Major Project 2

Curatorial Statement

It often seems that in contemporary society there is no authority without power. Power can be obtained in many ways but it seems the most successful way is through the acquisition and development of weaponry. The most common weapons in today’s society are guns. Firearms have been around for a very long time, dating back to the 10th century. The journey from the creation of gunpowder to the modern form of gunpowder used today is an interesting one that spans around a thousand years. This journey is known as the Gunpowder Age. This exhibit starts with black gunpowder as seen in the Chinese military compendium, Wujing Zongyao from authors Zeng Gongliang (曾公亮), Ding Du (丁度) and Yang Weide (楊惟德) from 1040 AD to 1044 AD. In this compendium the authors give the formula for black gunpowder that would be utilized for hundreds of years. The exhibition finishes with the creation of smokeless powder which is considered to be the successor to black gunpowder. An advertisement from Hercules Red Dot Smokeless Powder is shown to signify the jump to the modern era. Within a thousand years, a small fraction of our time on Earth, humans were able to develop a technology so much that it made other technologies obsolete. This ranges from melee weapons such as swords, clubs, and axes to ranged weapons, like slings, arrows, and lances. This exhibition invites the audience to consider the impact gunpowder has had not just on warfare but culture and society. Are the killings caused by this weaponry justifiable? How has it molded the idea of power as we see it today? Has the mass implementation of these weapons made us desensitized to the lives that they take? By the end, this exhibition leaves the audience with an ad to show the selling of war and leaves the audience wondering if this sale is justified or necessary.

Black Gunpowder (circa 9th Century AD)

“Wujing Zongyao”, a military compendium by Ding Du, Zeng Gongliang, and Yang Weide, created in 1044 AD.

We start our tour of the evolution of gunpowder with the item itself. Gunpowder is a fine, black, powder consisting of saltpeter, sulfur and charcoal as detailed in the Wujing Zongyao. The exact time gunpowder was created is unknown due to it being so old but it is estimated to be created around the 9th century AD in China but was written in the Wujing Zongyao in 1044 AD. Gunpowder was originally developed as an elixir for eternal life by Chinese alchemists but its volatility was discovered soon after its creation leading to its development as a component of war. The discovery of gunpowder would signal the beginning of the Gunpowder Age.

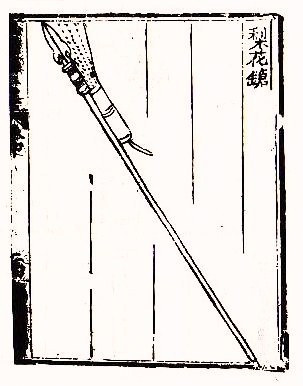

Chinese Fire Lance (circa 950 AD)

“Huolongjing”, a military treatise by Jiao Yu and Liu Bowen, created during the 14th century.

One of the first gunpowder inventions created by the Chinese was the fire lance. The fire lance was created around 950 AD and works by attaching a firework-like charge to the end of a spear. It appeared in the Huolongjing during the 14th century. Fire lances would shoot out flames as well as other small projectiles. This makes the fire lance the predecessor to both the flame thrower and the firearm. The fire lance would be used by the Song Dynasty in China against the invading Mongols. The Mongol’s victory over the Song Dynasty led to the expansion of gunpowder and gunpowder technology to Europe, the Middle East, and India.

Mongol Invasion of Japan as Seen in the Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba (1274 AD)

“Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba pgs. 3-5” commissioned by Takezaki Suenaga from an unkown artist, 1293 AD.

The Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba or the Illustrated Accounts of the Mongol Invasion is a set of Japanese handscrolls (emaki) commissioned by samurai Takezaki Suenaga in 1293 AD; however the author and artist commissioned by Suenaga are unknown.. The scrolls depict the invasion of Japan that was conducted by the Mongols in the years 1274 and 1281. For the sake of this tour the first scroll is what is more important. A part of the first scroll depicts Mongol archers (left) using fire arrows acquired by the Song dynasty against Japanese samurai (right). The highlight of the scene is the implementation and use of early gunpowder technologies in battle.

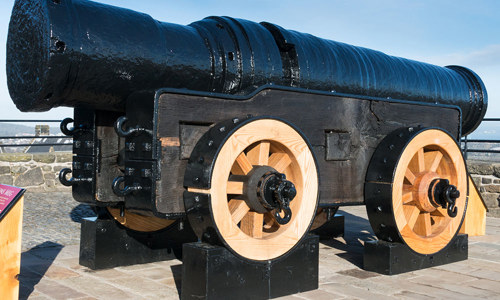

Mons Meg (1449 AD)

“View of Mons Meg, refurbished in 2015” <https://www.edinburghcastle.scot/see-and-do/highlights/mons-meg>

While gunpowder may have started in China, it would be greatly expanded upon in Europe. One great example of this is the Mons Meg. The Mons Meg is a heavy artillery cannon constructed under the order of the Duke of Burgundy in 1449. It was later given to King James II of Scotland in 1457 as a gift. The Mons Meg’s barrel has a diameter of 20 inches or 510 millimeters; this makes it one of the biggest artillery cannons in the world. The Mons Meg was used in many battles across the United Kingdom and on sea under the reigns of King James II, King James IV, and King James V.

Matchlock Device (1475 AD)

“Matchlock Musket, circa 1580” unknown manufacturer, circa 1580, The Henry Ford Museum.

The matchlock is a device that was developed in Europe which is used to ignite the gunpowder in the gun, allowing it to fire. The device works by having an arm that holds a match called a serpentine descend when the trigger was pulled causing the gunpowder to ignite. The matchlock was a major advancement in small arms manufacturing because it allowed the user to fire the gun with the pull of a trigger, whereas before the matchlock the user had to manually ignite the gunpowder with a match. This makes firing more accurate and efficient.

True Flintlock Device (1680 AD)

“Braddock Pistol” manufactured by Gabbitas, circa 1750, National Museum of American History.

The matchlock ignition system would soon be replaced by the flintlock ignition system, which was developed by French gunsmith Marin le Bourgeoys in 1550. This device worked by using a piece of flint that would strike sparks in a iron pan filled with gunpowder. Unlike matchlocks, flintlocks were able to fire in wet conditions since it does not use an open flame. Flintlocks would be added to many weapons such as the musket and the arquebus.

Metallic Cartridge (1812 AD)

“Cartridge Case”, bequest of George C. Stone, 18th-19th century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As we step closer to the modern day, we start to see technologies that closely resemble the ones in our contemporary society. This starts with the metallic cartridge or bullet. The design for the first metallic cartridge with a primer in it already was Jean Samuel Pauly. The primer is what propels the projectile being fired. Pauly created an all-in-one ammunition which meant that no fuses or flint was needed to fire the weapon. This allowed for bullets to be entered through a breech rather than through the barrel of the gun.

Henry Repeating Rifle (1860 AD)

“Henry Rifle”, manufactured by New Haven Arms Company, circa 1860, National Museum of American History.

The Henry Repeating Rifle was invented by Benjamin Tyler Henry in 1860 and used the new ammo created by Jean Samuel Pauly. This was the first reliable repeating rifle, meaning that it could insert cartridges quickly through a breach and keep firing with little delay. Furthermore, the Henry Rifle was capable of holding multiple cartridges at once which means that it could fire consistently. It saw heavy use during the Civil War.

Maxim Machine Gun (1884 AD)

“British Maxim .303, Converted MK 2 machinegun”, manufactured by Enfield, 1892, Imperial War Museum.

The maxim gun was created in 1884 by American-British inventor Hiram Maxim. The Maxim machine gun serves as the predecessor to the modern machine gun and is the first fully-automatic weapon. The gun had a bandolier of bullets fed into it that allowed for continuous fire for a prolonged period of time. The Maxim gun would implemented by most countries throughout the late 19th centuries as they searched for colonies.

Smokeless Powder (1886 AD)

“Advertisement for Hercules Red Dot Smokeless Powder”, an advertisement created by Hercules Incorporated, 1945.

Smokeless powder was developed in 1886 by French scientist Paul Vieille. Smokeless powder is made of nitrocellulose, nitroglycerin, and sometimes nitroguanidine. The reason that smokeless powder is considered to be superior to black powder is because it is three times as powerful as black powder, can be burned when wet, and (as the name suggests) doesn’t produce smoke, which allows the user to see when firing multiple shots and doesn’t give away the position of snipers. The invention of smokeless powder marks the beginning of the end of black gunpowder and the Gunpowder Age.

Works Cited

Braddock Pistol, Washington D,C,, National Museum of American History, owned by George Washington, manufactured by Gabbitas, <https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_746133>.

Cartridge Case, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, <https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/30098>.

Du D, Gongliang Z, Weide Y, 1044, The Formula for Gunpowder, digital image of military compendium, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wujing_Zongyao#/media/File:Chinese_Gunpowder_Formula.JPG>.

Henry, Benjamin Tyler, Henry Rifle Model 1860,.44 caliber, Washington D,C,, National Museum of American History, manufactured by New Haven Arms Company, <https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_414668>.

Hercules Incorporated. “Advertisement for Hercules Red Dot Smokeless Powder.” 1945 Hercules Advertisements, 1945. Records of Hercules Incorporated, Volume 1945. Science History Institute. Philadelphia. <https://digital.sciencehistory.org/works/gq67jr986>.

Matchlock Musket, circa 1580, Missouri, The Henry Ford, <https://www.thehenryford.org/collections-and-research/digital-collections/artifact/50458>.

Maxim Hiram, British Maxim .303, Converted Mk 2 machinegun, Imperial War Museums, manufactured by Enfield, <https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30034916>.

Mongol Forces Shooting Fire Arrows at Samurai Suenaga Takezaki, 1293, scroll, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:M%C5%8Dko_Sh%C5%ABrai_Ekotoba_Mongol_Invasion_Takezaki_Suenaga_2_Page_5-7.jpg>.

Mons Meg from Edinburgh Castle, digital photograph, Scottish Tourist Board, <https://www.edinburghcastle.scot/see-and-do/highlights/mons-meg>.

Yu J and Bowen L circa 14th century, Chinese fire lance as seen in the Huolongjing, digital image of military treatise, <https://dbpedia.org/page/Fire_lance#>.