinese Fire Lance

To address the cultural significance of gunpowder, I first draw upon Clifford J. Rogers’ “The Military Revolutions of the Hundred Years’ War” to address feudalism, why it was important, what led to its downfall, and how that led to the rise of a centralized state. Secondly, I utilize François Velde’s “Knighthood and Chivalry” to present knights, the chivalric code of honor, and their role in Medieval Europe’s feudalistic society before the advent of gunpowder. Then, I go back to Rogers’ research to showcase the change from knights to mercenaries and demonstrate how gunpowder made knights militarily obsolete. Next, I breakdown Dean Swinford’s “The Chinese Invention of Gunpowder, Explosives, and Artillery, and Their Impact on European Warfare” to demonstrate gunpowder’s impact on siege warfare. Afterwards, I pull information from Kelly DeVries’ “Gunpowder Weaponry and the Rise of the Early Modern State” to show the implementation of gunpowder weaponry Europe using France as an example. Finally, I conclude my argument by implementing Matthew F. Bailey’s argument into my own. I use Bailey’s “The Early Effects of Gunpowder on Fortress Design” to show the impact gunpowder weaponry had on the construction of castles and fortresses. Thus, I showcase how the advent of gunpowder caused the decline of traditional European society, leaving knights and feudalism behind and heralded the adoption of mercenaries, restructured castles, and centralized states, which would remain in Europe for centuries.

Feudalism was a social and economic system primarily implemented in Medieval Europe, in which royalty owned land was given to nobles who were required to provided military assistance when needed and oversee the peasants who worked the land. Lords were expected to pay taxes and provide military units called knights to the Crown. This resulted in a decentralized state where local lords weren’t under direct control of the Crown and could implement their own laws and taxes on their land if it didn’t go against the Crown. This would last until the Late Middle Ages with the emergence of gunpowder. As the use of gunpowder-powered artillery weapons rose so did the cost of maintaining a military. Central governments were spending double on artillery than other munitions such as bows, lances, and arrows; to afford these new gunpowder armies, governments looked towards their smaller and weaker neighbors. With their more technologically advanced and more numerous armies, bigger governments captured their smaller, weaker neighbors, including independent regions and the nobility that previously held their land (Rogers 272-273). This would mark the end of feudalism in many European countries such as Burgundy and France and would welcome the rise of a centralized state. This allowed for the central government to gain more control over their subjects, made it easier to collect taxes, and centralized the army under one leader rather than many smaller ones. Furthermore, with the end of feudalism came the fall of their primary military unit which had become ingrained in their society: the knights.

Knights were a very important part of the European feudal system. Knights provided protection, stability, and honor to a feudal lord’s land. The Crown required every feudal lord to provide their own personal knights when called upon. Knights consisted of free men (often nobles) who were entitled to provide military service to their lord and worked their entire life to become a knight to fulfill this entitlement. In the early stages of feudalism, the line between knight and noble was blurred but slowly merged around the 13th century. Therefore, knighthood had an important role in feudal society; eventually leading to princes and kings seeking knighthood (Velde). The prestigiousness and success of the knights showcase its importance within Medieval European society. Their military victories and code of honor lead to them becoming powerful and reliable combat units. However, the time would come to an end with the fall of feudalism and the introduction of new military technologies.

European battlefields were dominated by knight cavalry units [see Figure 2] until gunpowder weaponry was introduced to warfare. Knights were units that were known for mounted combat and cavalry rushes to break through the front lines of their enemies However, knights would soon be replaced by infantryman called mercenaries [see Figure 3]. Rogers compares these two units to explain the impact of gunpowder weaponry on military when he writes: “A common infantryman could be equipped for much less than a man-at-arms; he was paid less; he could be trained more quickly; and the ranks of the infantry could be filled from a much broader section of the population” (251-252). Rogers provides conclusive evidence for the downfall of knights. This change in units would drastically change the way any future war would be fought by promoting a style of warfare that laid heavy emphasis on quantity over quality.

Figure 2. Heavy Cavalry Knight

Figure 3. 16th Century Mercenary

Military warfare changed more than just infantry units. Siege weapons and their implementation drastically changed from the advent of gunpowder. Before gunpowder, Siege warfare was extremely long and arduous, often taking months or years of blockades and negotiation. Then, cannons [see Figure 4] were introduced to Europe’s arsenal; sieges only took weeks to months since the cannon allowed for a more consistent and dangerous way to attack a fortress without losing a whole army. In Swinford’s opinion, gunpowder weaponry redefined the typical view of medieval siege warfare: “siege artillery that used gunpowder replaced siege engines, such as the catapult, which was characteristic of medieval warfare” (344). Gunpowder powered siege artillery brought about a new standard in medieval warfare. With the change in military weaponry comes the change in military tactics and strategy. After gunpowder, many militaries were forced to implement these new weapons into their ranks lest they wanted their opponent to have an upper hand on the battlefield.

Figure 4. Medieval Cannon

A great implementation of gunpowder into the military is seen in France during the Hundred Years’ War. During the 14th century the French royal army had little to no gunpowder technology; any gunpowder weaponry used by the French army was borrowed from local militias. French kings were unwilling to acquire gunpowder weaponry and relied on local lords for manpower. This all changed with King Charles VII when he took the throne in the 15th century. In preparation for the next period of the Hundred Years’ War, Charles VII instituted a program that called for the acquisition of gunpowder weaponry and the restructuring of the French royal army to accommodate gunpowder artillery. DeVries goes into detail about these changes when she writes: “Duties of cannoneers were established, officers were appointed, competence was improved, and pay was increased. This allowed Charles’s military leaders to take his artillery on every military expedition — which led to numerous victories” (132). King Charles VII’s victories during the Hundred Years’ War demonstrates the effectiveness of gunpowder. Although army formation is a large part of warfare, tactics and strategy hold an equally important role.

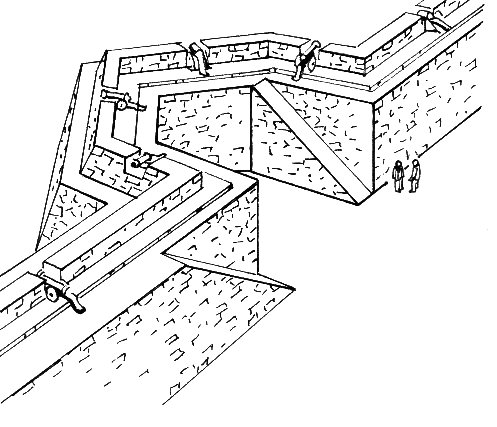

Castle or fortress require a great deal of thought when they are planned out. Architects must consider what tactics the enemy might employ and how these tactic can be thwarted by the castle. This was even more true when gunpowder weaponry started to be implemented. Gunpowder weaponry made it so that the offense had an advantage in relation to siege warfare; castles were easier to take, and their defenses suffered. This inequity of strategy led medieval architects to develop two castle enhancements: the artillery tower [see Figure 6] and the bastion [see Figure 5]. The artillery tower focused on defense and was “a strongpoint, in order to house gunpowder weapons, was usually tall and multi-tiered, with an open top for the largest guns” (Bailey 84). The artillery tower provided the defense with a vantage point that would let it rain artillery on the more distant units. Bailey states “to be a bastion, a structure must jut outwards from the fortress, and must house hidden, thickly defended flanking artillery aiming down the wall, so as to provide supporting fire to a neighboring position” (84-85). Bastions focused more on the offensive part of the castle, as it allowed for the defenders to consistently rain artillery on closer attackers who were near the wall of the castle. Both forms became quite popular and would remain for centuries.

Figure 5. Medieval Bastion

Figure 6. Medieval Artillery Tower

The weight of the evidence suggests that the introduction of gunpowder into Medieval Europe had drastic changes in military warfare as well as the political and social climate. The decline of feudalism gave way to the rise of a centralized state. In this state, the Crown was given immense power, more power than it has ever had before. This led to changes in tax structure and military structure, all of which were controlled by the king rather than local lords. Additionally, the decline of knighthood allowed peasants and lower-class men to enlist in the military. The quick training synonymous with mercenaries allowed for anybody to become a soldier and didn’t require a lifetime of training and discipline associated with knights. Finally, the change in military architecture supported defense research and restructuring efforts in a period where the offense had the advantage. Although gunpowder has had a lasting impact on Medieval Europe, what is its impact on contemporary society? Gunpowder remains prevalent in modern-day warfare, being used in all different kinds of bullets and weaponry. Has gunpowder created a society dominated by guns and violence? Or are these new developments of gunpowder we see today used purely as forms of protection and self-defense?

Works Cited

Bailey, Matthew F. “The Early Effects of Gunpowder on Fortress Design: A Lasting Impact.” Vexillum, no. 3, 2013, pp. 75-94. http://www.vexillumjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Vexillum-3-2013.pdf

DeVries, Kelly. “Gunpowder Weaponry and the Rise of the Early Modern State.” War in History, vol. 5, no. 2, 1998, pp. 127–45. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26004330. Accessed 21 Mar. 2023.

Rogers, Clifford J. “The Military Revolutions of the Hundred Years’ War.” The Journal of Military History, vol. 57, no. 2, 1993, pp. 241–78. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2944058. Accessed 26 Mar. 2023.

Swinford, Dean. “The Chinese Invention of Gunpowder, Explosives, and Artillery and Their Impact on European Warfare.” Science and Its Times, edited by Neil Schlager and Josh Lauer, vol. 2: 700 to 1449, Gale, 2001, pp. 342-345. Gale eBooks, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3408500882/GVRL?u=newpaltz&sid=bookmark-GVRL&xid=11e2ebf8. Accessed 26 Mar. 20

Velde, François. “Knighthood and Chivalry.” Heraldica, Sept. 1996, https://www.heraldica.org/topics/orders/knights.htm.